Introduction

‘Symbolic domination is something you absorb like air…it is everywhere and nowhere, and to escape from that is very difficult’

Pierre Bourdieu (Bourdieu and Eagleton, 1992)

1989. I’m at a party in California, high up in the Berkeley hills. A sprawling ranch house, a vast and elaborate buffet, valets for the cars, plenty and privilege. An accidental romance has turned serious and I am socialising outside my usual, more bohemian milieu. Here the men appear bullishly confident, the women polished and poised. The host, an avuncular patriarch who made his fortune in household goods, looms over me. ‘Great you could come!’ he says, ‘X tells me you’re writing a book! How exciting.’ He leans in, smiling, ‘What’s it about?’ I’m not used to talking about my topic in this kind of situation, and unthinkingly I say, with no warning preamble or euphemism, ‘It’s about menstruation.’ For the first time I really understand what is meant by someone blanching. His tanned, overfed face literally turns white. He looks at me as if I have broken his heart, turns around and walks away. Oh shoot, I think, I can’t even say the word.

Such a visceral response towards menstruation being openly articulated outside of a medical or countercultural context should perhaps not have been that surprising to me. Over time, the rejections would become more complex, and the stakes would get higher.

1991. I have an article published in a magazine, an extract from the book I am writing. An editor at a prestigious New York publishing house reads it and calls me up to ask if I have a publisher yet. I don’t, and quickly find myself in first-time author dreamland. We are just about to sign the contract when a female executive puts a stop to it, saying, ‘There is no way we are publishing a book that highlights menstruation. It would put back the progress of feminism by a hundred years.’ I understand the role of internalised misogyny in keeping menstruation hidden, in ‘protecting’ women from shame. But still, I am shocked by her certainty and fear, and not least by the sudden block to my research being published.

I have come across this same idea—that women are more protected by menstruation staying in the shadows than by talking about it—many times since, most recently when doing research on menstruation in the workplace (Owen, 2018). Menstruation has been so thoroughly stigmatised (e.g. de Beauvoir, 1953; Douglas, 1966; Johnston-Robledo and Chrisler, 2013) through a variety of strategies cross-culturally (Buckley and Gottlieb, 1988) to the extent that ignorance is widespread (Chrisler, 2013) and many cannot conceive of a culture safe enough to move past normative silencing and marginalisation (Young, 2005; Pascoe, 2007; Vostral, 2008). Such intransigent stigmatisation has affected a wide swathe of experience that includes menstruation being under-researched across disciplines and affecting the career paths of menstrual researchers (Chrisler et al., 2011). I set out to discover the impact of such stigmatisation on the professional lives of menstrual researchers within the context of a changing cultural landscape of menstrual norms and as part of a joint project on the politics of menstruation in Scotland.

Context

Stigma in academia

There are other topics and disciplines in which scholars experience more-than-usual difficulty in their careers due to stigmatisation, such as those working in the fields of race and gender, in areas of medicine such as psychiatric and sexually transmitted illnesses, and on other topics directly related to female embodiment such as abortion, infertility, and menopause. But research on such second-hand stigma is even harder to find than on stigmatised topics themselves. ‘Courtesy stigma’, the term for the associative stigma experienced by family and friends of stigmatised individuals, has been evidenced in several studies (e.g., Goffman, 1963; Page, 1985; Hinshaw, 2005), but the extent to which this also affects professionals is unclear. In the field of education, Broomhead, while researching teachers of children with behavioural difficulties, observed that ‘there is a paucity of research on whether [such] educational practitioners…are also courtesy-stigmatised’ (2016: 58). Her own study found that indeed, teachers who work with children with behavioural difficulties are considered less intelligent than ‘proper teachers’ (ibid.). Courtesy stigma has been shown to be brought about by the specific association and not through any personal characteristic (Gray, 1993), but this would not be the case with those menstrual researchers who have personal experience of menstruation. Rather, they share the embodied experience they are studying, which complicates analysis of their identification of menstrual stigma in their research, perhaps rendering them both particularly awake to and vulnerable to the occurrence and impact of stigma.

Stigma theory and menstrual research

Erving Goffman (1963) identified stigma as a stain or mark that sets people apart as spoiled or defective. Goffman found that stigmatised individuals suffered profound psychological, social and material consequences. Bourdieu conceptualised the imposition of stigma as a form of symbolic violence with a negative impact on economic, social, cultural and symbolic capitals (1979, 1984, 1987, 1989). Beverley Skeggs (1997) developed Bourdieu’s conceptualisation of capitals in the context of gender and class to show how working-class women’s lack of these various kinds of capital induces a tenuous sense of self-worth. Skeggs’s empirical research on female care workers in the North of England found that respectability was employed as a compensation for low capitals, for example, through emphasising cleanliness and attention to hygiene as attributes of good character (1997). Skeggs found that caring for others is a source of accessible cultural capital for working-class women, while caring for self is denied: ‘their self is for others’ (1997: 65). These findings are readily applicable to menstrual experience with its normative focus on being ‘sanitary’ and ‘hygienic’; on substituting concealment and stoicism for more genuine self-care; and its low/zero levels of associated capitals (Owen, 2022). To the categories of gender and class, we can add race, gender identity, sexual orientation, age, neurodiversity and (dis)ability to the list of under-capitalised characteristics that can constitute elements in the nexus of menstrual stigmatisation and which can multiply its effects. Silencing, so notable in conventional menstrual protocol, is a manifestation of stigmatisation particularly employed to enforce patriarchal control. Historically, practices such as muzzling and branking (the ‘scold’s bridle’, see Federici, 2004: 101) were used to both mark and silence women (Tyler, 2020). Misogynistic silencing continues today in social media (Beard, 2017) and specifically with regard to comments on menstruation (Sayers and Jones, 2015).

Menstruation is normatively managed through respectability protocols spoken of in euphemisms (‘feminine hygiene’, ‘sanitary products’) that emphasise cleanliness as a corrective to the polluting and abject nature of menstrual blood (e.g. Bobel, 2018). Menstrual stigma in many societies serves as a focal point for androcentric power dynamics and allows for the enactment of that power over women and non-cis menstruators (de Beauvoir, 1953; Laws, 1985, 1990; Owen, 1993). These power dynamics are funnelled through menstrual stigma in the form of admonitions as to what menstruators can and cannot do, where they can and cannot go, and through the requirement to ‘pass’ as a non-menstruator (Vostral, 2008): to pretend menstruation is not happening by keeping quiet and acting ‘normally’ even when in intense pain (Young, 2005; Sang et al., 2021). When bleeding, the menstruator typically experiences a loss of status and associated capitals due to the presence of a stigmatised fluid that conventional mores insist must be hidden at all costs (Chrisler, 2011). Additionally, menstruation is a cyclical event that can disrupt availability for sex and work. Within an androcentric capitalist context these factors instil and reproduce zero to low levels of social and economic capitals, while the historically stigmatised status of menstruation means it has no cultural or symbolic capital. Low/no capital is a clear reason why menstruation has been under-researched.

Academia, just like any other profession, has codes of propriety linked to jobs, funding, and hierarchical structures of respect and approval. Sang et al. (2021) found that menstruation was stigmatised in academic workplaces, just as in other contexts. This raises the question of whether it is possible to be a fully respected academic when pursuing research into such a profoundly stigmatised topic. Rather, Chrisler et al. (2011) surmised that, by association, menstrual researchers suffer adverse consequences in their career progression. As this article will show, academics pursuing menstrual research have been encouraged to switch topics for their careers to progress, and many still feel the need to do so. Not being able to get funding and permanent positions based on menstrual research indicates that there are financial penalties for pursuing such research. Academia is an intellectual profession operating in most countries—and certainly in the Global North—within a capitalist, for-profit and product-focused society. Research costs money. From around 2010 onwards, menstruation began to accrue capitals through the disruption of stigma by activist efforts. Prior to this time, menstrual research barely got any funding at all. This shift can be linked to the taboo-disruption embraced by neoliberal capitalism because the dissolution of taboos opens up new markets (Gammon, 2013).

Research context

The research cohort studied was a group of nine scholars (including myself) from humanities and social science disciplines, living and working in the UK, USA and Russia. This group of eight women and one man came together for a two-year project (2020–22) to research the history of menstrual activism, politics, education and culture, in order to better understand the international and local context of the Period Products (Free Provision) (Scotland) Act (2020), which enshrined in law the right of all residents in Scotland to access free menstrual products (McKay, 2021; Bildhauer, 2021; Vostral, 2022). The group members were all born and raised in the Global North, and two-thirds spoke English as their first language (including myself). As such, in global terms group members were broadly privileged, although were not homogenous in terms of other socioeconomic indicators including race, class background, and sexual orientation.

Due to Covid-19 restrictions, the research group’s planned schedule of in-person seminars with field trips to various Scottish archives had to be scrapped. Instead, the project funding was used to pay research assistants to gather archive material, details of which were uploaded onto a website. Meetings now took place over video calls, with the unintended consequence that the group was able to meet far more often than originally planned. While Covid restrictions scuppered travel and in-person meetings, they supplied a shared experience that united the group, regardless of distance and place of residence.

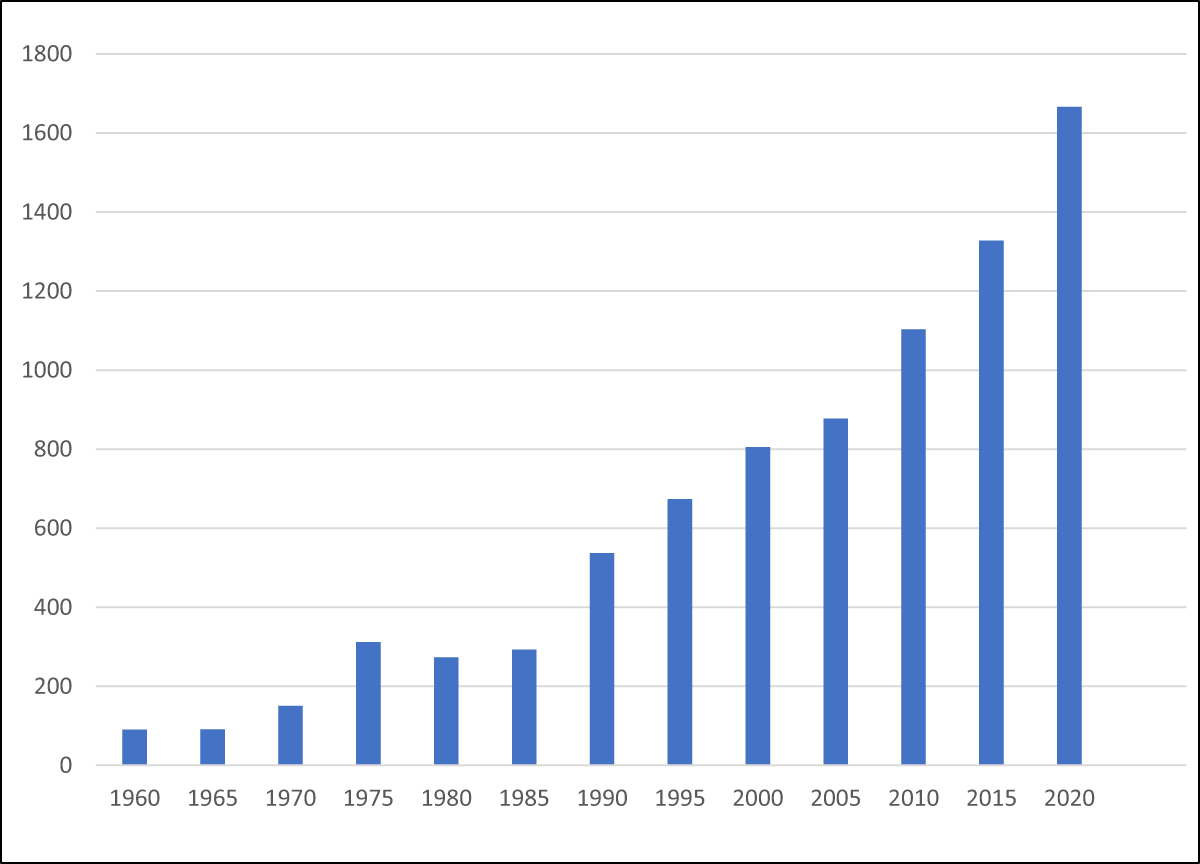

As noted above, the group’s research took place following a decade of change in the social, cultural and political capitals of menstruation. This is shown, for example, through the aforementioned legislation, enacted by a unanimous decision by Scottish parliamentarians to highlight menstrual care as a social justice issue and ‘end period poverty’ (in practice, the concept of ‘period poverty’ has come to chiefly represent the difficulty experienced by those on low incomes in accessing menstrual products). The preceding years had seen funds for menstrual research become more available, with more researchers entering the field, and an accompanying rise in published research (see Figure 1). Correspondingly, it appeared that the cultural capital of the menstrual researcher was perhaps improving in line with broader social changes regarding menstruation.

The information shown in Figure 1 was drawn from a basic search on the word ‘menstrual’ on the University of St Andrews main library database (27 May 2021), using a conventional data-gathering method via keyword for published research (e.g., Critchley et al., 2020). Amounts given are for the specific year indicated, shown in five-yearly intervals. Although the quantity and extent of menstrual research has risen, it remains very low for an experience that affects 51% of the population for approximately 40 years of their lives. In terms of health and wellbeing, menstruation typically involves some degree of suffering (Armour et al., 2019) and is still incompletely understood medically (Critchley et al., 2020) as well as culturally (Bobel et al., 2020). ‘Menstrual’ was chosen as the search term, as it is the word most often used in the titles of humanities and social science papers on menstruation. Adding in papers with ‘menstruation’ in the title augments the 2020 ‘menstrual’ total by 273, making a total of 1,939 for the year. Medical papers usually reference specific syndromes in their titles rather than the broad term of ‘menstruation’. The two most common physical disorders associated with menses are dysmenorrhea and endometriosis: searches for those words in titles add 460 and 4,364 respectively in 2020. There is no directly comparable experience to menstruation in male embodiment. However, it may be worth noting that a search for papers with ‘prostate’ in the title revealed 24,219 peer-reviewed journal articles published in 2020.

Methodology

Autoethnographic enquiry

As mentioned above, I was also a member of the research group I was studying. To incorporate my self-reflexivity, this paper is structured through an autoethnographic enquiry, employing autobiographical vignettes ‘as an alternative approach to representation and reflexivity in qualitative research’ (Humphreys, 2005: 840). I chose to structure the paper this way in order to enrich my data and the storytelling of it (Dyer and Wilkins, 1991), and to be explicit about my own bias and subjectivities: ‘the ethnographer’s own taken-for-granted understandings of the social world under scrutiny’ (Van Maanen 1988, quoted in Humphreys, 2005: 840). I use two ways of inserting vignettes from my own background: (1) moments of epiphany (Ellis et al., 2011: 275) and (2) autobiographical narrative written from a political and social justice perspective (Holman Jones, 2005; Adams and Holman Jones, 2008). These vignettes are graphically distinguished from the rest of the text and preceded by the year in which they took place; commentary upon them is integrated into the text.

Research method

My qualitative, interview-based research concerned both the long-term and more immediate impact of doing menstrual research upon the professional lives of the researchers. The central research question was broad: What has been the subjective experience of menstrual researchers concerning menstrual stigma in their professional lives? Ethical approval for the research was granted by the University of St Andrews prior to commencement (UTREC approval code ML15240). Interviews were conducted in early 2021 on the Zoom online video platform, and were audio recorded and professionally transcribed. Each participant was interviewed once, for 30–60 minutes, with a few participants volunteering follow-up thoughts that occurred to them after the interview. In each interview, I asked three short questions on how long, in how many institutions, and to what extent the interviewee had pursued research on menstruation, followed by three semi-structured, open-ended questions on the perceived impact of menstrual stigma on their academic careers, focusing on their experience of grants, publishing, and career progression.

The data was analysed via first-cycle coding (chiefly descriptive, process, values, and evaluation coding, see Miles et al., 2014: 74–76) for themes developed deductively from the interview questions and inductively from interview comments, and extracted in data ‘chunks’ (ibid.) of quotes, sometimes including a section of conversation between myself and the interviewee. The coded data was then analysed for pattern (or meta) codes through a second cycle, which generated ‘explanatory or inferential codes, obtained by grouping first cycle codes’ into ‘more meaningful and parsimonious units of analysis’ (Miles et al., 2014: 86). In writing up, contributions were anonymised and details de-identified. In the spirit of feminist collaboration and transparency, the paper was shared with the research cohort as part of the workshopping of our collective special issue, and their feedback was incorporated into the paper’s development.

Findings and Discussion

The research participants had developed their interest in menstrual research in different decades and were at different career stages. Three of the researchers had entered the field of menstrual studies in the 1990s, one in 2009, and the remaining five since 2013. Two of the most recent researchers had only been studying in the field since 2019. Out of the whole group, two were professors, two were senior lecturers (associate professor equivalent), two were post-doctoral research fellows, and three were in or just completing PhD programmes. Only one had pursued menstrual research throughout her career, with others dropping in and out depending on funding, research interests, and other factors. The current percentage of their research time devoted to menstruation varied: for three it was 100%, for one, 70%, and for another, 10%. For the remaining four, the figure fell between 50 and 30%. Overall, the mean for the group was 60%.

Here I discuss the research findings through three umbrella themes: (1) mechanisms of historic and continuing barriers to menstrual research; (2) strategies researchers use for managing and navigating menstrual stigma; and (3) the impact of recent changes in public discourse on the field of menstrual studies.

Mechanisms of historic and continuing barriers to menstrual research

Most of the participants, especially those who had been engaged with menstrual research for decades, spoke of difficult encounters with patriarchal gatekeepers, times when doors closed despite the quality of their work. I identified three main mechanisms that reproduced menstrual stigma and enacted barriers to pursuing careers in menstrual studies: (a) ridicule/diminution; (b) silencing/disregard; and (c) persistent ignorance.

Ridicule and diminution

1993. My book on cultural attitudes to menstruation and how they repress women’s agency and power has just been published by a (different) major US publisher. I am assigned an inexperienced publicist who works hard to get radio spots. I am expecting a reasonably intelligent discussion, or at least curiosity. Instead, male broadcasters position both me and the topic as a joke. After three of these excruciating ‘interviews’, I decline to do any more. During this time, I repeatedly dream of a cold, angry group of men, a father and his adult sons, who want to kill me. I feel under siege from the patriarchy.

I realised that menstruation was for a long time too embarrassing to be taken seriously and too threatening not to be immediately disarmed by ridicule. The same applies in academia in various topics to do with female embodiment which are disarmed to similar effect, often by diminishment rather than humour. One participant told me: ‘When I finished my PhD my supervisor was trying to get a research grant [for a history of sexuality] and asked if I wanted to be the named researcher on it. So I said, “Yes, of course, I’d love a job, thank you.” And when he got the money he said, “Well we need to divide up this thing by theme, would you like to do the girlie topics of contraception and abortion?”’

The trivialising of female reproductive lived experience is routinely deployed as a way to deflect the reality that reproduction in all its manifestations and phases is a physically and emotionally complex and even dangerous part of life. When challenged, joking around is often positioned as a kindness and not something that was intended to harm. Yet such trivialisation does do harm: it upholds patriarchal structures by diminishing female agency and vitality, and therefore the possibility of fully owning female embodiment and experience.

Silencing/the brick wall

2000: For the past four years I’ve been searching for a PhD supervisor. I’m losing heart, but today I’m on my way to meet with an upcoming luminary of feminist scholarship, thanks to the intervention of a mutual friend. I should be excited, but I feel out of sorts, perhaps because I dread yet another disappointment. I get lost and arrive late, hot and anxious. The meeting quickly unravels into a complete disaster. I manage a couple of sentences on what I want to research before she says coldly, ‘I can’t help you, I have no interest in menstruation as a topic.’ I feel hopeless and exhausted, and decide I will have to let go of the idea of a PhD.

Several participants had had experience of their menstrual research being stopped, of meeting a brick wall of uninterest. Academic careers are rarely straightforward these days, but the absence of any kind of a clear way forward in developing a career in menstrual research was notable in the stories of these researchers. In 2000, after completing her PhD, one participant told me, ‘I couldn’t get a postdoc [research fellowship] in the area [of menstrual history] that I was proposing, so I had to move away from menstrual scholarship.’ In 2021, after completing a post-doc on menstrual history, another said: ‘I’m still applying for jobs that would allow me to do that [move back to menstrual research full-time]. I still check the job market every day.’ So the brick wall may have moved from doing the PhD, to the end of the PhD, to the end of the post-doc, but it is still very much in place. I asked one participant, ‘Can you see it, in your lifetime, being a Professor of Critical Menstrual Studies or whatever? Can you imagine that? Because you’d be well placed for it.’ The reply was salutary. ‘No, I can’t imagine that.’

Ignorance

2015: I’ve just completed a two-year research project for a feminist organization, on the lived experience of menstruation and menopause in over 3,000 women and girls. It’s been good but I’ve felt frustrated in various ways, and I know I need to up my game to not feel like this for the rest of my career. The old idea that I really should do a PhD returns. I apply to a History department where there is a supervisor who wants to work with me, but the institutional guardians think I’ve been out of academia for too long (at least, that’s what they say). I apply to a large Women and Gender Studies department at another major school, and am told, ‘We don’t have anyone here who *could* supervise a PhD on menstruation.’

Silencing leads to a lack of breadth and depth of scholarship. The lack of scholarship concretises ignorance, obstructing publishing (few peer reviewers), hiring (lack of understanding of the topic), and grant funding and promotion (disregard for the topic’s relevance and applicability). One participant told me:

Most peer reviewers will have lots of insight on theory but they just don’t know what menstruation is. I’m constantly asked to add in things like ‘What is menstruation?’; ‘What is period poverty?’ Which has nothing to do with what I’ve researched. But you still need to do that.

Another discussed how ignorance impacts upon feedback and developing the field:

I did my PhD also on a relatively unusual subject, and there were also few questions because I think people didn’t feel confident enough. The questions [that were asked] were not very academic or intellectually stimulating. It was very much my experience that people see a certain intellectual and academic quality and that is why they are willing to hire you or to grant you a doctoral degree, but they are not really ready to engage with this [topic] substantially. It might lead to this marginalisation again because usually there will be one person [in the department] who does this strange thing and all the others are doing something much more conventional.

A long-term researcher described how ignorance impacted upon the isolation of early menstrual researchers:

I think there were just so many reactions that I finally figured out, okay I have to be very deliberate. What am I trying to do? What point am I trying to make? What am I trying to say? I remember being at a party, mostly English Professors, and they kept saying, ‘But what theories are you using? What’s your theory?’ And I’m like, ‘I don’t have a theory yet.’ It wasn’t like there were whole bodies of stuff to fall upon. I was creating my own archive, my own timeline and it was like, ‘Gosh I’ve got to do all this just to put it together before I can decide what theories am I using.’ That was my 20-ish year-old self too.

Shallowness in the field reflects and reproduces gendered ignorance of women’s issues.

2017: In the first public review of my proposed PhD thesis on menstrual organization, a fellow student (male) asked, ‘But why is this something that even needs to be studied at all?’

The historic concealment of menstruation means that men tend to be particularly ignorant of its impact upon lived experience, and the bias they consequently have against taking it seriously may be unconsciously held. We know that unconscious bias affects women’s careers directly in academic contexts (e.g. Teelken, Taminiau and Rosenmöller, 2021), but we know less about the ways in which it impacts the study of stigmatised topics that concern women, such as menstruation. Academic posts and research projects are increasingly funded through highly competitive grants, and funders’ ignorance on menstruation as a meaningful area of study is compounded by the continuing dominance of men at high ranks who make the funding decisions. The gender imbalance in many departments at top levels maintains a status quo that reproduces androcentric research through unconscious bias and ignorance of topics. The masculinised system begets itself.

Verhoeven (2017) found that researchers are more likely to be awarded a research grant if their name is Dave than if they are a woman of any name, and are also highly likely to work in all-male teams. In menstrual studies, not only are there very few academics working at the rank of professor, (which rank is often demanded by major funders to lead large projects and submit bids), no one studying menstruation at that rank is male. And in an era in which casualisation and fixed terms have come to dominate hiring practices, the number of permanent appointments has dropped, impacting the ability for up-and-coming researchers to apply. As one participant noted:

It is so stupid that it has to be a permanent person who applies for big grants, which is why, I think, we’ve [only] had success in small grants. Because us fixed-term people, you know, that’s what we can apply for, you know? I cannot apply for a big grant.

The same researcher also commented, ‘I’ve been quite successful in securing research funding. [But] it seems like we’re hitting a level…..when you get up to the serious or the big or the prestigious grants, I and others have not been successful yet.’ When grants cannot be obtained then research is starved of support, and consequently new knowledge is not generated, maintaining ignorance of the topic.

Managing and navigating menstrual stigma

Most researchers referenced ways in which they managed menstrual stigma and navigated its effects. These were chiefly: (1) working harder to compensate; (2) dissembling about their topic in public settings; (3) adapting their career path; (4) managing through complaint, while refusing to be a victim.

Compensation

Silencing constrains the field, and such constraint impacts the quality and legitimacy of the work, with knock-on effects. One participant, a long-term scholar in menstrual research, spoke about the additional pressure that stigma adds to academic work.

Yes, I’ve tried to be so careful and so accurate, and I still make mistakes obviously, but [I feel like] I have to have even more evidence or it has to be even better grounded in literature just so people can’t take you down on that, because the whole topic is a question mark to some people. I always felt like I had to be very careful.

Stigma coexists with suspicion and distrust, and menstrual stigma has perseverated in academia even through the past decade of positive change. A participant who had just completed a three-year post-doctoral research project on menstrual cultural history and published several papers on the topic nonetheless felt the backwash of stigma continuing to impact on her work and what was expected of her. Despite being highly qualified, she could not find a research post to continue her work and had recently had to switch topics to something more mainstream.

You have to work so hard to make this [menstrual research] seem like proper academic work. And we’re not alone in that. I think we share something with people who work on other stigmatised topics in that you really have to sell it and use the right terms and the right disciplines and make it academic in a way that I think people in more traditional fields of scholarship don’t have to do.

Similarly, it was noted that grant applications, while daunting under present circumstances, might be navigable through strategy. One researcher commented:

I remain hopeful. I think it’s about hacking the application system and making [the application] even more formal, even more academic, even more dry. And we have to divorce ourselves from the activist tone. The activist tone can get you small grants but it will not get you big grants is what I’m starting to learn. But this is still an ongoing process.

Dissembling

For many years I thought people like the man who turned white, or the woman who was terrified to publish a book, were frozen and uneducated in their reactions. Later I came to a kinder understanding of the mental and emotional blocks thrown up by stigmatisation. When we are taught stigma, we are simultaneously taught aversion: to turn our head, not look, and not be seen to engage.

When I began to talk about menstruation in mainstream and public settings, I did not have any of the dissembling tricks I later developed to protect the enquirer/audience and myself. Over time, when asked about my work socially in unfamiliar settings, I learnt to say ‘women’s health’ first and to get into details later if asked for more specific information. Depending on the context, I learned to say ‘the menstrual cycle’ or ‘periods’ rather than menstruation. These strictures went against the grain, but I felt a need to respect where people were, and to bring them with me gradually rather than shutting them down with a shock.

In academia such attitudes and strategies may also appear to be necessary and dealing with reactions can be experienced as an emotional burden on the researcher. One long-term researcher said, ‘Normally when somebody asks me about my research I say, history or whatever, and that’s all fine, but if I say menstruation you always have to be prepared for an emotional rejection or reaction of some form, right? There is more baggage, definitely, than in other research areas that I do.’

Adaptation

In 2014, I spoke with two successful Australian academics who in the 1990s had each written an excellent, ground-breaking, qualitative social studies PhD thesis on menstruation. Both referred to the topic as a ‘career killer’ and told me they had quickly switched specialisms after graduation.

By 2021, such considerations were still in play. All the researchers in my study who had entered the field in the last decade expressed concerns about how their careers would play out if they focused entirely on menstrual studies. For some, this did not matter too much because they either knew they wanted to, or thought they would most likely want to, study other topics. ‘I think it is possible that in ten or fifteen years I will be doing something else which might not be connected to the menstrual cycle in any way. I think it is a research project rather than a definition of who I am academically.’

For others, the problem of menstrual stigma became a key factor guiding their career strategy. One researcher said:

I never had anyone say, ‘ooh, that’s gross’ or ‘why are you doing that?’ or ‘don’t do that.’ It’s been a bit more subtle. I’ve seen very distinct gender dynamics of men doing a longer double take perhaps than women do when I tell my topic. I had professors when I was working on my Master’s thesis [on menstruation], both of them, just caution me, never saying I shouldn’t do it, but just putting that idea of, ‘How do you want to present yourself as a scholar?’ And they commented about [how] people can get pigeonholed into one thing and it’s very hard to break away from that.

As a result of these comments:

I was very conscious of how I would market myself as a scholar, what opportunities would be there for me after I completed my degrees. I realised trying to get a job solely as a menstrual scholar would be very difficult. That was something I was very conscious of. So I was never going to be a menstrual scholar, I was going to be a scholar of [an established discipline] and part of what I would do is menstruation. I was looking ahead and really trying to make a calculated move as to how I would position myself so that I could still do menstrual research without being side-lined or pushed into a corner or stereotyped as that one scholar doing that.

A PhD student thinking about their future said:

From the experiences of others and hearing about going through [major grant applications] and thinking about the discussions that I have with my cohort about research and what people want to do in the future, it’s something that worries me a little bit—that if I continue to go down the route of reproductive health or menstruation specifically that it is a real struggle.

However, they did not want to change the emphasis of their research: ‘It’s something that I would still want to do regardless, I think.’

Workarounds also have had to be found in publishing. The topic of menstruation is by its nature interdisciplinary; influencing and being influenced by many areas of study in the humanities and social sciences, as well as medicine and biology. While interdisciplinarity has become popular in recent years with some significant funders, other areas of academia have yet to adjust to the concept, including journals, university presses, and departments, which have been historically structured into discrete disciplines. Several of the experienced, much-published researchers commented on this problem. ‘I think [difficulty getting published on the topic] is in part to do with the fact that it’s so interdisciplinary, that it’s hard to slot into a particular niche or series.’ Another said, ‘The resistance by some publishers to be[ing] more interdisciplinary was for me hugely disappointing.’ Menstrual researchers have responded to challenges surrounding publication in various ways, for example by making new knowledge as widely available as possible by publishing in open access fora, (e.g. Bobel et al.’s Critical Menstruation Studies, 2020, and this special collection).

Complaint

Feminist research inevitably carries with it the taint of complaint, and indeed, feminist activism and women’s lives are frequently managed through complaint (Ahmed, 2021). A colleague asked me if I would include my personal experiences of menstrual research in this paper, which I was already, somewhat reluctantly, thinking I might need to do. I realised I was resisting an autoethnographic approach because I hate to be seen to complain, and to be potentially perceived as positioning myself as a victim. I am aware that I chose this topic; it was not inflicted upon me. Researching a stigmatised topic does not necessarily mean one primarily identifies with victimisation. Rather it can mean one does not, and the very notion can sit uncomfortably with the desire to find out more about a poorly understood area.

Stoicism, the alternative strategy to complaint, is a learned survival trait in demanding professional careers, and academia is no exception. One participant told me:

I don’t know, with our funding disappointments, to what extent that has to do with the topic. You know, I always like to think not, ‘It can’t be, they’re just judged on intellectual merit,’ and you never get enough feedback to really be able to fully grasp it. I did have the impression on one of the feedback forms that we got that some of it was antifeminist, that our approach was too decidedly political for that particular funder, but usually it’s hard to see why the applications are rejected. But then that’s also me, you know, like I don’t like to be the victim of any prejudice (laughs), so I like to put a positive spin on it.

Yet, unless menstrual researchers can circumvent any personal distaste for complaint and clearly identify ways in which their work and topic are adversely affected by prejudice, they will be less equipped to confront the means through which stigma is stealthily reproduced via, for example, minimisation and invalidation.

Impact of the changing public discourse surrounding menstruation

Changes in public discourse on menstruation over the past decade were enabled by three main factors (Owen, 2020): the counterpolitics that arose as a reaction to the inequities exposed by the Global Financial Crisis of 2008–2010; the ubiquity and normalisation of social media arising at the same time; and the influence of new technologies in ‘femcare’, chiefly new reusable menstrual products and cycle tracking apps. In this section, I explore this upswing in interest, permission and articulation surrounding menstruation through (1) the impact of changes in menstrual discourse upon the research participants, and (2) the ways in which they experienced this particular research project, which focused on the legislative fruit of the past decade of political change.

The impact of changing menstrual discourse upon researchers

2016: In my renewed quest to do a PhD on menstruation, the rejections of the past year have been horribly familiar. But this time I keep going and then the tide turns. A freakish number of synchronicities come together, and I am enrolled in a PhD with excellent supervisors at a high-ranking university. I have broad departmental support from academics with awareness of gender dynamics in society who are interested in menstruation being a ‘trending topic’. I am awarded a full scholarship.

There was a clear experiential divide between the scholars who embarked on menstrual research before and after the watershed period of 2010–2012, when public discourse surrounding menstruation began to change, accelerating in 2015–16 with the advent of campaigns on ‘period poverty’ (McKay, 2021) and the ‘tampon tax’ (Weiss-Wolf, 2017). Those who came to the field later were often drawn to it because of the change in public discourse. A post-doc researcher said:

I was probably one of many scholars who started paying attention to the popular discourse around menstruation changing, you know, like five years ago [2016]. And then becoming curious about my own taboos against it and then I wanted to learn more. And finding that there wasn’t that much [work on the topic].

The younger cohort of researchers told refreshingly different stories about the reactions of others to their work.

People have been very open, welcoming. I’ve never had a moment of people saying, ‘Oh, that’s disgusting’ or, ‘That’s not a proper topic for research.’ And I think that’s because I’m one of these people who started working on it during and after this current boom, so, I’ve benefited from the change in perception.

As more scholars began investigating the field, increasing numbers of students were drawn to the topic and found themselves absorbed in it. One researcher stumbled into menstrual research as an undergraduate:

In 2013, my second year undergrad, I wrote an essay on how interpretations of menstruation have changed across the modern period. I was completely new to the topic then, and I was kind of like, ‘Wow, we can write histories about this. I like this a lot.’ Because you just go through school being taught World War I, World War II, civil rights, you don’t really delve into social history in more depth.

For graduate students looking for a topic, exposure to scholars taking menstruation seriously could be revelatory.

I just never really thought of it [menstruation] as a viable topic but in 2019 a postdoc and a faculty member in my department gave a talk on their research [on menstrual practices] in Nepal. That was really the first time I had seen a serious research talk around menstruation and menstrual practices. So that just opened the door and planted the seed of, okay this is interesting but not related to what I’m doing [in reproductive health]. But then I started to give myself permission to do a small project around menstruation and that just grew.

Despite the changing discourse, there was common agreement that stigma persists, and that menstrual researchers may have to work extra hard to be respected and supported by their institutions.

The experience of collaborative interdisciplinary menstrual research

While there was sometimes an air of disappointment and even resignation in the interviews, there was also optimism and enthusiasm. In particular there were plenty of spontaneous comments indicating that this particular research project, with its emphasis on collaboration, (common in the sciences but much less so in the social sciences and humanities), had been a revelatory experience for menstrual researchers who had often felt isolated. One of the long-standing academics said:

Having found a community of likeminded researchers is a completely new experience for me. You know, normally I form my communities by going to conferences and they’re very temporary. They’re very stimulating but having a group of researchers actually working together sustainably over a long period, as we do with this project, is completely new for me. It wouldn’t have happened this way if it hadn’t been for Covid, but it is really a model that I love and I would like to keep going in some way.

Another experienced academic commented:

I think it was really well designed to initially start around the Scottish Parliament debates and the bill, to really focus our attention but to approach it from quite different perspectives. Also, it is a really pleasant group in terms of the camaraderie, and I don’t know how much that’s about the topic, but I do think that is part of it. It’s not just that we happen to all be people with interpersonal skills who are able to get along, I think there’s something about the topic to want us to make this work because we feel personally motivated. It’s [menstrual studies] been side-lined for too long and this is the time to really bring it out and subject it to academic scrutiny.

As mentioned earlier, one of the hallmarks of menstrual studies and of this project is interdisciplinarity. Whatever the scholar’s home discipline, it is almost impossible to research and analyse the politics and sociocultural dimensions of menstruation without engaging with multiple disciplines, including history, medicine, public health, sociology, psychology, anthropology, technology studies, business studies, cultural studies, and women’s and gender studies. The interdisciplinarity of the project drew praise and acknowledgment from several participants. ‘I really think the richness of it [the project] has come from our plurality of perspectives.’ The shared knowledge base was also acknowledged as revelatory.

I think it’s the first time I’ve had so many meetings with people who don’t ask what is menstruation, you know? Like, they know the basic facts and that’s remarkable. Because we’re from quite different disciplines and backgrounds and age groups. Yet we can talk to each other. And it’s nice to have a group of peers. So, that has been important. And maybe, you know, there’s good fruitful soil there for other things to grow.

This researcher had recently experienced a significant career setback for their menstrual research, which they acknowledged affected their responses in the interview. They expressed some concerns going forward:

It strikes me how dominated we are by early career and, you know, even PhD students. It worries me because almost all of us will have to go through job applications very, very, soon. And, you know, that could lead to good things, [but] it could also mean that we lose some of the momentum. But whatever happens, we’ve established a group of people we can talk to, send our articles to, in an honest way. And I think that’s valuable, you know? And also, people we can disagree with, productively. It’s just more exciting to have people who get it. So, that’s my feeling. Personally, I’ve felt it has been really good. But I’m just concerned that we [might] create this illusion for the younger people, thinking this is what it’s like, because it’s not, this is the exception. Hopefully we can keep it going.

One of the experienced researchers was careful to position the project in a long-term growth context, and from a positive perspective: ‘We are building a shared knowledge base and shared interests and I think people [inside and outside the group] are seeing that this topic has legs and that you can do something intelligent with it and that it’s important.’

Conclusion

This paper has looked at the impact of menstrual stigma on the researcher. Despite significant social change in perspectives on menstruation over the past decade, academic progress continues to be limited. The menstrual researchers in my case study experienced challenges they considered to be stigma-related in publishing menstrual research, obtaining permanent positions centred on their specialisation, and attracting long-term and large-scale funding. Yet this stigma, this apparent barrier to funding, publishing and career progression, is a large part of what makes menstruation important and interesting as a topic for research. The researchers were united in finding menstruation to be a topic of particularly strong interest in which there was still much important work to be done. At the same time, they understood there was inevitable emotional labour involved in navigating such complex professional terrain, and seemed to accept, if not willingly, that they would face probable setbacks despite the quality of their work and the importance of the topic. There was particular angst in two strongly interlinked areas: the path to promotion, and success in getting grant funding. While participants had been successful in obtaining small grants (mostly for individuals), so far, despite much hard work on applications, no significant large and long-term grants had been awarded to teams of menstrual scholars to their knowledge.

This research shows the impact of multiple effects of stigma upon the careers of menstrual researchers and demonstrates the relationship between stigma and capitals. For academics, being able to publish research, obtain permanent positions and attract major funding are the main avenues through which they accumulate social, economic and cultural capitals, and in so doing protect themselves from the symbolic violence and literal poverty of precarity. My findings elucidate some of the mechanisms through which longstanding symbolic domination surrounding menstruation is ‘everywhere and nowhere’ and thus very hard to counteract (Bourdieu quoted in Bourdieu and Eagleton, 1992).

Indeed, this research on a small cohort of scholars shows how entrenched stigma can lead to a feedback loop from which it is difficult to escape, and suggests that academics working on stigmatised topics may need specific types of institutional support in order to progress, publish and flourish. Acknowledgement of stigma would be a first step in alerting committees to unconscious bias. Acknowledgement of the brick wall in jobs—which several participants noted has moved in recent years from pre-PhD to post-doc to post post-doc—and funding is important to highlight at the institutional level, as highly capable academics may be being side-lined as a result. There is still no Professor of Critical Menstrual Studies.

Acknowledgements

Many thanks to my colleagues for their generous participation in this case study, and to the Royal Society of Edinburgh for funding support for our joint project.

Competing Interests

The author’s role as a coordinator of the larger research project for this special collection has not led to a conflict of interests. Research interviews and interactions concerning the research in this article were boundaried from any administrative matters or collegial meetings.

References

Adams, T E and Holman Jones, S 2008 Autoethnography is queer. In: Denzin, N.K., Lincoln, Y.S. & Smith, L.T. (eds), Handbook of critical and indigenous methodologies. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. pp. 373–390. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4135/9781483385686.n18

Ahmed, S 2021 Complaint! Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Armour, M, Parry, K, Manohar, N, Holmes, K, Ferfolja, T, Curry, C, Macmillan, F and Smith, C A 2019 The prevalence and academic impact of dysmenorrhea in 21,573 young women: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Journal of Women’s Health, 28(8), 1161–1171. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1089/jwh.2018.7615

Beard, M 2017 Women & power: A manifesto. London: Profile.

Bildhauer, B 2021 Uniting the nation through transcending menstrual blood: The Period Products Act in historical perspective. In: Bildhauer, B, Røstvik, C M & Vostral, S (eds.), Open Library of Humanities 8(1). DOI: http://doi.org/10.16995/olh.6339

Bobel, C 2018 The managed body: Developing girls and menstrual health in the Global South. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-89414-0

Bobel, C, Winkler, I, Fahs, B, Hasson, K A, Kissling, E A and Roberts, T A (eds.) 2020 The Palgrave handbook of Critical Menstruation Studies. New York: Palgrave MacMillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-981-15-0614-7

Bourdieu, P 1979 Symbolic power. Critique of Anthropology, 4: 77–85. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0308275X7900401307

Bourdieu, P 1984 Distinction: A social critique of the judgement of taste. London: Routledge.

Bourdieu, P 1987 What makes a social class? On the theoretical and practical existence of groups. Berkeley Journal of Sociology, 32: 1–17.

Bourdieu, P 1989 Social space and symbolic power. Sociological Theory, 7: 14–25. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/202060

Bourdieu, P and Eagleton, T 1992 In conversation: Doxa and Common Life. New Left Review, 191: 111–121.

Broomhead, K E 2016 ‘They think that if you’re a teacher here … you’re not clever enough to be a proper teacher’: The courtesy stigma experienced by teachers employed at schools for pupils with behavioural, emotional and social difficulties (BESD). Journal of Research in Special Educational Needs 16(1): 57–64. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1471-3802.12056

Buckley, T and Gottlieb, A (eds.) 1988 Blood magic: The Anthropology of menstruation. Berkeley: University of California Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1525/9780520340565

Chrisler, J C 2011 Leaks, lumps, and lines: Stigma and women’s bodies. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 35: 202–214. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0361684310397698

Chrisler, J C 2013 Teaching taboo topics: Menstruation, menopause, and the psychology of women. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 37(1): 128–132. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0361684312471326

Chrisler, J C, Johnston-Robledo, I & Gorman, J A 2011 Stigma by association? The career progression of menstrual cycle researchers. Paper presented at the meeting of the Society for Menstrual Cycle Research, Pittsburgh, PA on June 24 2011.

Critchley, H et al. 2020 Menstruation: science and society. American Journal of Obstetrics & Gynecology. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2020.06.004

De Beauvoir, S 1949/1953 The second sex. New York: Vintage, 2011.

Douglas, M 1966/2002 Purity and danger: An analysis of concepts of pollution and taboo. London: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Dyer, W G and Wilkins, A L 1991 Better stories not better constructs, to generate better theory: A rejoinder to Eisenhardt. Academy of Management Review, 16(3): 613–619. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5465/amr.1991.4279492

Ellis, C, Adams, T E and Bochner, A P 2011 Autoethnography: An overview. Historical Social Research, 36(4): 273–290.

Federici, S 2004 Caliban and the witch: Women, the body and primitive accumulation. New York: Autonomedia.

Gammon, E 2013 The psycho- and sociogenesis of neoliberalism. Critical Sociology, 39(4): 511–528. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/0896920512444634

Goffman, E 1963 Stigma: Notes on the management of spoiled identity. Englewood Cliffs: Prentice-Hall.

Gray, D E 1993 Perceptions of stigma: the parents of autistic children. Sociology of Health & Illness, 15(1): 102–20. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/1467-9566.ep11343802

Hinshaw, S P 2005 The stigmatization of mental illness in children and parents: Developmental issues, family concerns, and research needs. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 46(7), 714–34. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/j.1469-7610.2005.01456.x

Holman Jones, S 2005. Autoethnography: Making the personal political. In: Denzin, N.K. & Lincoln, Y.S. (eds), Handbook of qualitative research. Thousand Oaks, California: SAGE Publications. pp. 763–791.

Humphreys, M 2005 Getting personal: Reflexivity and autoethnographic vignettes. Qualitative Inquiry, 11(6): 840–860. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1177/1077800404269425

Johnston-Robledo, I and Chrisler, J 2013 The menstrual mark: Menstruation as social stigma. Sex Roles, 68(1–2): 9–18. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/s11199-011-0052-z

Laws, S 1985 Male power and the menstrual etiquette. In: Homans, H. (ed.), The sexual politics of reproduction. Gower, Aldershot, Hants: Ashgate Publishing. pp. 13–29.

Laws, S 1990 Issues of blood: The politics of menstruation. London: Macmillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-349-21176-0

McKay, F 2021 Scotland and Period Poverty: A case study of media and political agenda setting. In: Morrison, J, Birks, J, and Berry, M (eds), Routledge companion to political journalism. London: Routledge. [Forthcoming]. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9780429284571-38

Miles, M B, Huberman, A M and Saldaña, J 2014 Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE Publications.

Owen, L 1993, 2008 Her blood is gold. Blandford, Dorset: Archive Publishing.

Owen, L 2018 Menstruation and humanistic management at work: The development and implementation of a menstrual workplace policy. Journal of the Association for Management Education & Development, 25(4): 23–31.

Owen, L 2020 PhD thesis, Monash University. Innovations in menstrual organisation: Redistributing boundaries, capitals, and labour. DOI: http://doi.org/10.26180/5ed437df63c80

Owen, L 2022 Stigma, sustainability and capitals: A case study on the menstrual cup. Gender, Work and Organization.

Page, R M 1985 Stigma. London: Routledge.

Pascoe, C 2007 Silence and the history of menstruation. Oral History Association of Australia, 29: 28–33.

Sang, K, Remnant, J, Calvard, T and Myhill, K 2021 Blood work: Managing menstruation, menopause and gynaecological health in the workplace. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(4): 1951. DOI: http://doi.org/10.3390/ijerph18041951

Sayers, J G and Jones, D 2015 Truth scribbled in blood: Women’s work, menstruation and poetry. Gender, Work & Organization, 22(2): 94–111. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1111/gwao.12059

Skeggs, B 1997 Formations of class & gender: Becoming respectable. London: SAGE Publications.

Teelken, C, Taminiau, Y and Rosenmöller, C 2021 Career mobility from associate to full professor in academia: Micro-political practices and implicit gender stereotypes. Studies in Higher Education, 46(4): 836–850. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/03075079.2019.1655725

Tyler, I 2020 Stigma: The machinery of inequality. London: Zed. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5040/9781350222809

Van Maanen, J 1988 Tales of the field: On writing ethnography. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Verhoeven, D 2017 http://debverhoeven.com/australian-research-daversity-problem-analysis-shows-many-men-work-mostly-men/ [Last Accessed 14 Jan 2022]

Vostral, S L 2008 Under wraps: A history of menstrual hygiene technology. Plymouth: Lexington Books.

Vostral, S L 2022 Periods and the Menstrualscape: The politics of menstrual technology adoption in Scotland and the United States, 1870–2020. In Bildhauer, B., Røstvik, C. M. & Vostral, S. (eds), Open Library of Humanities 8(1). [Forthcoming]

Weiss-Wolf, J 2017 Periods gone public: Taking a stand for menstrual equity. New York: Arcade.

Young, I M 2005 Menstrual meditations. In: Young, I. M., On female body experience: “Throwing like a girl” and other essays. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 97–122. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/0195161920.003.0007