Introduction

In the first scene of the novel, The Picture of Dorian Gray (1891), the painter Basil Hallward confesses to his friend Lord Henry Wotton why he cannot exhibit the portrait of the eponymous hero. Basil admits, ‘Where there is merely love, they would see something evil, where there is spectacular passion, they would suggest something vile’ (Wilde, 1889–90: 21). This striking line, among many others that carry homoerotic innuendos, never appears in print. It is excised during Oscar Wilde’s revision process, along with other suggestions of homoeroticism between the three main characters of the story. The textual scholarship on this revision process generally agrees that Wilde neutralizes this homoeroticism by transforming Dorian from an erotic object into an aesthetic object. In particular, Nicolas Ruddick argues that Wilde aestheticizes Dorian in order to emphasize a moral about the dangers of vanity at the expense of another, more covert moral about the liberalization of homosexuality. Ruddick explains that, while the moral about vanity ‘dramatize[s] the disastrous consequences of the preference of the beautiful at the expense of the good’, the other moral about homosexuality ‘explores the destructive effects of the clandestine or closeted life’ (Ruddick, 2003: 126, 128). According to Ruddick, the novel’s famous portrait indexes the convergence of the two morals: ‘the appalling changes to Dorian’s painted image … strongly suggest that the unspeakable practices indulged in by the protagonist are unspeakable in themselves’ (129).

To interrogate Wilde’s treatment of the homoerotic elements, this paper examines his revisions across the first chapter of the manuscript of The Picture of Dorian Gray (1889–90). I use an electronic editing tool called the Text Encoding Initiative (TEI, explained further below) to register and describe Wilde’s revisions. My project uses the TEI ‘markup’ not only to examine the nature of Wilde’s revisions, but also the potential for technological tools to engage queerness in textual data. In doing so, it endeavors to answer a question that provokes the emerging field of Queer Digital Humanities, or Queer DH. As literary and electronic textual scholar Julia Flanders asks: ‘do we need to queer markup, or is markup already queerable?’ (2017). Flanders’s question considers the TEI’s place between two current approaches in Queer DH: the first approach wants to disrupt formal systems by imagining alternative ones, and the second, by contrast, maintains that queerness is built into computing and is inherent in computational logic. The first approach consists of speculative or critical making projects that problematize the constructed nature of technical objects. For example, Zach Blas and micha cárdenas propose a speculative codebase that disrupts the expected functionality of computational programs. This project, transCoder, describes hypothetical computer programs such as the ‘destabilizationLoop’, which ‘breaks apart any process that acts as a continuously iterating power’ and ‘nonteleo()’, which ‘strips any program of a goal-oriented result’ (Blas and cárdenas: 2007–2012). Another project that probes the possibilities of queering digital tools is ‘Queer OS: A User’s Manual’, which describes how various components of an operating system might function within an ethos of queerness. For example, ‘Queer OS’ reconceives how a digital interface ‘might seek out self-modification as its ontological premise… transform[ing] both the user and the system’ (Barnett et al., 2016). Such work imagines technological systems and projects that ‘[do] not yet exist and may never come to exist [… do] not yet function and may never function’ (Barnett et al., 2016). The other side of the debate explores how current technological systems and tools already contain elements that encourage queer modes of analysis. For example, work by Jacob Gaboury explores how the ‘NULL value’ in computation signals a ‘refusal to cohere, to become legible’ as a built-in option in computational systems. Gaboury explains how the NULL value ‘corresponds with the epistemological condition of queerness as an excessive illegibility collapsed into an unwieldy frame, an aberrant third-ness within an otherwise normative system of relations’ (Gaboury, 2018). In another project, ‘The Queer History of Computing’, Gaboury exposes and interrogates the ways in which technology creates opportunities for resisting conscription within its systems. Gaboury asserts that ‘there exists a structuring logic to computational systems that, while nearly totalizing, does not account for all forms of knowledge, which excludes certain acts, behaviors, and modes of being’ (Gaboury, 2013: para. 13). According to Gaboury, it is from within this structuring logic that queerness finds the space to operate.

In an attempt to cut between these debates, this project first searches for a structural constraint within the TEI format, and then works through this constraint to analyze the homoerotic elements in Wilde’s manuscript revisions. As such, this project aligns with another that uses the TEI to destabilize our current understanding of Wilde’s textual and historical legacy. Jason A. Boyd’s Texting Wilde Project uses the TEI to mark up the biographical information, particularly references to persons, places, and events, in writings about Wilde’s life. Its goal is to reveal the historical discrepencies and inaccuracies across Wilde’s biography. Boyd points out that ‘Our knowledge of “Oscar Wilde” is not comprised of a corpus of pure and simple facts that allows us an unmediated apprehension of a real person separated from us by only time, but rather this knowledge is comprised of a densely complex and often contradictory accretion of texts’ (Boyd, 2014: para. 1).

Similar to Boyd, my project also uses the TEI to complicate the understanding of Wilde’s textual legacy. It identifies one major constraint of the TEI: that it works best with data that is discrete, rather than smooth data, like the homoeroticism obscured by Wilde’s pen. Here, I apply the rigid constraint of the TEI data structure towards marking up and analyzing this text’s homoeroticism, which I group into the general themes of ‘intimacy’, ‘beauty’, ‘passion’, and ‘fatality’, as well as the pen strokes that Wilde uses to strike these elements from the text. The functionality of the TEI as a tool that bounds and labels data into discrete elements allows me to explore the indeterminate boundaries of these queer themes in the text. The strict nature of this tool compels literary researchers like myself to see how working with textual data in electronic formats will surface that which evades their grasp.

Textual Scholarship

To inform my approach for handling homoerotic subject matter within digital contexts, I bring two fields, Textual Scholarship and Queer Historiography, into conversation. The debates within these fields allow me to carve out a methodology for digitizing what electronic editing scholar Jerome McGann calls our ‘textual inheritance’ (McGann, 2001: xi). Here, I identify a parallel debate between what I term the ‘restorative’ and ‘productive’ approaches to Textual Scholarship and Queer Historiography. In the field of Textual Scholarship, the restorative approach promotes editorial practices that increasingly delimit the role of the editor as a recoverer or preserver of texts, while the productive approach empowers the editor as an enabler of potential textual readings. The history of Textual Scholarship first tends toward the restorative approach, beginning with the work of Shakepearean scholar Ronald B. McKerrow, who maintains that the goal of scholarly editing is to preserve authorial intention. McKerrow’s influential model for ‘copy-text’ editing, which establishes the base-text for editing on an early witness that most closely resembles the author’s original intention, eventually gives way to Walter W. Greg’s approach that expands the purview of critics to more than a single witness. Subsequently, Fredson Bowers and Thomas Tanselle advance Greg’s work, proposing the ‘eclectic edition’ as the format that enables the editor to distil authorial intention from multiple sources.1 Tanselle, in particular, enshrines the role of the editor as the only figure capable of realizing the ‘work’ in its ideal form:

Those who believe that they can analyze a literary work without questioning the constitution of a particular written or oral text of it are behaving as if the work were directly accessible on paper or in sound waves … [but] its medium is neither visual nor auditory. The medium of literature is the words (whether already existent or newly created) of a language; and arrangements of words according to the syntax of some language (along with such aids to their interpretation as pauses or punctuation) can exist in the mind, whether or not they are reported by voice or in writing. (Tanselle, 1989: 16–17)

Because the act of inscription involves physical tools that corrupt the writer’s pure ideas, the writer requires an editor whose distance from the creation of the work enables his objective evaluation of its intention. Tanselle’s prioritization of textual recovery exemplifies the restorative approach.

Toward the end of the 20th century, D. F. McKenzie’s ideas about ‘the sociology of texts’ challenge the claim that a single text can represent an ‘ideal’ version. According to McKenzie, the book is never one single object but stems from a number of human agencies and mechanical techniques that are historically situated: ‘Every society rewrites its past, every reader rewrites its texts, and if they have any continuing life at all, at some point every printer redesigns them’ (McKenzie, 1986: 25). Jerome McGann expands this sociological perspective into digital editing environments, where electronic formats create opportunities for presenting textual variation. McGann explains that textual criticism in print format is limited because a print text must conform to the linear and two-dimensional form of the codex: the same form as its object of study. Digital editions, by contrast, can be designed for complex, reflexive, and ongoing interactions between reader and text. McGann notes that his work on the digital Rossetti Archive brought him to repeatedly reconsider his earlier conception and goals, explaining that the archive ‘seemed more and more an instrument for imagining what we didn’t know’ (McGann, 2001: 82). McGann’s approach counters the traditional fidelity toward authorial intention with a drive to harness the potentiality of textual variation. The transformation of literary material into electronic format becomes a vehicle for a critical analytical method that McGann and Lisa Samuels call ‘deformative criticism’, which works by distorting, disordering, or re-assembling literary material in order to estrange the reader from their familiarity of the text. Continually subscribing the text to new configurations, this estrangement confronts the reader with new insights about its formal significance and meaning. For that reason, deformative criticism encourages a productive approach to editing.

Queer Historiography

Two competing approaches in the field of Queer Historiography parallel the ‘restorative’ and ‘productive’ approaches from Textual Scholarship. Susan McCabe defines ‘Queer Historicism’ as the ‘critical trend of locating “identifications” (rather than identity), modes of being and having, in historical contexts’ (McCabe, 2005: 120). In this field, critics often debate the extent to which they, in the present, can adequately describe queer identifications from the past. On the ‘restorative’ side, there is the Queer Historicist position advocated by scholars like David Halperin and Valerie Traub, who maintain that homosexuality is historically constructed; that ‘queerness’ means something different today than it did in the past, and that we can get at its meaning by employing a Foucauldian genealogical method that traces its meaning over time. Halperin, in particular, characterizes homosexual identity as a modern cultural production: ‘no single category of discourse or experience existed in the premodern and non-Western worlds that comprehended exactly the same range of same-sex sexual behaviors … that now fall within the capacious definitional boundaries of homosexuality’ (Halperin, 2000: 88). By contrast, the ‘unhistoricists’, including Jonathan Goldberg and Madhavi Menon, are wary of demarcating queer subjectivity across history in ways that imply progress (Goldberg, J and Menon, M, 2005). These scholars maintain that the attempt to define ‘queer’ would subscribe queerness to heteronormative teleology, which has the effect of normalizing (and therefore evacuating) queerness: ‘to produce queerness as an object of our scrutiny would mean the end of queering itself’ (1609, 1608). In response to this unhistoricist position, Valerie Traub maintains that ‘queer’ depends on historical specificity:

Queer’s free-floating, endlessly mobile, and infinitely subversive capacities may be strengths—allowing queer to accomplish strategic maneuvers that no other concept does—but its principled imprecision implies analytic limitations … if queer is intelligible only in relation to its social norms, and if the concept of normality itself is of relatively recent vintage (Locherie), then the relations between queer and the changing configurations of gender and sexuality need to be defined and redefined. (Traub, 2013: 33)

According to Traub, queerness requires historical specificity in order to be legible. If applied ahistorically, the term ‘queer’ would lose its descriptive value. The position that queer can be defined and redefined across historical periods aligns the historicists with the restorative impulse in Textual Scholarship, while the unhistoricist refusal to circumscribe such a definition recalls the productive approach.

Heather Love refocuses this methodological debate to emphasize the relationship between the critic and the object of study. Love makes the argument that, although the queer historian cannot validate the queerness of the past, the project of queer history must continue. Love explains that ‘Queer history has been an education in absence: the experience of social refusal and of the denigration of homosexual love has taught us the lessons of solitude and heartbreak’ (Love, 2009: 52). Her methodology takes negative affects like shame, anger, disgust, hatred, disappointment as phenomena that cannot be resolved, recuperated, or rescued by the queer historian because queer subjects will always fail to fit within contemporary conceptions of identity and desire. Rather than attempt to ‘fix’ the past, however, Love offers the methodology of ‘feeling backward’, an accounting of ‘the social, psychic, and corporeal effects of homophobia’ (2). By ‘feeling backward’, Love is interested in exploring the way that subjects turn away or refuse the critic’s attempt to ‘redeem’ or ‘rescue’ them: she offers the myth of Orpheus and Eurydice, pointing out that Orpheus prefers to behold Eurydice in the darkness of the Underworld rather than in the sunlight.2 Bringing Eurydice into the light of day would transform her into something fully accessible and therefore less desirable. This is a crucial lesson for queer critics: ‘[Eurydice’s] specific attraction for queer subjects is an effect, I want to argue, of a historical experience of love as bound up with loss. To recognize Eurydice as desirable in her turn away is a way of identifying through that loss’ (Love, 2009: 51).

Plagued by the problem of what to do with the past, the critic attempts to ‘rescue’ queer figures in a way that evokes Tanselle’s aim to recover the ideal text in scholarly editing. Love, however, asserts that this rescue is impossible:

Such is the relation of the queer historian to the past: we cannot help wanting to save the figures from the past, but this mission is doomed to fail. In part, this is because the dead are gone for good; in part, because the queer past is even more remote, more deeply marked by power’s claw… Such a rescue effort can only take place under the shadow of loss and in the name of loss; success would constitute failure. (Love, 2009: 51)

Perhaps this impossibility allows the critic to rethink how she might preserve the queer textual inheritance: accepting queerness as something that eludes containment compels her to explore how queerness escapes certain kinds of analyses. Love suggests ‘a mode of historiography that recognizes the inevitability of a “play of recognitions” but that also sees these recognitions not as consoling but as shattering’ (Love, 2009: 45). By ‘play of recognitions’, Love means the inevitable ‘search for roots and resemblances’ enacted by the critic when she encounters queer subject matter (45). I propose that this method of attending to queerness as elusive, without trying to transform it into something more palatable, can apply to digital contexts and toward productive ends. One may, borrowing from McGann and Samuel’s idea of deformance, reconceive textual editing as a formal experiment. The TEI can be used to explore how electronic editing tools impose new formal structures on queer subject matter. This allows one to take the attempt at recovery and, rather than aim for resolution, multiply the potential readings of textual elements. Using the TEI in this way allows researchers to direct ‘queer encoding’ practices toward enacting what Kadji Amin, Amber Jamilla Musser, and Roy Pérez describe as ‘queer form’, or ‘the range of formal, aesthetic, and sensuous strategies that make difference a little less knowable, visible, and digestible’ (2017: 235).

My work encoding Wilde’s revisions to the manuscript plays against the long-standing ‘recovery’ project about Wilde’s intentions as he revises Dorian Gray into the periodical and book versions. Textual scholars like Donald Lawler, Joseph Bristow and Nicolas Ruddick claim that Wilde’s revisions work toward the overall goal of aestheticizing the text. This project of aestheticization begins in the manuscript which is eventually published, in periodical form, in Lippincott’s Monthly Magazine on June 20, 1890.3 This first printing of ‘The Picture of Dorian Gray’, which spans 98 pages over 13 chapters, was widely criticized in the press for its seemingly ambiguous stance on an immoral protagonist. Bristow explains that ‘[Wilde’s] narrative struck the [reviewers] as a work that appeared “corrupt”, displayed “effeminate frivolity”, and dealt “with matters only fitted for the Criminal Investigation Department”’ (2000: xviii). Wilde spends the next several days defending his work in letters to the editors, entering into a public correspondence with them.4 A few months later, in the early spring of 1891, Wilde publishes a ‘Preface’ that makes such claims as ‘Those who find ugly meanings in beautiful things are corrupt without being charming. This is a fault’ and ‘To reveal art and conceal the artist is art’s aim’.5 Scholar Barbara Leckie asserts that, by these complex and incisive statements, ‘Wilde’s strategy is to refocus on art and disparage the focus on the reader by saying that the reader is the one who makes a work immoral’ (2013: 173). Similarly, Lawler argues that ‘the “Preface” … hold[s] up aesthetic beauty and artistic effect as the only legitimate criteria of critical evaluation’ (1988: 16). The ‘Preface’ is included in the subsequent iteration of Dorian Gray, published in a book version by Ward, Lock & Company in April 1891. According to the editor of the Uncensored Edition of Dorian Gray, Victor Frankel, Wilde here makes significant deletions of passages referencing homosexuality, promiscuous or illicit heterosexuality, and ‘anything that smacked generally of decadence’ (2011: 47–48). Wilde also ‘heighten[s] Dorian’s monstrosity toward the novel’s conclusion’ to bring the story ‘to a moral conclusion that he thought would silence his critics’ (Frankel, 2011:30).

TEI

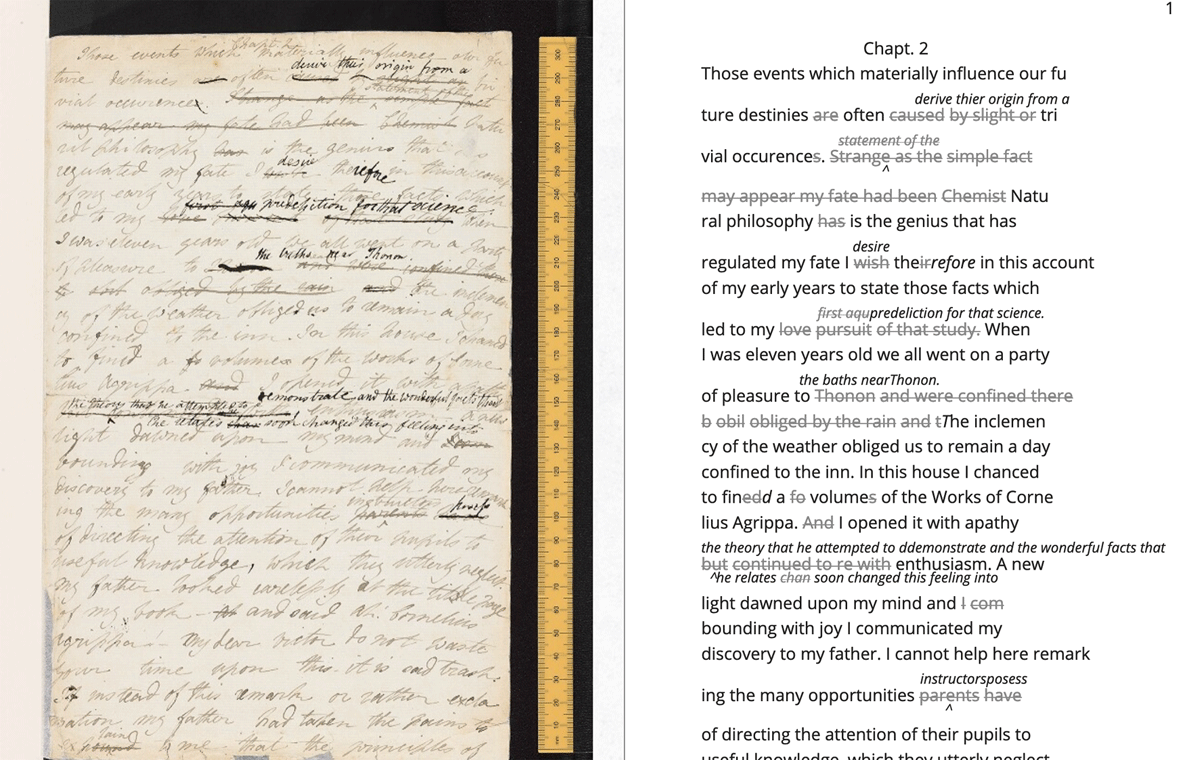

Created specifically for working with literary material, the TEI enables researchers to describe, transcribe and edit print text or manuscripts in electronic format. The TEI enables users to ‘mark up’ aspects of literary texts that they think are important, such as structural elements (chapters, paragraphs, line breaks), physical details about the text (revisions, illegible text) or conceptual elements (persons, geographical locations). To mark up these elements, encoders use ‘tags’, such as <line> to indicate a line of text, <del> to indicate deleted text, and <person> for a reference to a person. Below is an image of Mary Shelley’s manuscript of Frankenstein; or, The Modern Prometheus (1818) and its diplomatic transcription (see Figure 1). Beneath this image is an excerpt of the underlying TEI code, both created by the Shelley-Godwin Archive.

Image of the manuscript and diplomatic transcription of Frankenstein (Bodleian MS Abinger c.56: 1816), transcribed and encoded by the Shelley-Godwin Archive (The Shelley-Godwin Archive. University of Maryland, College Park).

In the encoding, the <line> tags indicate lines of text, and <del> tags indicate deleted text. Through this level of detail, TEI facilitates deep and complex description of textual material. This excerpt also includes a <handShift> tag and @hand attribute, which indicate whose ‘hand’ is responsible for writing each section of text: a valuable piece of information for a text co-edited by Shelley’s husband, Percy Shelley.

TEI documents resemble an ordered hierarchy containing a nested tree structure, with one ‘root’ component and several ‘branches’, known as ‘nodes’. The TEI requires all elements in the text to be contained as discrete nodes within this bounded structure, and elements cannot overlap unless the inner element is fully nested within an outer element. Though the strict tagging structure of the TEI forces encoders to organize textual elements as discrete, ordered data, it also enables them to create their own labels for the elements. Perhaps the most useful aspect about the TEI is this customizability, which it inherits from its parent language, eXtensible Markup Language (XML). As an ‘extensible’ language, TEI users can create their own tags to describe the particular elements they wish to encode. The Women Writers Project (WWP), directed by Julia Flanders, adequately frames how TEI’s inherent extensibility can address textual ambiguity. According to the WWP:

Unlike many standardization efforts, the TEI … explicitly accommodat[es] variation and debate within its technical framework. The TEI Guidelines are designed to be both modular and customizable, so that specific projects can choose the relevant portions of the TEI and ignore the rest, and can also if necessary create extensions of the TEI language to describe facets of the text which the TEI does not yet address. (Flanders, 1999–2021)

Because TEI is built from a language that allows its users to build their own version of that language, there is potential for representing the elements necessary for a project by customizing these elements on a project-by-project basis.

As queer studies scholars may know, however, some textual elements will resist containment within any kind of category. Accordingly, there are a number of projects that explore the potential of the TEI for ‘queer encoding’, such as the encoding of queer gender. The <person> tag, which describes persons referenced within a text, is limited to one value for gender, which creates obstacles for scholars working to encode multiple or diverse sexual identities. Pamela Caughie and Sabine Meyer, for example, use the the TEI to encode Man Into Woman, the life narrative of Danish painter Lili Elbe, who undertook one of the first gender affirming surgeries in 1930. The attempt to mark up Elbe’s complex gender ontology brings Caughie and Meyer against this structural limitation of the TEI:

[T]he deeper we got into mark-up, the more evident it became that the categories and hierarchies available to us were inadequate for our task… to identify a male subject who at times presents himself as masquerading as a woman, at others as being inhabited by one, and who eventually becomes a woman, in a life history narrated retrospectively from the perspective of Lili Elbe. (Caughie, P L, Datskou, E and Parker, R, 2018: 231)

The TEI forces these scholars to consider the ways that computation works on a deeper level to reify gender as essential. In particular, the fixity that the TEI imposes upon Elbe as a queer subject brings out the ways that gender is situated and relational across this text.

Other scholars find advantage in the TEI’s strict data structure. While the TEI limits what constitutes a person—as an entity with one sex, for example—it also enables an approach toward personhood as multiple. Like Caughie and Meyer, Marion Thain also works to encode the diaries of a complex writing subject: the late 19th-century English poet, Michael Field. Michael Field is a pen name for the lesbian couple, Katharine Bradley and Edith Cooper, which signifies ‘the assumed names of two separate women, as well as appearing to signify one single male identity’ (Thain, 2016: 228). Fortunately for Thain, the TEI enables the encoding of distinct identities, which is central for understanding the queerness of the diaries:

[T]he proliferation and slipperiness of names is no mere childish caprice but a core part of the articulation of queer: an unhinging of ‘given’ or apparently predetermined identity through a strategy that articulates identity as constantly shifting, constructed, and performative. Text encoding can, in a simple but powerful way, help us explore and map this crucial strand of queer identity construction across the diary. (Thain, 2016: 233)

Thain’s approach harnesses the hierarchical nature of the TEI to list the various references to each personage within the <persName> tag. This <persName> tag allows Thain to ‘render searchable words not in the text but intimately tied to it. This is not a small issue in a diary in which Katharine Bradley herself is referred to by more than 20 different names’ (Thain, 2016: 233). The TEI data structure enables Thain to manage the problem of queer identity by encoding multiple personages that refer to either Katharine Bradley or Edith Cooper.

Why do Caughie and Meyer struggle to encode Elbe’s identity while Thain appears to succeed with Fields’? While a queerness like Fields’ might be delineated and contained, in Elbe’s there is a quality of blending which the markup, by its nature, means to separate and fix. As Flanders points out, markup is a tool for naming, bounding, and containment, and therefore registers information in distinct components (Flanders, 2017). Fields’ identity is multiple yet distinct: the diaries proffer ‘two different hands [that] record the experience of two clearly differentiated people’ (Thain, 2016: 229). By contrast, Elbe’s identity is plural, containing several identities whose relationship to each other is ambiguous or continually shifting within one entity. Elbe’s relation to gender is best described qualitatively, as one that alternatively ‘masquerades’ or ‘inhabits’ simultaneous gender ontologies (Caughie, P L, Datskou, E and Parker, R, 2018: 231).

The Manuscript of Dorian Gray

For Wilde’s text in particular, I created a customization that explores the potential of semantic labelling against the demands for fixity and structure within the TEI schema. My customization registers physical and conceptual changes to the manuscript by creating two new attributes to mark the revisions. First, to mark the physical traces of Wilde’s pen as he struck out portions of the text, the custom attribute, ‘strokes’ (@strokes in formal TEI notation), registers the number of pen strokes through any given section of text.6 Most often, Wilde uses one or two strokes of his pen, although sometimes, the strokes are too heavy or thick to enumerate. In those cases, I set the @strokes attribute to the value ‘inconclusive’. In addition to @strokes, the custom attribute @implication marks the general theme of revision from a list of recurring themes, which include: ‘intimacy’, ‘beauty’, ‘passion’, and ‘fatality’, with the additional values of ‘inconclusive’ or ‘illegible’.

In what follows, I detail how this customization registers the elisions of homoeroticism in the manuscript as Wilde prepared it for publication. The goal of this work is not to establish a formal method for marking queer elements, rather, it is to ‘search for potential’ resistance in the text: to explore how it works with or against containment by the TEI data structure. Here, the difficulty is in engaging the boundedness of the TEI elements, which encapsulate data, with the indistinctiveness of the queerness of the text, which resists demarcation. The four themes of ‘intimacy’, ‘beauty’, ‘passion’, and ‘fatality’ constitute a spectrum of smooth information that checks the confines of the TEI tags. To add another layer of ambiguity, the number of pen strokes also resists easy demarcation: they can be difficult to enumerate and their boundaries often fail to map with the themes. Therefore, in order to mark up this text, I impose editorial decisions on the data.

The evocative opening scene, which consists of a lively dialogue between Basil Hallward and Lord Henry Wotton, sets the tone, reveals character dynamics, and lays out some of the conflict for the ensuing story. In these first few pages, Basil appears to be a sympathetic, sensitive, albeit slightly exasperated artist, who confides in his close friend Lord Henry the powerful influence that Dorian Gray has had upon his life and work. Lord Henry, by contrast, appears as an affable and witty gentleman aesthete, who counters Basil’s sincerity with offbeat observations and paradoxical aphorisms. From the revisions made to this opening scene, a few general patterns emerge. First, the revisions work to stifle the emotional tension and physical affection in the dialogue between Basil and Lord Henry, replacing it with a lighter or more neutral tone. Because these revisions generally shore up the friendship between Basil and Lord Henry, conveying fondness in their rapport, they are encoded according to the theme of ‘intimacy’. Second are the themes of ‘beauty’ and ‘passion’, which mostly concern revisions where Dorian is reformulated from a romantic object into an artistic subject for Basil’s painting. Third, and finally, is the theme of ‘fatality’, which emerges in moments where Basil struggles to explain the consuming and self-destructive effects of Dorian’s influence on his life.

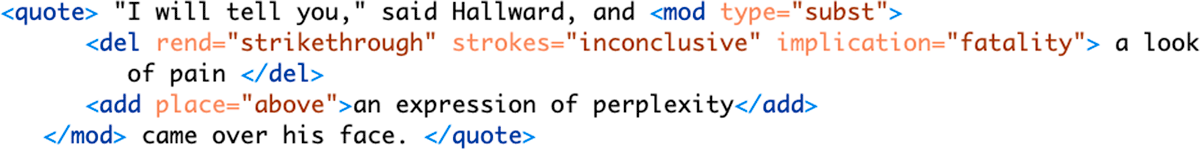

On the theme of intimacy, Wilde’s pen slashes through evidence of physical contact between Basil, Lord Henry, and Dorian. This includes the following: ‘taking hold of his [Lord Henry’s] hand’ (9), Dorian’s ‘cheek just brushed my [Basil’s] cheek’ (20), Basil and Dorian ‘sit beside each other’ (22). Additionally, the dialogue between Basil and Lord Henry develops intimacy through their tone and subtle mannerisms, which facilitates Basil’s confession of his feelings for Dorian. In some of his revisions, Wilde diminishes this intimacy in their conversation with the effect of mitigating the sense of foreboding that surrounds Basil’s attraction to Dorian. Here, Wilde replaces tense pauses with laughter or exchanges dramatic statements and descriptions with more playful ones. One such example occurs when Basil struggles to convey his reasoning for refusing to exhibit Dorian’s portrait:

‘The reason why I will not exhibit this picture, is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.’

Lord Henry hesitated for a moment. ‘And what is that?’ he asked, in a low voice. ‘I will tell you,’ said Hallward, and a look of pain came over his face. ‘Don’t if you would rather not,’ murmured his companion, looking at him. (9)

The revised version in the manuscript, incorporating the deletions and interlinear additions, reads:

‘The reason why I will not exhibit this picture, is that I am afraid that I have shown in it the secret of my own soul.’

Lord Henry laughed. ‘And what is that?’ he asked. ‘I will tell you,’ said Hallward, and an expression of perplexity came over his face. ‘I am all expectation Basil,’ murmured his companion, looking at him. (9)

Here, several changes mitigate the emotions of the scene. First, rather than ‘hesitate’, Lord Henry ‘laugh[s]’, and he no longer speaks ‘in a low voice’. The effect is to overwrite a previously intimate moment with levity. Basil also exchanges his facial expression from one of agony to confusion when ‘a look of pain’ transforms into ‘an expression of perplexity’. Lastly, Lord Henry, rather than sympathizing with Basil, instead encourages him to speak: ‘I am all expectation, Basil’. Together, these changes work to obscure Basil’s internal suffering with the effect of lightening the mood of the scene.

Another example similarly tempers the intense, emotional energy while also mitigating a sense of anxiety or foreboding. It occurs on the following page, where Basil is on the verge of revealing the reasons behind his attraction to Dorian. The original dialogue proceeds: ‘Lord Henry felt as if he could hear Basil Hallward’s heart beating, and he heard his own breath, with a sense almost of fear. “Yes. There is very little to tell you,” whispered Hallward, “and I am afraid you will be disappointed. Two months ago…”’ (10). The manuscript’s revised version reads: ‘Lord Henry felt as if he could hear Basil Hallward’s heart beating, and he wondered what was coming. “Yes. There is very little to tell you,” whispered Hallward rather bitterly, ‘and I dare say you will be disappointed. Two months ago…”’ (10). Here, rather than draw attention to Lord Henry’s breathing, Wilde mentions Lord Henry’s ‘wonder’ about Basil’s pending explanation, which shifts Lord Henry’s sense of anticipation from fear to curiosity. Wilde also makes slight changes to Basil’s delivery: in the revised version, Basil speaks ‘rather bitterly’ and uses the expression ‘I dare say’ rather than ‘I am afraid’. Both changes diminish the confessional tone that originally precedes Basil’s revelation about Dorian Gray. In this change, and in the aforementioned passage, the close rapport, the ‘intimacy’, between Basil and Lord Henry enables Basil’s confession about the self-consuming qualities of his feelings for Dorian, thus evoking the theme of ‘fatality’. The data structure of the TEI, however, fails to capture this complicated dynamic because the @implication attribute is limited to one value. Therefore, the encoder must choose one theme per item of revision, either ‘intimacy’ or ‘fatality’.

Throughout this chapter, Wilde often swaps out words with the effect of diluting or diverting their original connotation. He focuses this type of revision on Basil’s dialogue, when Basil speaks about his passionate attachment to Dorian and the effect of Dorian’s beauty upon his art. Here, Wilde trades expressive nouns with words that convey relatively weaker or more generalized ideas. For example, in the sentence ‘Every portrait that is painted with passion is a portrait of the artist, not of the sitter’, Wilde replaces ‘passion’ with ‘feeling’ in the manuscript (9), exchanging the romantic connotation of ‘passion’ with the more neutral one of ‘feeling’. Additionally, on the theme of ‘passion’, Wilde substitutes words and phrases which connote a strong sense of romantic passion for ones that emphasize an aesthetic interest. One line, prior to revision, reads: ‘I knew that I had … come across someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that it would be Lord over my life, my soul, my art itself’ (11). Wilde revises this line to: ‘I knew that I had come face to face with someone whose mere personality was so fascinating that it would absorb my nature, my soul, my art itself’ (11). Here, Wilde swaps out ‘life’ for ‘nature’, with the effect of subscribing Dorian’s influence to his ‘nature’, that is, part of his personality or behavior, rather than encompassing his ‘life’. Wilde also replaces ‘be Lord over’ with ‘absorb’, which maintains Basil’s sense of submission to an external force without the patriarchal designation in ‘Lord’. These changes, which are encoded under the theme of ‘passion’, diffuse a consuming quality in Basil’s attraction into a sensitivity to Dorian’s aesthetic influence. Like the revisions to the theme of ‘intimacy’, the subtle changes of word choice in this section also begin to gesture to the theme of fatality, which fully develops over the next several pages.

In addition to words associated with ‘passion’, Wilde often replaces the word ‘beauty’ in Basil’s references to Dorian. In doing so, Wilde neutralizes the power of Dorian’s physical allure. For example, Wilde changes ‘Suddenly I found myself face to face with the young man whose beauty had so stirred me’ to ‘Suddenly I found myself face to face with the young man whose personality had so strangely stirred me’ (13, my emphasis). The shift from ‘beauty’ to ‘personality’ allows Basil to avoid mentioning Dorian’s physical appearance, and the addition of ‘strangely’ serves to mystify Dorian’s influence over Basil. Throughout the rest of chapter, Wilde makes several changes that similarly dilute Dorian’s powerful appearance: he replaces ‘beauty’ with ‘good looks’ and then with ‘face’ two separate times (6, 18). Finally, in reference to Dorian Gray, the word ‘Narcissus’ is replaced with ‘man’ (13). Like the previous changes on the theme of ‘passion’, the changes in words associated with ‘beauty’ shift the original connotation. Here, the decision to replace ‘beauty’ with references to ‘face’ or ‘good looks’ maintains the emphasis on the physical while muting the suggestive power of ‘beauty’ in the abstract. In doing so, connotations about the ideal, the charming, and the alluring, which usually accompany descriptions of beauty, are diffused into physical description. This evacuates Dorian’s mysterious allure and diminishes the overwhelming influence that he holds over Basil.

Removing associations with beauty and passion is part of Wilde’s larger effort of aestheticizing Dorian, transforming him from an erotic object into an aesthetic object. At the end of the first chapter, Basil implores Lord Henry to refrain from influencing the impressionable youth. The original version reads:

‘Don’t take away from me the one person that makes life lovely for me. Mind, Harry, I trust you.’ He spoke very slowly, and the words seemed wrung out of him, almost against his will.

‘I don’t suppose I shall care for him, and I am quite sure he won’t care for me,’ replied Lord Henry smiling, and he took Hallward by the arm, and almost led him into the house. (27–28)

Lord Henry’s assurance that neither he nor Dorian shall ‘care for’ each other characterizes Basil’s passionate feelings for Dorian as a kind of general possessiveness. However, the source of Basil’s anxiety is specified with the next revision:

‘Don’t take away from me the one person that makes life absolutely lovely to me, and that gives my art whatever wonder or charm it possesses. Mind. Harry, I trust you.’ He spoke very slowly, and the words seemed wrung out of him almost against his will.

‘What nonsense you talk,’ said Lord Henry smiling, and, taking Hallward by the arm, he almost led him to the house. (27, 27B)

In this revision, Basil attributes an aesthetic value to Dorian, asserting Dorian’s importance for his art, giving it ‘whatever wonder or charm it possesses’. Lord Henry’s response moves from reassurance to dismissal, rejecting Basil’s anxiety as ‘nonsense’ and ending the scene on a slightly humorous note. Across these changes, Wilde refocuses Basil’s jealous passion into an anxiety about losing Dorian as an artistic subject. Additionally, the shift from sincere reassurance to light-hearted repartee in Lord Henry’s response evacuates the strong emotional tone of the scene, replacing it with friendly banter. The effect is to divert Basil’s passion for Dorian toward aesthetic appreciation.

Wilde’s efforts in redirecting Basil’s passion toward artistic ends is inextricable from the attempts to soften Basil’s intense and consuming devotion to Dorian, which emerges in references to Basil’s troubled state of mind. One example occurs when Basil recounts his first time meeting Dorian: ‘I had a strange feeling that Fate had in store for me exquisite joys and exquisite sorrows. I knew that if I spoke to him, I would never leave him till either he or I were dead. I grew afraid, and turned to quit the room’ (12). Here, Basil’s passion swells with an intense, life-threatening quality that Wilde’s pen works to mitigate by removing the association with death. He crosses through ‘never leave him till either he or I were dead’ and adds ‘become absolutely devoted to him, and that I ought not to speak to him’. Wilde again tempers this self-consuming quality of Basil’s devotion when he changes the phrase ‘I could not live if I did not see him every day’ to ‘I couldn’t be happy if I didn’t see him every day’ (17). By shifting the focus from Basil’s ‘life’ to his happiness, Wilde dilutes the profound peril that Basil’s passion has generated.

The TEI data structure reinforces the difficulty of disambiguating the themes of passion and fatality. In the phrase discussed above, ‘look of pain’ is revised to ‘an expression of perplexity’ (9).7 Working with this revision in the TEI presents two points of contention (see Figure 2). First, in categorizing the theme, does the phrase ‘look of pain’ express passion or fatality? On the one hand, ‘pain’ denotes a strong, passionate feeling; on the other, Basil often draws on pain in his references to the fatalistic qualities about his attraction to Dorian, as in the following quote which was deleted: ‘I feel, Harry, that I have given away my whole soul to someone seems to take a real delight in giving me pain’ (23). The difficulty of disambiguating the theme is mirrored by the strokes of Wilde’s pen, which vary even across the same phrase: while the word ‘look’ is struck so heavily that the number of strokes is inconclusive, the word ‘pain’ contains a single stroke. With the TEI, it is impossible to mark the variations in strokes without separating the single revision into two instances, which would break up the integrity of the phrase. Therefore, it is marked with the value ‘inconclusive’. The difficulty with marking up the pen strokes deepens when considering the semantics of the revision: the heavier strokes are focused on a revision (‘look’ to ‘expression’) that carries less semantic weight than the single stroke (‘pain’ to ‘perplexity’). The reasoning behind the relationship between the themes and the strokes thus remains recalcitrant.

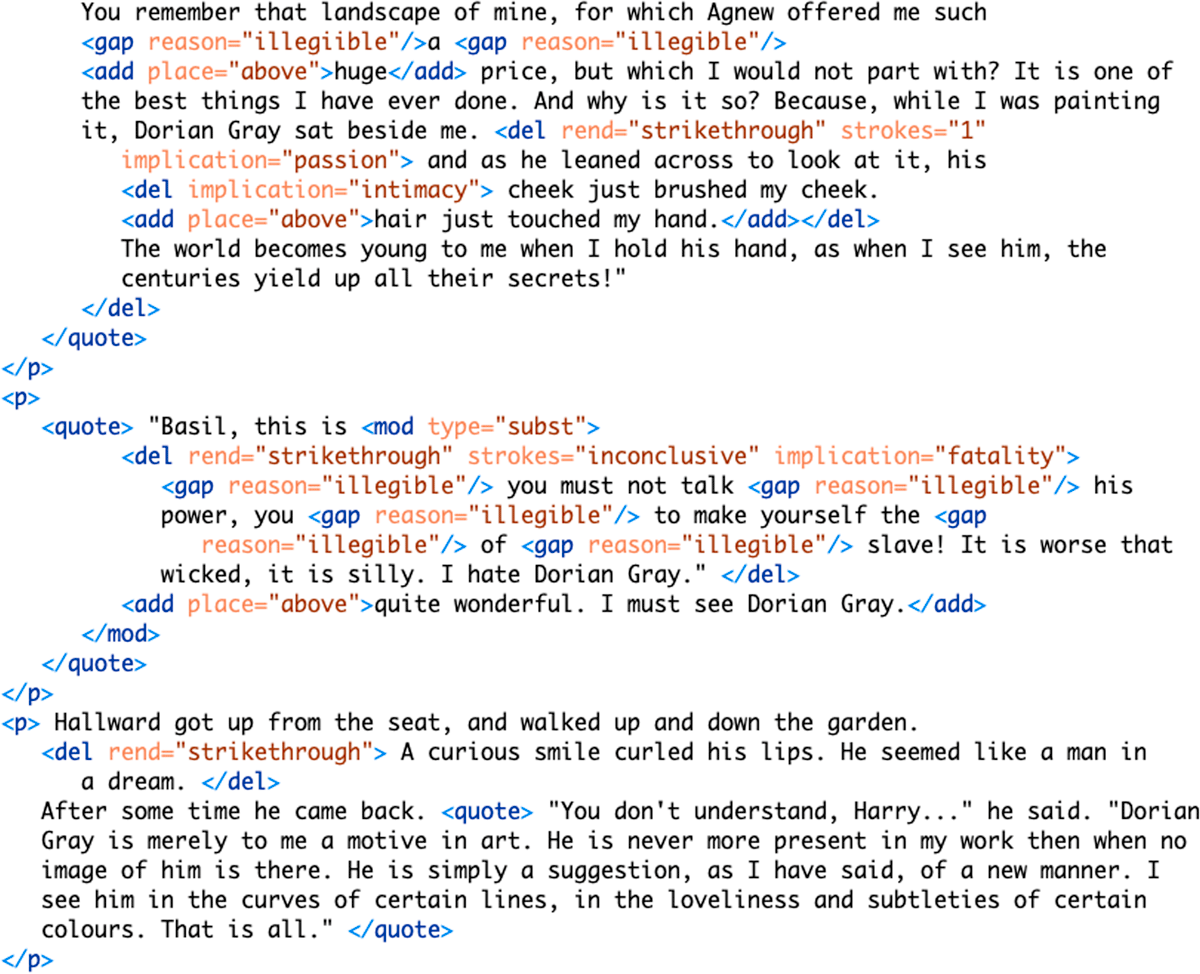

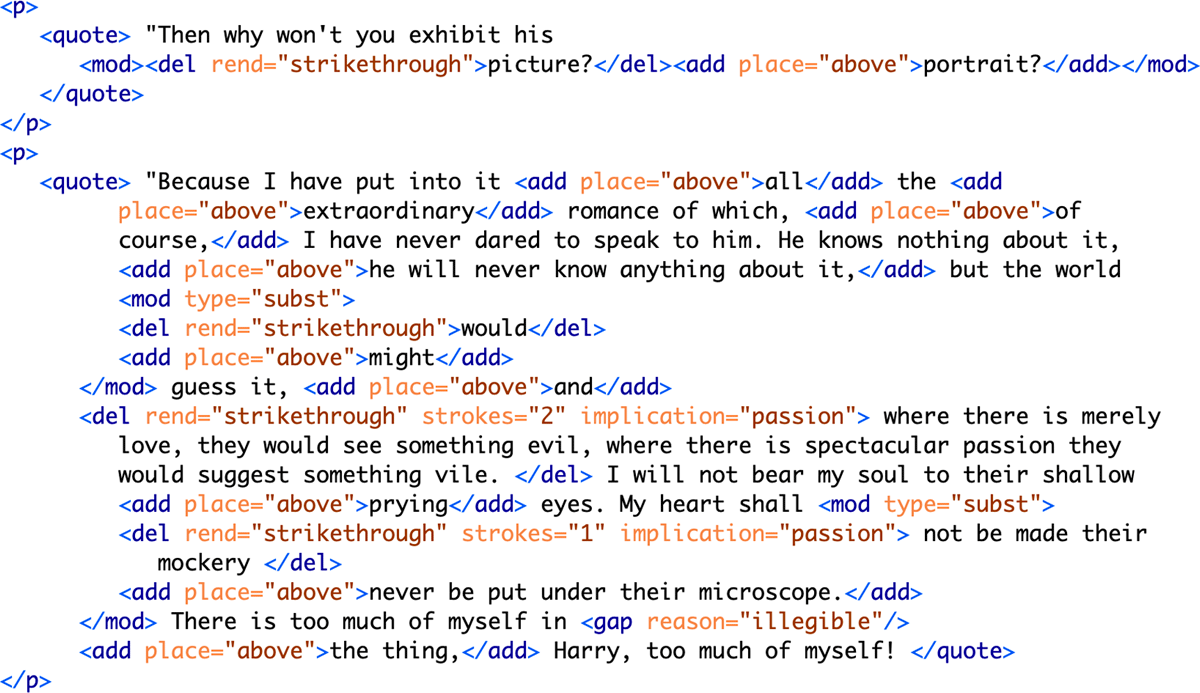

My final example concerns a longer passage that was heavily revised in the manuscript.8 The treatment of this passage crystallizes the various patterns of revision seen so far—diminishing signs of intimacy, passion, and references to Basil’s fatalism. The passage in the manuscript bears quoting in full. Prior to any revisions, it reads:

‘You remember that landscape of mine… It is one of the best things I have ever done. And why is it so? Because, while I was painting it, Dorian Gray sat beside me, and as he leaned across to look at it, his cheek just brushed my cheek. The world becomes young to me when I hold his hand, as when I see him, the centuries yield up all their secrets!’

‘Basil, this is [illegible] you must not talk [illegible] [illegible] his power, [indecipherable] to make yourself the [illegible] slave! It is worse than wicked, it is silly. I hate Dorian Gray.’

Hallward got up from the seat, and walked up and down the garden. A curious smile curled his lips. He seemed like a man in a dream. After some time he came back. ‘You don’t understand, Harry…’ he said. ‘Dorian Gray is merely to me a motive in art. He is never more present in my work then when no image of him is there. He is simply a suggestion, as I have said, of a new manner. I see him in the curves of certain lines, in the loveliness and subtleties of certain colours. That is all.’

‘Then why won’t you exhibit his picture?’

‘Because I have put into it the romance of which I have never dared to speak to him. He knows nothing about it, but the world might guess it, where there is merely love, they would see something evil, where there is spectacular passion, they would suggest something vile.’ (20–21)

The TEI surfaces Wilde’s layers of revision in this passage (see Figures 3 and 4). In the first paragraph, Wilde eliminates a span of text from ‘and as he leaned’ to ‘secrets!’. Within this span, Wilde makes additional changes, adding text such as ‘hair just touched my hand’. Due to its physical nature, this particular phrase is marked as ‘intimacy’ in the TEI, while the longer section is enclosed by the label of ‘passion’, which denotes the nature of the other revisions within the same sentence, like ‘The world becomes young to me when I hold his hand’. Here, the TEI enables a layered approach to markup where one element can be nested within another.

While the first paragraph is legible, the next one, by contrast, is almost completely blotted out. It consists of Lord Henry’s condemnatory and jealous protestations: ‘his power’, ‘to make yourself the … slave!’ and ‘I hate Dorian Gray’. Here, Wilde obscures the fatalistic connotations of Basil’s passion, which exasperate Lord Henry. Accordingly, the @implication is marked as ‘fatality’ and the @strokes are marked as ‘inconclusive’.

Most of the third paragraph is preserved, presumably for how it furthers Dorian’s aestheticization. Here, Basil elaborates upon Dorian’s aesthetic influence, which inspires his apprehension of the natural world. In the following paragraph, however, Wilde again obscures much of language, which revolves around the themes of passion and fatality. On the theme of fatality, the small adjustment of ‘would’ to ‘might’ eliminates a sense of inevitability about Basil’s feelings for Dorian. On the theme of passion, the revelatory line: ‘where there is merely love, they would see something evil, where there is spectacular passion, they would suggest something vile’ is completely struck out. This statement clarifies Dorian’s importance for Basil as the source of a powerful allure that suffuses Basil’s art with beauty. Notably, the strokes over the phrase ‘suggest something vile’ are doubled, which cannot be encoded in the TEI without separating the revision into two instances. As with the deletion of ‘look of pain’ (9), marking each element here with precision would require separating into distinct entities what is in fact one act of revision that contains plural implications. It would involve resolving Wilde’s perhaps indeterminate motives into a single intention.

On one level, the TEI encoding reinforces the claim by Lawlor, Frankel, and Bristow that Wilde diminishes the homoerotic elements by transforming Dorian from an erotic into an aesthetic object. This goal is achieved in three ways: first, by easing the tension surrounding his dialogue with Lord Henry; second, by emphasizing Dorian as an ideal subject for art; and finally, by removing the destructive connotations of Basil’s attachment to Dorian. On a deeper level, however, the existing textual scholarship has yet to contend with the complex ways in which the revisions muddle Wilde’s intentionality. To resolve some of the difficulty with encoding this text, one might employ more precise qualitative markers such as ‘tension’ in addition to ‘intimacy’, or ‘ardor’ and ‘devotion’, in addition to ‘passion’, for example. But creating more tags would dilute the analytical utility of the TEI encoding, which is meant to be precise, and not meant to be exhaustive. In this project, the TEI reveals that the themes of intimacy, beauty, passion, and fatality operate in blurred or inscrutable ways: at times they are plural, co-existing within a single line of text; more often, they are inextricable, with one enabling the other, like intimacy and passion which enable fatality; at other times, they enfold one within the other, encompassing a plurality of intentions. The TEI, which requires strict disambiguation, surfaces how these themes work together in ways that cannot be captured by its data structure.

Conclusion: Toward a Queer Form

As Heather Love points out, queerness will be ‘always bound up with loss’ and the attempt to ‘rescue’ or ‘recover’ it will only lead to inevitable failure (2009: 51). The TEI enables an approach toward editing in this text that complicates, rather than resolves, queerness. By encouraging encoders to impose a level of fixity on the text, the TEI allows them to discover exactly where queerness eludes containment. This computational constraint of the TEI is an enabling one: by surfacing moments of failed disambiguation, the TEI reinforces the encoder as the one who ascribes semantic value to Wilde’s revisions. This failed disambiguation is also productive: the practice of pinning something down only to realize that such intelligibility is impossible. The TEI has been productive precisely because it requires the encoder to construct labels for textual elements which cannot be fully recovered.

Accordingly, this practice in ‘queer encoding’ does not attempt to resolve the question of Wilde’s revisions but tags the homoerotic elements in such a way that allows them to retain some of their elusiveness. One may examine the formalizations produced by this TEI schema not for what it reveals about Wilde’s intentions, but for how it releases potential readings of the history of his composition, in other words, to mark and visualize its queer form: the elusive affects, repressed desires, and other coded elements of queerness within this text. The TEI confronts one with precisely that which escapes existing structures for knowing queerness, in order to suggest, without fully grasping, its ever-shifting permutations.

Notes

- See Bowers, F (1959); Greg, W W (1950–1951); McKerrow, R B (1950); and Tanselle, T (1989). [^]

- As the condition of rescuing his lover Eurydice from Hades, Orpheus must not look at her until they exit the Underworld and re-emerge into the sunlight. Unable to restrain himself, Orpheus turns to gaze at Eurydice as they are about to pass through the threshold. In this glimpse he manages to catch of his lover, she is already shrinking away into the darkness where she will be forever imprisoned. [^]

- See Wilde, O and Frankel, N (2011), pp. 40–54, for a more complete accounting of the role of John Marshall Stoddart (Wilde’s publisher) in preparing the typescript for publication. [^]

- See Wilde, O and Gillespie, M P (2007), pp. 358–374, for a selected list of full-length reviews from The Scots Observer, The St James Gazette and the Daily Chronicle, and Wilde’s responses. [^]

- See Wilde, O and Gillespie, M P (2007), pp. 3–4. [^]

- I am grateful to Jason A. Boyd for making this suggestion. [^]

- See Wilde, p. 9. Manuscript image available here: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/oscar-wilde/the-picture-of-dorian-gray/11. [^]

- See Wilde, p. 20. Manuscript image avaible here: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/oscar-wilde/the-picture-of-dorian-gray/22; and page 21: https://www.themorgan.org/collection/oscar-wilde/the-picture-of-dorian-gray/23. [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Amin, K, Musser, A J and Pérez, R 2017 ‘Queer Form: Aesthetics, Race, and the Violences of the Social,’ ASAP/Journal., (Vol. 2.2, May), 227–239. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/asa.2017.0031

Barnett, F, Blas Z, cárdenas, m, Gaboury, J, Johnson, J M and Rhee, M 2016 ‘QueerOS: A User’s Manual,’ (eds. Matthew K. Gold and Lauren Klein). Debates in the Digital Humanities, University of Minnesota Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5749/j.ctt1cn6thb.8

Blas, Z and cárdenas, m 2007–2012. transCoder: A Software Development Kit.

Bowers, F 1959 Textual & Literary Criticism. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511552885

Boyd, J A 2014 ‘The Texting Wilde Project: Thoughts on Tools for a Computer-Assisted Exegisis of a Biographical Corpus,’ The Text Encoding Initiative Conference and Members Meeting 2014. Evanston: October 22–24.

Caughie, P L, Datskou, E and Parker, R 2018 ‘Storm Clouds on the Horizon: Feminist Ontologies and the Problem of Gender.’ Feminist Modernist Studies 1.3, 230–242. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/24692921.2018.1505819

Flanders, J 2017 ‘Encoding Identity.’ Queer Encoding: Encoding Diverse Identities. The Digital Scholarship Center, Temple University, April 28.

Flanders, J 1999–2021 ‘What is the TEI?’ The Women Writers Project.

Gaboury, J 2013 ‘A Queer History of Computing.’ Rhizome.org.

Gaboury, J 2018 ‘Becoming NULL: Queer relations in the excluded middle.’ Women & Performance: a Journal of Feminist Theory 28.2, 143–158. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/0740770X.2018.1473986

Goldberg, J and Menon, M 2005 ‘Queering History.’ PMLA, 120.5, 1608–1617. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1632/003081205X73443

Greg, W W 1950–51 ‘The Rationale of Copy-Text.’ Studies in Bibliography, 3, 19–36.

Halperin, D M 2000 ‘How to Do the History of Male Homosexuality.’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 6.1, 87–123. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-6-1-87

Lawler, D L 1988 An Inquiry into Oscar Wilde’s Revisions of the Picture of Dorian Gray. New York: Garland Pub.

Leckie, B 2013 ‘The Novel and Censorship in Late-Victorian England.’ The Oxford Handbook of the Victorian Novel, Corby: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199533145.013.0009

Love, H 2009 Feeling Backward: Loss and the Politics of Queer History. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctvjghxr0

McCabe, S 2005 ‘To Be and to Have: The Rise of Queer Historicism,’ GLQ: A Journal of Lesbian and Gay Studies, 11.1, 119–134. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1215/10642684-11-1-119

McGann, J 2001 ‘Radiant Textuality: Literary Studies after the World Wide Web.’ Springer. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-10738-1

McKenzie, D F 1986 Bibliography and the Sociology of Texts. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

McKerrow, R B 1950 Prolegomena for the Oxford Shakespeare: A Study in Editorial Method, Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1939.

Ruddick, N 2003 ‘“The Peculiar Quality of my Genius”: Degeneration, Decadence, and Dorian Gray in 1890–1891.’ Robert N Keane (ed) Oscar Wilde: The Man, His Writings, and His World, New York: AMS Press, 125–137.

Tanselle, T 1989 A Rationale of Textual Criticism, University of Pennsylvania Press.

Thain, M 2016 ‘Perspective: Digitizing the Diary – Experiments in Queer Encoding,’ Journal of Victorian Culture, 21.2, 226–241. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13555502.2016.1156014

The Shelley-Godwin Archive. University of Maryland, College Park. Maryland Institute for Technology in the Humanities (MITH).

Traub, V 2013 ‘The New Unhistoricism in Queer Studies.’ PMLA, 128.1, 21–39. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1632/pmla.2013.128.1.21

Wilde, O 1889–90 MA 883. The Picture of Dorian Gray: Original Manuscript. Morgan Library & Museum, New York, NY.

Wilde, O and Bristow, J 2000 The Complete Works of Oscar Wilde, 3, Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/actrade/9780198119609.book.1

Wilde, O and Frankel, N 2011 The Picture of Dorian Gray: An Annotated, Uncensored Edition. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4159/harvard.9780674068049

Wilde, O and Gillespie, M P 2007 The Picture of Dorian Gray: Authoritative Texts, Backgrounds, Reviews and Reactions, Criticism, 2nd ed., New York, W.W. Norton, 2007.