Introduction

In the late 2010s, menstruation became a topic of mainstream political and policy debate in Scotland.1 Menstruation, the public was told, should not be taboo, talked about in euphemisms, or deemed shameful. Yet paradoxically, menstruation itself remained nowhere to be seen. Despite Scotland’s long history of exploring menstruation in medicine, policy, and, more recently, politics, menstrual blood has remained under wraps there as much as in other countries. As media coverage and public discussion built towards the passing of the Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act into law on 12 January 2021 by the Scottish Government, the wider cultural landscape was characterised by this in/visibility of menstruation.

In order to explore menstruation’s often contradictory and complex status in the 2010s and early 2020s, the authors of this paper collaborated to examine how the University of St Andrews responded to calls for free products before and after the Act, and how this response links to longer histories in menstruation’s in/visibility in both the town of St Andrews and Scotland as a country. Bee Hughes’s artist residency in St Andrews, which occurred before the 2020 strikes called by the University and College Union (UCU), and the emergence of the Covid-19 pandemic in March of that year, relates to their longstanding practice of producing menstrual art. 2 Their work provides a through-line in what follows for analysing the paradox of menstrual in/visibility, from the logistics of implementing the Act’s requirements on the ground, to the wider engagements (or, rather, lack of) in visual art and culture in Scotland which formed the context for the legal framework.

To underline the ways in which menstruation interlinks with other issues, Hughes’s pre-pandemic visit to St Andrews included exploring parts of the town affected by menstrual stigma or policy both historically and recently. This included the University’s Estates team, (which is responsible for cleaning on campus, sanitary bins, and the practical roll-out of the Act), the University Feminist Society and LGBTQIA+ student groups who advocated for free products before the Act and stressed the importance of inclusivity, scholars who research menstruation, the local foodbank and the University’s museums. We observed what types of products were available in the local shops and in campus bathrooms, and Hughes documented their visit through photographs and notes.

Reflecting on these observations, the artist had hoped to make a work of menstrual art, while we collectively began investigating the longer histories, both traceable and occluded, of menstrual art and culture in St Andrews and Scotland. The project was initially conceived in a cyclical model, involving independent work punctuated with regular and collaborative interventions when the artist could be ‘in residence’. However, the UCU strikes and the Covid-19 pandemic put a stop to this plan, and our methodologies shifted in response.3 Against a background of absences of ‘normal’ public life instituted through public health measures, we realigned the project towards the many hidden aspects of menstrual experiences amongst people who menstruate and those who were tasked with implementing the rollout of the Act.

Our collaborative project utilises artistic practice as a way of exploring the specificity of menstruation’s cultural in/visibility. Hughes considered St Andrews a central location for their developing research and practice, having presented and exhibited their work at the University before.4 Building on their existing relationship with the town, Hughes has described their practice as ‘autobiographically entangled’,5 often drawing on autoethnographic methods and ‘performative bricolage’6 to produce works exploring their experiences of menstruation and gender.

The fragmentary nature of the project, and our account of it, reflects a number of the challenges that come with researching menstruation, and with developing and enacting menstruation policy. We acknowledge the rough edges that accompany collaborative and interdisciplinary work, particularly when time and distance are taken into account. We also accept the slippages that can become magnified when working with topics that are at once deeply personal and societally important. The complexity of working with menstrual themes in this way is reflected not only in the broader considerations of menstrual literacy that are needed to enact menstruation policy successfully, but also in the tensions that surface in the production of artwork(s) by one artist, exploring a phenomenon (menstruation) that is experienced in so many varied ways, and impacted by different social and cultural conditions. We are informed by Sara Ahmed’s queer phenomenology7 and her notion of ‘sweaty concepts’, which ‘come[s] out of a description of a body that is not at home in the world … that might come out of a bodily experience that is trying’.8 Though we recognise it is not always possible to reconcile neatly visual art production, our cultural and socio-political present, and our subjective experience(s), this article presents an account of our collaborative distance-working. Referencing Ahmed, this article represents our attempts to weave together our experiences and ‘stay with the difficulty, to keep exploring and exposing this difficulty’, through and with the multiple challenges and changes encountered during the project when the initial goal (the making of a work of art) was no longer possible.9

Reflecting on the changed and disrupted circumstances of this project, in the first section of this article, we situate Hughes’s residency within the specific context of St Andrews as both the university and organisations in the town attempted to implement The Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021. In the second section, we link this to histories of feminist activism in St Andrews, and to the relationship between visual practice and menstruation in Scotland more widely, before we return in the conclusion to the symbolism of the St Andrews red gown, to period poverty, and to visual culture in the context of menstrual (in)visibility (Figure 1).

Our article closes with a first-person perspective by the artist discussing their work in St Andrews and the symbol of the red gown in their initial stages of creative exploration. Given that Scotland is one of the first countries to have made access to free menstrual products legally binding through The Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021, we wanted to address whether there were specific visual cultures that had informed this. Working outward from the particular challenges presented by undertaking a residency when the artist cannot be present, we consider how this might parallel, and provide an important analytical perspective on, the wider issue of menstrual presence and absence in Scotland.

Ending period poverty in St Andrews

The implementation of the Act by the Scottish Government meant a sudden change for anyone tasked with stocking menstrual products in toilets and other facilities around the town. The Act meant that institutions had a duty of care towards any menstruator who might need a product, and therefore included local schools, colleges, the food bank, and the university. Some institutions had to quickly figure out how menstrual products would fit into their overall strategy for the provision of free items, while others expanded their already free menstrual product options.

At the University of St Andrews, as elsewhere, student groups had been increasingly active in the debate around menstruation and access to products. Significantly, university students had been petitioning for free products for years and started a petition for free products in 2018.10 Trans and nonbinary students had also already been foregrounding an inclusive attitude to provision (such as that taken by the Act), insisting on the importance of products being made available in men’s bathrooms, gender neutral toilets, and in toilets for disabled people. This work was typical of many parts of the early End Period Poverty movement in the 2010s, in that it was inspired by an intersectional feminist lens, fronted by young people, and often involved groups working on specific issues who had specific expertise.11

When the roll-out of the Act finally began, however, students like those involved in the Feminist Society also sometimes took on the role of educators. When a small number of other students made transphobic remarks about provision on the Society’s Facebook page, for instance, it was often up to the society members to provide support for trans students. Since limited guidance was available from the government (or from the University itself) regarding the role of gender and menstruation, student groups like these stepped in instead. For trans and non-binary students, and for non-students, this could be both frightening and exhausting. The lack of guidance from institutions around gender inclusivity demonstrates a knowledge gap between grassroots activism and the stakeholders of policy implementation. It also suggests an underlying unfamiliarity with the complex intersectional considerations inherent in advocacy, activism and academic research around menstrual health and experience.12 Much of this labour was not immediately legible to a wider public. While student activism was a substantial part of the menstrual movement in Scotland leading up to the passing of the Act, the particulars of institutional critique and complex labour, like the one undertaken by students at St Andrews, remain largely invisible.

While the students were part of activist work to raise awareness for period poverty, another group has had an even more intimate and long-standing relationship to menstruation and public buildings. At the University, the Estates team are in charge of cleaning and of supplying materials across the sprawling campus, which is spread throughout the town. For this group, the Act meant new practical challenges. While the Act offered some advice for such teams on how to acquire products, store them, and to promote the scheme, cleaners had to take a creative and space-specific approach to every single room, as each building and toilet on an old campus like St Andrews was necessarily slightly different.13 Furthermore, the Act gave room for Estates teams to purchase products from a list of providers, notably regarding decisions about reusable versus non-reusable products. But as reusables are more expensive than single-use options (at least in the short term), this was also a decision connected to the overarching economic decision-making powers at the institution. In these ways, Estates had both flexibility and limitations when implementing the Act, including the power to make reusable options visible in the university community within certain economic boundaries.

Tracing notions of invisible and visible menstruation, we noted that the Estates team likely had the most knowledge about the everyday realities of menstruation in the workplace, and had expertise in discussing and managing menstrual practicalities. The Act made their existing work more visible to other colleagues and necessitated more discussion about menstruation throughout campus. These discussions, however, often centred on products, waste, disposal systems, and cleaning, which linked menstruation to long-standing historical tropes about menstrual blood being ‘unsanitary’ or a ‘hygiene’ issue.14

It took some tweaking by the Estates team, but ultimately systems that took into account all the compromises (regarding, for example, access, finances, the environment, disposal, and gender) were established. For example, in the Student Union, students had to ask for products at the reception desk, where a box of disposable tampons and pads was provided. In staff-dominated buildings, products were not consistently available apart from some staff-organised and donated products. In the University Library and public areas, the vending machines filled with Tampax and Always tampons and pads (both brands produced by Procter & Gamble) simply became free overnight. However, conversations about how best to manage the presentation and dissemination of menstrual cups and reusable pads on campus are ongoing.15

While students and the University as an institution were able to rely on the experienced Estates team to roll out the Act, infrastructure also existed at the St Andrews food bank. Organised by the neo-charismatic evangelical Christian Kingdom Vineyard group inside the Holy Trinity Church building in St Andrews, the service (called Storehouse) is open to anyone who needs it and is run through the Fair Share food distribution centre in Scotland. Structurally, menstrual products had been added to Fair Share’s existing regular delivery (nearby supermarkets supplemented this on an ad hoc basis, and community members sometimes dropped off donations). As we saw in other settings, the food bank had to rely on their own knowledge of consumers and of the architecture of the building (an old church) to process the change. When the Covid-19 pandemic began, the service continued for as long as it could. As shops and other options became impossible to reach due to a government-mandated stay-at-home order, the food bank’s inclusion of menstrual products was likely more important than ever imagined. Here, we note that the invisible labour of food banks became more public during the pandemic, and that because of the Act, menstrual products were already part of this labour.

Our observations of menstrual visibility and invisibility in St Andrews underline the ways in which some menstrual debates remain hidden. Most of the labour surrounding menstruation, including cleaning and providing products in bathrooms and foodbanks, continues to be discreetly done and is in many respects made invisible.16 The activism undertaken by students for equal access to bathrooms and products was highly visible for a time, but merged with the larger and national period poverty movement once policy-makers and politicians intervened. Encountering these examples, we began to understand the underlying tapestry of menstrual stigma in St Andrews which still exists, despite some menstrual topics becoming more public. Since visual art can make some of these invisible strands of discourse visible, Hughes will include these examples in their future studio work for this project.

Menstruation, Feminist Activism in St Andrews and Art Practice

Having explored contemporary menstrual visibility in St Andrews, we turned to history to understand how the longer traditions of activism, feminism, and reproductive justice debates in St Andrews might have contributed to where we are today. Throughout the modern history of St Andrews (and in higher education more generally), menstruation tended to be present only as subtext, but it has still shaped the lives of people in the town. Second Wave feminists fought against essentialist views of the body and argued for more access to public space.17 Today’s students face some of the same challenges, such as questioning the role of gender identification, particularly in relation to bathrooms. This activism is similar to the work of challenging menstrual stigma: it is a process of unpicking and undoing decades and centuries of assumptions about the student body, the student’s body, and the body of the town itself.

While St Andrews has a reputation as a conservative town, it also holds a long history of radical feminist activism. Historian Sarah Browne’s work on 1970s Second Wave feminism in Scotland uniquely positions St Andrews in this history as ‘a veritable hotbed of feminism’, fuelled in part by the international student body.18 Part of this work was about reproductive justice, with critiques of lectures at the University that stated untruths about women, biology, or gender, as frequently discussed in the Women’s Liberation Movement’s newsletter Spare Tyre (whose title references the more famous British feminist magazine Spare Rib).19 Fighting against a strong current of moralistic and traditional views about women in the community, feminism emboldened some students to think of themselves as part of a historic trajectory stretching back to the suffragettes and the first generation of women students and staff, while anticipating an unknown future where new student bodies would look more balanced.20

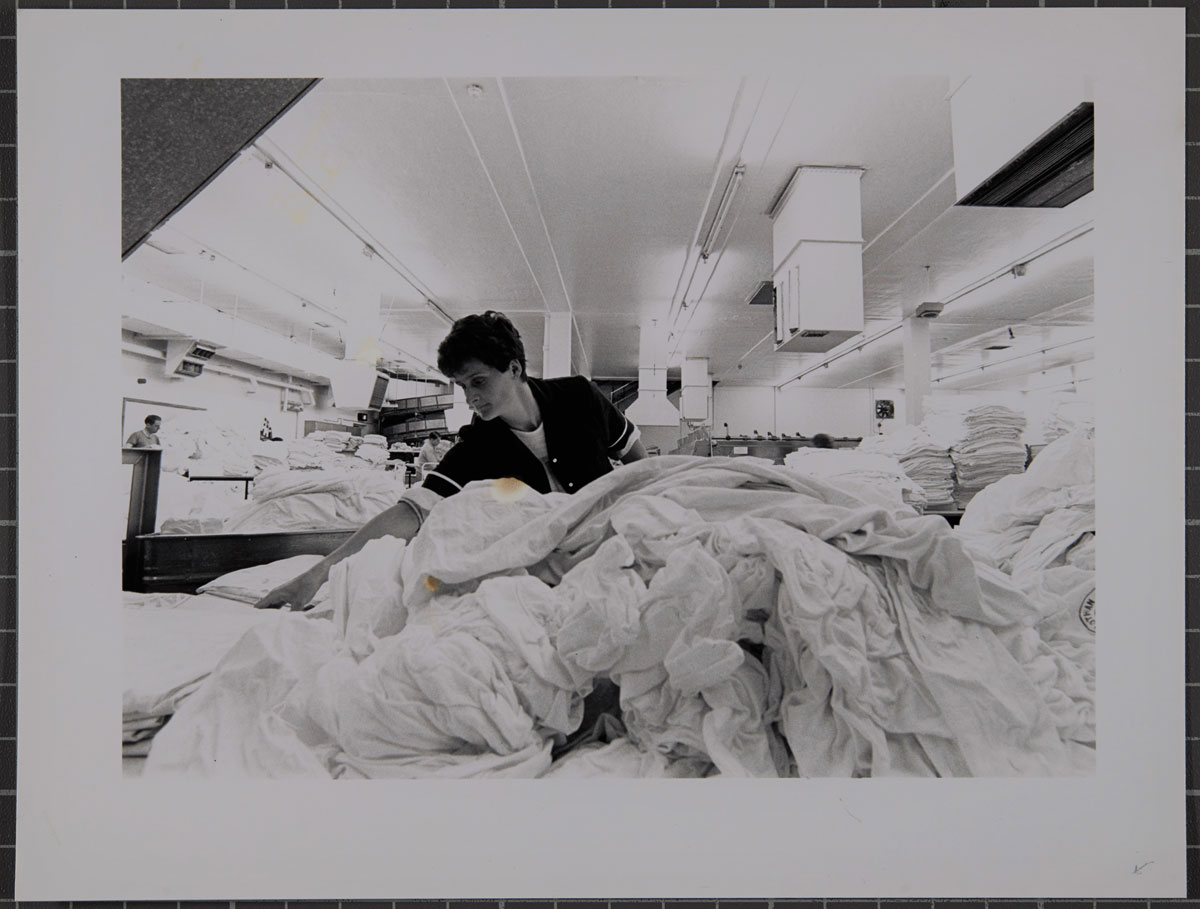

The Women’s Liberation group in St Andrews utilised many tactics to make space for itself, and to become visible in a larger battle for access to public, social and educational spaces for women. They vandalised the men-only golf course grass, harassed men on the street by staring at them and catcalling, and protested the mocking of female students that occurred during the annual Kate Kennedy parade in which a male student dresses as a woman.21 Their activism often also included aspects of art. For example, a day out in Aberdeen was organised around the group’s wishes to visit and vandalise sexist artworks in a local gallery, and several members were also practicing artists or would go on to be so, such as textile artist Anne Jackson.22 Feminist documentary photographer Franki Raffles, whose archive Hughes consulted during their visit, is a prominent example. Raffles studied Philosophy at St Andrews and was active in the Women’s Liberation group there. After graduating she moved to Edinburgh and, during the 1980s and early 1990s, started a photographic practice which was particularly concerned with representations of working women.23 One of the last projects that Raffles worked on before her untimely death in 1994 was a commission by NHS Lothian titled The NHS: A Healthy Place to Work and Live.24 As part of this project, Raffles photographed women workers, staff, families, patients and carers across hospitals, clinics and GP surgeries. In these images, the profound ways in which (waged and unwaged) labour and care are intertwined in the daily lives of many women are articulated from a feminist perspective, which demonstrates how histories of feminism and health are fundamentally combined. While not directly engaging with menstruation, Raffles’s early interest in the work of women can be seen as an effort to visualise hidden and undervalued aspects of ‘women’s work’, such as washing dirty linen and cleaning offices.

Through their art, performances and stunts, the St Andrews Women’s Liberation group sought to bring attention to sexism, particularly sexism related to essentialist views of gender and women’s places in the physical and intellectual world. Their critique of Biology lectures demonstrates the group’s acute awareness of how discussions about women’s bodies could be weaponised against them. The group continued to question and fight against essentialist views of the body throughout the 1970s, before its members dispersed across the world.

The creativity of the St Andrews Women’s Liberation group, and of Raffles’s body of work in particular, intersects with the wider relationship between visual art and feminist activism in Scotland, including artistic and theatrical engagements with menstruation. Examples from the late 20th century show how artists working in Scotland linked menstruation to themes of growing up, girlhood, and sex, amongst other themes. These vary in medium, including a play, a performance art piece and zines, as well as in the reactions they incited, which ranged from outrage to critical acclaim to investigation and counter-cultural dissemination. On the opening night of Scottish playwright Sharman Macdonald’s first play about girlhood and sexuality, When I Was A Girl I Used to Scream and Shout, for instance, 13 people walked out. Performed in September 1991 at Dundee Repertory Theatre, the show began with three teenage girls trying to make sense of adulthood, addressing topics including menstruation. The play’s reception varied from outrage to celebration, and it was praised for being ‘beautifully written and acted’ in The Sunday Times.25 The critical success of Macdonald’s play was one indication that attitudes to discussing sexuality and menstruation were changing in Scotland, and that writers and visual artists were seeking to foreground and investigate these themes in their work. Macdonald’s play nonetheless remains an arguably atypical instance of overt reference to menstruation in visual and literary cultural production in Scotland during the 1990s.

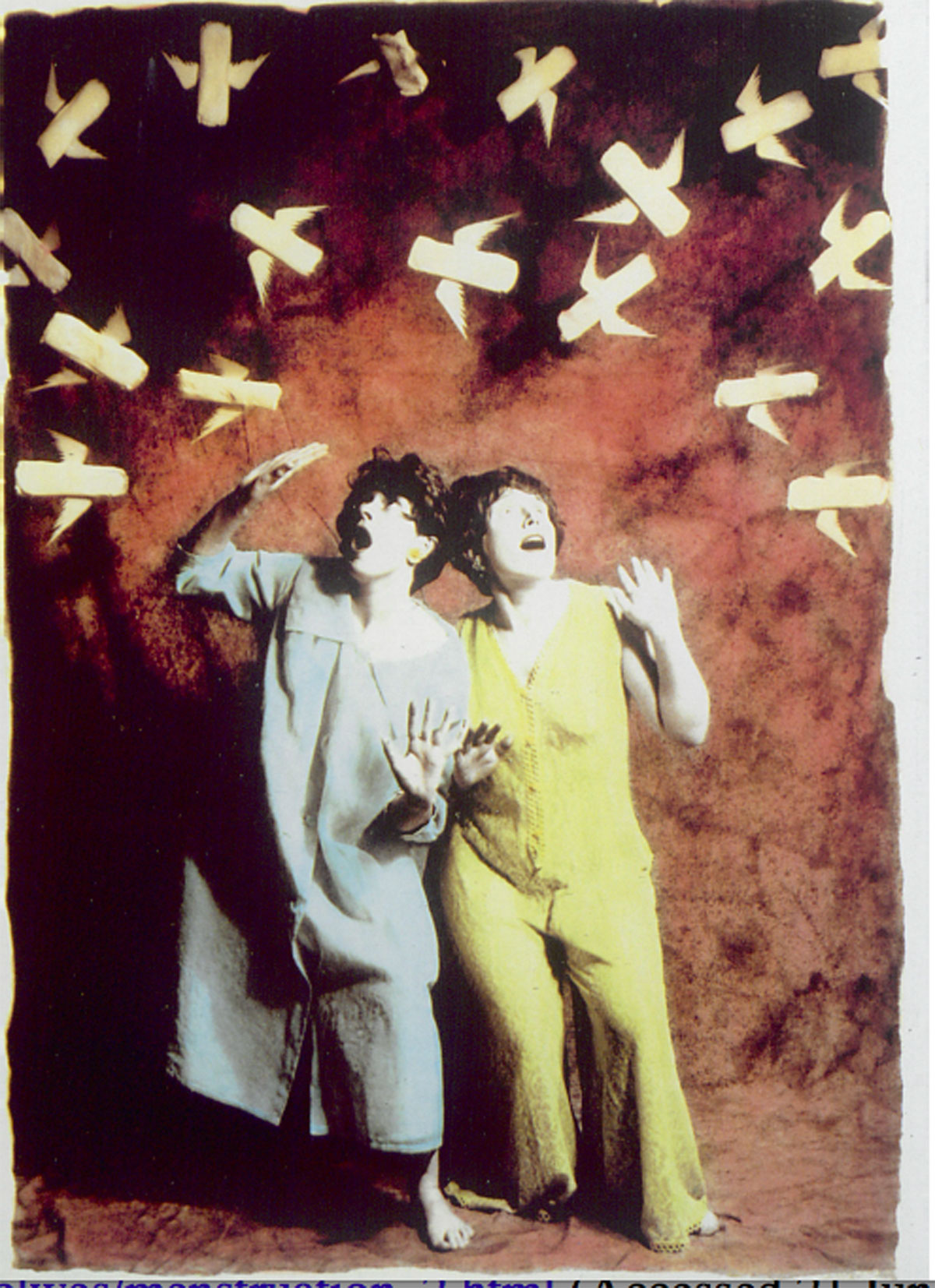

LGBTQIA+ and feminist magazines circulating in Scotland also poked fun at menstrual tropes, exemplified by the humour and creativity in Megan Radclyffe’s collage Napkin Neurosis, where pads fly across the room like scary angels (Figure 2).

The Glasgow Women’s Library’s Zine Library holds multiple menstruation-themed zines, including unique items made by comic book artist and musician Zaskia in the 1990s. She published a series of menstruation-themed zines named Heavy Flow to chronicle her own interest in the topic, as well as a growing political and feminist awareness of menstrual issues in Scotland.26 However, although we looked in Scotland for examples of the feminist menstrual art produced elsewhere in the UK, particularly during the 1970s, we could not find evidence of this.27 It does not seem that there was an equivalent in Scotland for the work of practitioners like Catherine Elwes, notably her performances Menstruation I and Menstruation II in the Slade School of Art in London in 1979, during which she enclosed herself in a white room and visibly menstruated over several days.28 The wider retreat across the UK from these forms of expression might be mapped onto the resurgence of cultural conservatism in Britain and Scotland during the 1980s, together with the fragmentation of the Women’s Liberation Movement and associated feminist art activity. Before the debut of Macdonald’s When I Was A Girl I Used to Scream and Shout, in 1988 the US performance artist Karen Finley’s work Constant State of Desire, which also included frank menstrual themes, had been banned in the UK and was subject to an investigation by Scotland Yard, suggesting a tightening of what was deemed admissible in terms of social acceptance when it came to periods (and/or a fear of more visible representation in the future).29

These ebbing and flowing histories of art and menstruation in Scotland and in the UK more broadly demonstrate the wider context of our project, and our desire to look in particular at how art practice might provide a way of highlighting the little-known histories of menstrual activism and engagement in St Andrews specifically. These examples are reminders of a long-interlinked history of the arts, menstrual themes, and the public. Hughes’s work at St Andrews thus constitutes only one of the most recent contributions to this artist-activist discourse, which we hope illuminates how visual production and its reception can help us to understand changing attitudes to menstruation in Scotland today.

The Artist is Not Present (a First-Person Account)

In this section, Hughes reflects on their experiences of working with the subject of menstruation, of St Andrews, of walking the line between being an academic and an artist, and of the role of (their) art in the conversations around The Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021. This section is written in the first person: a change from the previous sections, reflecting the tension that surfaces within this article (and in menstrual activism and advocacy more broadly) between the personal and the collective.

St Andrews is significant to my practice as a menstruation researcher and artist working with menstrual subject matter, as it is the first place where I presented this body of work to my peers. The town and university have been instrumental in shaping my understanding of the field, through various visits in support of Menstruation Research Network UK activities (a Wellcome Trust supported network of menstrual scholars active from 2019 onwards), the exhibition of my work in the Cloisters of the University’s St Salvator’s Chapel, and the collection of that work by the Museum of the University of St Andrews. Since visiting in 2018 I have felt an affinity to the town. It reminds me of home in elements of its geography, historic architecture, and the sense of division that bubbled underneath the surface. I grew up in rural North Wales, near the coast, the mountains of Snowdonia, and the university city of Bangor.

St Andrews is a small town on the east coast of the region Fife, with a population of about 17,000. It is home to one university, established in 1413 and considered a high-ranking academic institution. There is a palpable split between the university in St Andrews and the wider town, which also encompasses golf courses, a small fishing community, agriculture, a hospital, shops, a botanical garden and museums. Its reputation, alongside that of the university, is one of prosperity, privilege and conservativism, and it is steeped in long-standing traditions, student societies and systems.

During my first visit as artist in residence in 2020, we began considering what symbols of St Andrews might be available to act as an anchor for the creative work, a material grounding to situate a practice in and with the town and university. My curiosity was piqued by recalling glimpses of figures around the campus dressed in red gowns, the University of St Andrews’s ceremonial attire. Since 1800, students at the University have dressed in bright red gowns and walked back and forth over a harbour pier to commemorate the rescue of crew members of the ship Janet Macduff by a former student. The red garment is one of the most well-known markers of the institution and has a long history of public wear. Since its introduction during the post-Reformation era as a compulsory ‘school uniform’ for youngsters to prevent them from drinking in pubs, the gown has become an icon of the town.30

As an artist who explores the social and cultural aspects of menstruation in their art and academic works, I noted that the gown could be re-appropriated as part of this project as a symbol for menstrual invisibility and visibility. While the bright red gown is on public display every week as students walk the pier and circulate in the small town (as well as during graduation and formal events), menstrual signs remain taboo and occluded. The identification and re-appropriation of this symbol was important creatively and conceptually. As an artist, I do not see my role as (re)interpreting the findings of my collaborators (or even my own research data) into an artwork. My aim is not to represent the conversations Camilla, Catherine and myself had literally or figuratively in St Andrews, nor is it to quantify the impact of the Act. Rather, I see my role as an artist in residence (or elsewhere) as trying to navigate the various discourses of menstruation circulating in a particular cultural milieu, to form impressions, and to bring together fragments from these layered observations. My aim is not to hold up a mirror and produce a straightforward reflection, but to highlight contradictions, stitch together fragments, and produce objects or performances in dialogue with the space(s), experiences, and ideas encountered.

The hypervisibility of the red gown in St Andrews linked to our shared central concern with the ways in which menstrual visual cultural production, and specifically menstrual art that utilises real blood, have informed and shaped menstrual culture and discourse in Scotland and beyond.31 My plan was to re-appropriate the gown as a menstrual symbol (Figure 3).

Re-appropriation and fragmentation have been a central theme in my art practice in recent years, particularly using cut-up text and autobiographical elements to foreground the limited space for gender-diverse experience in medical and everyday framings of menstruation.32 These works also aim to counter explicitly the historic absence of menstruation in everyday life in the UK, characterised by Victoria Newton as ‘a historical shift from the invisible menstruating woman to invisible menstruation’.33 While political and public discourses have moved towards vocalising (and making visible) menstrual products as a key component of gender and economic social justice, the turn towards menstrual management as a panacea has continued to maintain the invisibility of menstruation itself. Though period products are now part of mainstream discourse, menstruation itself (with its visceral, inconvenient, affirming and contradictory materiality) remains absent, as does the labour of those who make the provision of menstrual products possible.

With only one official visit under my belt for this project, and the second in March 2020 cancelled due to a strike (which myself and my co-authors supported) and due to the worsening international news about Covid-19 (and the eventual ‘lockdown’), my preliminary notions about a co-produced, participatory, performance-led work were thrown into disarray. Instead, we turned to the historic documentation that we explored during my first visit, especially the photographic archive of Raffles held in the University’s Special Collections. This rooted me somewhat in the rhythms of the town, and the history of feminist health activism in Scotland documented by Raffles in the 1980s and early 1990s.

I was particularly struck by Raffles’ photographs documenting the everyday work and workers of hospitals in the Lothian region. Western General Hospital Laundry (1993) (Figure 4) in particular, with the billowing piles of cloth and neatly folded stacks of crisp white linens, brought to mind the contrast between the clinical and hygienic practices of medicine (and menstrual self-care) and the sometimes messy realities of medical treatment and the leaky menstruating body.

Washing and keeping the body clean has so often been considered ‘women’s work’, and in Raffles’s documentation we see a respectful portrait of this hidden labour and gendered pressure.

The first visit offered unique insights into the contemporary and historic contexts of St Andrews, making me excited to unravel further the story of menstruation in the town. This enthusiasm was challenged during the strike and pandemic, which left the project uncertain, and the threads I had gathered in January slipping through my fingers. As I adjusted to thinking about the project and St Andrews from afar, the need for a physical connection to anchor my creative practice became evident: enter the red gown. I purchased a red gown of my own, had it shipped to my home, and started exploring its components (Figures 5 and 6).

As I got to know the gown’s material and details, I began reflecting on the prevalence of the gown in the university’s marketing materials: for example, a photograph of the pier procession on campus maps, and splashed across the university’s website. The consistent presence of the gown in the University of St Andrews’ collective identity became solidified as a significant symbol, which could be re-formed around the role of Scottish universities in this historic moment for menstrual equity. At the same time, the ‘lockdown’ meant that no-one was walking the piers in St Andrews anymore, that the gown was back in the closet, and that the ambitious Scottish period poverty plan would be tested in ways unforeseen by policy makers.

The Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act 2021 was necessitated by the need to grapple with economic inequalities in Scotland. The pandemic only underscored this. Likewise, our symbolic gown also documented a history of privilege and financial exclusion in St Andrews through its price and manufacturer. For months, we tried to find out where the gowns were made, by whom, and how. After numerous emails and phone calls, the makers of the gowns, leading UK academic gown providers Ede & Ravenscroft, replied after we were vetted through a University of St Andrews retail connection. They told us that the gowns were made in Littleport in England, and constructed of dyed wool and velveteen. The reason for the secrecy was financial and legal. A few years prior, a new academic dress company tried to make the red gowns cheaper and more accessible. This led to a lawsuit with Ede & Ravenscroft, who argued that no-one else had the right or ability to make the red gowns as well as they did.34 Ede & Ravenscroft gowns are today sold for £159, whereas competitor Churchill Gowns slashed this to £89. The lawsuit continues, while the gowns are still being sold and worn by new generations of St Andrews students. This financial background was interesting to us as part of unpicking the privilege, economic realities, and creation of the gown itself. Furthermore, it seemed to echo the conversation around menstrual products: are they a necessity that should be free (like toilet paper) or a luxury? Should institutions provide or subsidise these items, or is it up to the individual to acquire the necessary funds? At a moment when menstrual products became free in Scotland, the gowns remained inaccessible to many. Arguably, both items are needed for anyone to appear as a St Andrews student: the menstrual product to avoid leaking and embarrassment, and the gown to be a part of the elite intellectual academic community.

These were the beginnings of my project to re-make the red gown, to un-pick and cut up its association with academic prestige, and to create a new link with menstrual work. The gown itself, a heavy wool garment covering the body from the shoulders to the calf, simultaneously marks the wearer as part of this academic community whilst shrouding the body beneath its voluminous folds (Figure 7).

This dichotomy, hypervisible yet hidden, called to mind the strands of presence and absence inherent in menstruation research, experience, visual cultures, and policy-making. The gown itself became the site of my artistic exploration as I set about devising a process of making that mirrored the processes and themes uncovered by my first research visit.

I resolved to unpick and undo the gown, document its various threads, the panels of wool and velveteen, and the hidden supporting structures within the garment, in order to re-make them as symbols of menstruation (Figure 8).

The gown was never intended to symbolise menstruation. Indeed, the very fabric of centuries of academic life has been built around the Cartesian notion of an immaterial intellectual self: the body is obscured, even denied, in favour of intellectual authority. Herein I find the humour and significance in dragging it into conversations about menstruation, of entwining it with the public, private, political, and academic discourses around fleshy, leaky bodies of people who menstruate, and how to support them (Figure 9).

Conclusions: Making Menstruation Visible?

As Scotland combats period poverty, the gown is a reminder of underlying economic inequalities. While the lawsuit of the gown manufacturers continues in the courts, the episode clarifies how the gowns also tie St Andrews to an economic history of privileged access to the paraphernalia of studenthood. Not all students can afford the gown, and, as we know, some also utilise the foodbank. Some students thus welcomed the alternative, cheaper gown, excited finally to be able to access the proper academic ‘look’, wrapped in red and visible to the world. In what is often assumed to be a privileged space, like St Andrews, Scotland, or the Global North, it is easy to focus on status symbols such as the red gown or a generous menstrual product policy. The underlying issues, whether poverty or stigma, will likely not dissipate through a singular focus on pads, cups and tampons. Like menstrual products, the economic fight around the red gowns benefits companies first and foremost. Whether gowns are sold by Ede & Ravenscroft or Churchill Gowns, and menstrual products are supplied through the Scottish government or vending machines, a red-hot economic market serves no one better than the supplier.

Today’s students, cleaners, foodbanks, academics, and citizens are making the menstrual subtext into text in St Andrews. Menstruation is no longer so invisible in the town, nor is it in Scotland. The country has housed menstrual research and policy development, provided free products to all, and fronted a national campaign calling for an end to all menstrual euphemism: ‘Let’s call periods, periods!’35 We hope that our project contributes to and amplifies the various moments where menstruation has ‘bled through’ into the foreground of public life in the town and beyond. As the subtext becomes clearly articulated text, a new future beckons for those who menstruate in St Andrews: one in which products are more readily available, and where discussions about menstrual pain, health, and pleasure are not far behind.

Notes

- Fiona McKay, ‘Scotland and Period Poverty: A case study of media and political agenda setting’, in James Morrison, Jen Birks, Mike Berry (eds.), Routledge Companion to Political Journalism (London: Routledge, forthcoming 2022). [^]

- For an initial reflection see Bee Hughes, Camilla Mørk Røstvik and Catherine Spencer, ‘Blood Lines: Researching Menstrual Histories During a Pandemic,’ 17 February 2021, https://centreforcontemporaryart.wp.st-andrews.ac.uk/2021/02/17/blood-lines-researching-menstrual-histories-during-a-pandemic/ (Accessed 16 November 2021). [^]

- In February 2020, the University and College Union (UCU) announced 14 days of strike action as part of a long-running dispute over pensions and a platform known as the Four Fights (casualisation, equality, pay, and workload): https://www.ucu.org.uk/article/10621/UCU-announces-14-strike-days-at-74-UK-universities-in-February-and-March (Accessed 16 November 2021). In mid-March 2021, the University of St Andrews reported its first case of Covid-19 and university buildings closed shortly after. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-edinburgh-east-fife-51872202 (Accessed 16 November 2021). [^]

- Bee Hughes, Dys-men-o-rrho-ea, 2019. Photographs of private performance at Liverpool School of Art & Design. St Andrews collection: https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/item/dys-men-o-rrho-ea/1022104/viewer#?#viewer&c=&m=&s=&cv=&xywh=-829%2C-103%2C3901%2C2059; Bee Hughes, Incomplete Cycles (December), 2016–2017. Digital collage containing daily body prints. St Andrews collection: https://collections.st-andrews.ac.uk/item/incomplete-cycles-december-3rd-edition/1022103 [^]

- Bee Hughes, ‘Challenging Menstrual Norms in Online Medical Advice: Deconstructing Stigma through Entangled Art Practice’, Feminist Encounters: A Journal of Critical Studies in Culture and Politics 2, no. 2 (2018): 15. [^]

- Dallas J. Baker, ‘Queering Practice-Led Research: Subjectivity, Performative Research and the Creative Arts’, Creative Industries Journal, 4 no. 1 (2011): 33–51. [^]

- See Sara Ahmed, Queer Phenomenology: Orientations, Objects, Others (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2006). [^]

- Sara Ahmed, Living a Feminist Life (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2017), 13. [^]

- Ibid. [^]

- ‘Free Sanitary Products at the University of St Andrews’, change.org (2018): https://www.change.org/p/university-of-st-andrews-free-sanitary-products-at-the-university-of-st-andrews (accessed 19 January 2022). The petition was signed by 559 people before momentum slowed as the official Scottish government response appeared later that year. [^]

- In the UK, this work was led by many individuals, groups and charities, including the Red Box Project, Bloody Good Period, Chella Quint and Period Positive, and the social enterprise Hey Girls. However, the schoolgirl Amika George led one of the larger campaigns and street protests to End Period Poverty during the 2010s in the UK, initiated by her change.org petition in 2017 and the associated social media campaign #FreePeriod. [^]

- Sarah E. Frank, ‘Queering Menstruation: Trans and Non-Binary Identity and Body Politics’, Sociological Inquiry 90, no. 2 (2020): 371–404. [^]

- Access to Sanitary Products Aberdeen Pilot: Evaluation Report (Housing and Social Justice Directorate, 30 May 2018): https://www.gov.scot/publications/access-sanitary-products-aberdeen-pilot-evaluation-report/ (accessed 7 February 2022). [^]

- On the history of the sanitary bin and the development of sanitary waste disposal systems in Britain, see Camilla Mørk Røstvik, ‘“Do Not Flush Feminine Products!” The Environmental History, Biohazards and Norms Contained in the UK Sanitary Bin Industry Since 1960’, Environment & History 27, no. 4 (2021): 549–79. [^]

- Our observations about where products were available on campus were based on pre-pandemic visits. [^]

- Scholars have explored the invisible nature of socially reproductive labour: see, for instance, Tithi Bhattacharya (ed.) Social Reproduction Theory: Remapping Class, Recentring Oppression (London: Pluto Press, 2017); Louise Toupin, Wages for Housework: The History of an International Feminist Movement, 1972–1977 (London: Pluto Press, 2018); Kathi Weeks, The Problem with Work: Feminism, Marxism, Antiwork Politics, and Postwork Imaginaries (Durham, NC and London: Duke University Press, 2011). [^]

- See Sarah Browne, ‘“A Veritable Hotbed of Feminism”: Women’s Liberation in St Andrews, Scotland, c.1968–c.1979’, Twentieth Century British History 23, no. 1 (March 2012): 100–123. [^]

- Browne, ‘“A Veritable Hotbed of Feminism”, 100–123. [^]

- Browne, ‘“A Veritable Hotbed of Feminism”’, 107. [^]

- On feminism in Scotland see Esther Breitenbach and Fiona Mackay, eds. Women and Contemporary Scottish Politics: An Anthology (Edinburgh: Polygon at Edinburgh, 2001) and Henderson, Shirley, and Alison Mackay, eds. Grit and Diamonds: Women in Scotland Making History, 1980–1990 (Edinburgh: Stramullion, 1990). [^]

- The Kate Kennedy parade continues to be organised every year. It has been implicated in recent reporting on harassment at the University of St Andrews: Marc Horne, ‘St Andrews Sex Scandal Spreads to Elite Society’, The Times (12 August 2020): https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/st-andrews-sex-scandal-spreads-to-elite-society-zztcwkr3h (accessed 7 February 2022). [^]

- Browne, ‘“A Veritable Hotbed of Feminism”’, 119. Jackson’s website: https://www.annejackson.co.uk/ (accessed 10 January 2022). [^]

- The University of St Andrews Photographic Special Collections now holds the Franki Raffles Photographic Archive, which contains over 40,000 negatives of photographs. These explore women’s health, among other topics, and constitute a significant resource for feminist research. For an overview of Raffles’s career drawing on research in this archive, which articulates how Raffles’s commitment to feminism throughout her practice grew from her experience of student activism at St Andrews, see Marine Benoit-Blain, ‘Franki Raffles, photographe engagée: la photographie féministe en Écosse dans les années 1980 et 1990’, Les cahiers de l’Ecole du Louvre, no. 10 (2017): https://cel.revues.org/555 (Accessed 14 June 2017). See also Weitian Liu, ‘Franki Raffles: Photography as a Social Practice’, Photomonitor (March 2021): https://photomonitor.co.uk/essay/franki-raffles-photography-as-a-social-practice/ (Accessed 22 December 2021). [^]

- Alistair Scott, ‘Rediscovering Feminist Photographer Franki Raffles’ Studies in Photography, (2017): https://www.napier.ac.uk/~/media/worktribe/output-969828/rediscovering-feminist-photographer-frank-raffles.pdf (Accessed 28 June 2021). [^]

- ‘Bold Dundee screams and shouts for more money’, The Sunday Times (22 September 1991). [^]

- Helena Neimann Erikstrup and Camilla Mørk Røstvik, ‘Menstruation in the 1990s: Feminist Resistance in Saskia’s Heavy Flow Zine’, Nursing Clio, 7 August 2018, https://nursingclio.org/2018/08/07/menstruation-in-the-1990s-feminist-resistance-in-saskias-heavy-flow-zine/ (Accessed 28 June 2021). [^]

- The intriguing question of whether there was a feminist art movement as such in Scotland during the 1970s cannot be addressed in this article. It is notable that examples of collective and concertedly feminist artistic activity seem to occur later, such as the founding of Women in Profile in 1990 (which ultimately led to the founding of the Glasgow Women’s Library), and which developed the Castlemilk Womanhouse project in 1991, which was based on the early-1970s Womanhouse in Los Angeles. Whereas the Los Angeles Womanhouse featured a ‘menstrual bathroom’, however, the Castlemilk Womanhouse did not. See Hannah Hamblin, ‘Los Angeles, 1972/Glasgow, 1990: A Report on Castlemilk Womanhouse’ in Feminism and Art History Now: Radical Critiques of Theory and Practice, edited by Victoria Horne and Lara Perry (London: I. B. Tauris, 2017), 164–82. For an analysis of Judy Chicago’s menstrual artwork, which includes the menstrual bathroom, see Camilla Mørk Røstvik, ‘Blood Works: Judy Chicago and Menstrual Art since 1970’, Oxford Art Journal 42, no. 3 (2019): 335–53. [^]

- See https://www.luxonline.org.uk/artists/catherine_elwes/menstruation_1.html and https://www.luxonline.org.uk/artists/catherine_elwes/menstruation_2.html (Accessed 21 June 2021). For a history of feminist art in Britain, which situates Elwes’s work in its wider context, see Kathy Battista, Renegotiating the Body: Feminist Art in 1970s London (London: I. B. Tauris, 2013). [^]

- ‘Art at the Outer Limits; Karen Finley, Taking Performance to a New Level’, The Washington Post (4 May 1988). For a longer history of censorship in Britain with regard to art that included references to menstruation, see Siona Wilson’s discussion of the music and performance art collective COUM Transmissions (active 1969–1976 in the UK) in Siona Wilson, Art Labor, Sex Politics: Feminist Effects in 1970s British Art and Performance (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2015), 93–137. [^]

- ‘Academic Dress’, University of St Andrews website (2021): https://www.st-andrews.ac.uk/orientation/once-you-arrive/academic-dress/ (accessed 7 February 2022). [^]

- Art historical investigations of menstruation include Ruth Green-Cole, ‘Painting Blood: Visualizing Menstrual Blood in Art’ in Bobel et al. (eds.), The Palgrave Handbook of Critical Menstrual Studies (Palgrave, 2020), pp. 787-801; Jen Lewis, Widening the Cycle: A Menstrual Cycle & Reproductive Justice Art Show (blurb, 2015); Røstvik and Bee Hughes, ‘Menstruation in Art and Visual Culture’ in The International Encyclopaedia of Gender, Media, and Communication (Wiley, 2020); Carli Coetzee, Written Under the Skin: Blood and Intergenerational Memory in South Africa (Boydell & Brewer, 2019). [^]

- B. Hughes, Performing Periods: Challenging Menstrual Normativity Through Art Practice, Doctoral Thesis, Liverpool John Moores University (2020). [^]

- V. Newton, Everyday Discourses of Menstruation: Cultural and Social Perspectives (London: Palgrave, 2016), 183. [^]

- Margaret Taylor, ‘Fight over St Andrews gowns Hots up as Replica Firm Makes New Legal Case’, The Herald Scotland (20 November 2019): https://www.heraldscotland.com/business_hq/18046894.fight-st-andrews-gowns-hots-replica-firm-makes-new-legal-claim/ (accessed 7 February 2022). [^]

- ‘Let’s call periods, periods’, Scottish Government website (20 January 2020): https://www.gov.scot/news/lets-call-periods-periods/ (accessed 19 January 2022). [^]

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the University of St Andrews, the University Estates team, the University Feminist Society and LGBTQIA+ student group, Kingdom Vineyard church, University of St Andrews Special Collection, Proquest, the two anonymous peer reviewers, and the editors.

Competing Interests

Camilla Mørk Røstvik’s involvement as an editor of this volume has not led to a conflict of interests as the author has been kept entirely separate from the peer review process for this article. The other authors have no competing interests to declare.