In the wake of the 2008 global economic collapse, retroactively termed the Great Recession, both visual artists and critics turned to the genre of documentary to make sense of the social, psychological, and political effects of widespread impoverishment.1 Mainstream news coverage focused on the implosion of the subprime mortgage market and subsequent housing market collapse. But, as Annie McLanahan (2016) has detailed, art galleries across the United States also staged group shows and solo exhibitions with titles such as The Great Depression: Foreclosure USA and Foreclosed: Rehousing the American Dream. At the same time, works like Dale Maharidge’s and Michael S. Williamson’s Someplace Like America (2013) and Phil A. Neel’s Hinterland (2018) combined journalism, ethnography, and documentary photography to capture and conceptualize what Maharidge’s and Williamson’s subtitle refers to as ‘the new Great Depression’.

This callback to the 1930s is more than just window dressing. Many of the aesthetic conventions now associated with the genre of documentary originated with the artists and sponsoring agencies who were tasked with explaining the emotional and economic realities of the Great Depression. If the economic situation of the Great Recession has shaped 21st century histories of the Great Depression (Marsh, 2019), it is equally true that the tropes of Depression-era documentary—what the genre does, what type of artist creates it, what it should look like, where it should be viewed—tend to set the criteria for how contemporary artists conceive of Recession-era documentary. So, for example, the Recession has witnessed a resurgence of the photo text, a mode of documentary equally borne out of federally funded relief programs and the print culture of the 1930s. Beginning in 1935, the Farm Security Administration (FSA), directed by Roy Stryker, and the Federal Writers’ Project, a department of the massive Works Progress Administration (WPA), were responsible for employing tens of thousands of people and for producing hundreds of thousands of photographs. These were published and circulated in the form of over 350 books and pamphlets, such as Margaret Bourke-White and Erskine Caldwell’s You Have Seen Their Faces (1937), Archibald MacLeish’s Land of the Free (1938), James Agee and Walker Evans’s Let Us Now Praise Famous Men (1941), and Richard Wright’s and Edwin Rosskam’s 12 Million Black Voices (1941), as well as in national newspapers and magazines (Stott, 1973; Stange, 1989).

Stryker largely staffed the FSA with working professionals and, as part of Stryker’s team, they continued to follow the professional standards of news photojournalism. Staffers were assigned projects through a central office in Washington, D.C, were allocated travel funds, and were usually required to submit a shooting script and outline of their intended coverage. Partially because of this professional standardization, the massive undertaking developed a recognizable FSA style: high contrast, close-cropped portraits of individuals or small groups, intimate images of threadbare domestic spaces, bitingly ironic juxtapositions of impoverished individuals and popular advertising, and an emphasis on the dignity rather than eccentricity or sentimentalism of rural farmers, sharecroppers, and the unemployed (Fluck, 2010).

Recent collaborations, such as the one between the Library of Congress and the non-profit Facing Change: Documenting America, attempt to replicate the New Deal’s state-sponsorship for documentary. However, the 2008 Great Recession did not produce a federally funded documentary project on the scale of the WPA or the FSA-sponsored photography group. Thus, even as contemporary documentary borrows from the FSA style, the institutional and economic arrangement that produces these contemporary works is quite different than the situation experienced by earlier artists. Even more, as McClanahan (2016: 102) explains, the photographer’s new first-hand experience of economic precarity shifts her relationship to the documented subject:

They [Recession photographs] toggle uncertainly between the photojournalist’s desire to give economic insecurity a local habitation and the anxious awareness that insecurity is more everywhere than ever before; between awareness of the increasingly commonplace fact of debt and the wish to disavow it.

That is, unlike the earlier examples in which the professional identity and stable paycheck of the photographer insulated them from their poor subjects, economic collapse can no longer be documented from a safe distance.2 As McClanahan (2016: 113) puts it, precarity is ‘everywhere, rather than anywhere or elsewhere’.

This essay examines two photo texts that exemplify the institutional, technological, and aesthetic afterlives of the Depression-era photo text in contemporary artistic practice, thus linking two high-water marks of documentary expression in the United States. Matt Black’s American Geography (2014–Present) and Radcliffe ‘Ruddy’ Roye’s When Living is a Protest (2015–Present) both adapt the visual style of New Deal documentary established by photographers such as Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, Margaret Bourke-White, and Gordon Parks—a genre that Jeff Allred (2012) refers to as the ‘modernist photo text’—to articulate the after-effects of the 2008 Great Recession as a representational as well as a political problem. However, their means of publication, as serialized posts on the social media platform Instagram, allows for us to see in a new light the institutional bulwarks that supported Depression documentary. Black’s and Roye’s projects exemplify the explosion of amateur cultural production that Instagram, a platform that depends on the normalization of the smart phone as a mass communication technology, makes possible. At the same time, they offer paired but opposite ways that ‘born digital’ literary and visual art can reimagine modernism’s insistence on media specificity for 21st-century artistic works, especially those keyed to capturing the social life of economic crisis.

Roye’s and Black’s projects and their Depression-era forebearers draw attention to an irony at the heart of the financial and visual systems that they take part in: the overabundance of images about poverty, an economic situation defined most basically by a lack of resources (Jones, 2008). Yet the fact that Roye and Black produced social media photo projects exposes how much has changed in documentary expression since the 1930s. A culture of professionalism surrounded New Deal photography and tended to protect the state-employed cultural workers from identification with their subjects, be it specific impoverished individuals, the general threat of impoverishment, or the broader experience of economic precarity. In contrast, Roye’s and Black’s projects reflect the paired democratization and amateurization of image-making in the 21st century, which produces even more competition for attention and financial resources. In short, they capture the erosion of the documenter/documented divide and, at the same time, the shared impoverishment of the people on both sides of the camera lens.

Along with the institutional and professional setting of the Depression photo text, these photographers also help to explore the media technologies that undergird documentary work, both then and now. In Roye’s and Black’s hands, the possibilities of the social media photo text are on full display, because both also work in traditional print venues and have conceived of other photographic projects explicitly for print or for gallery exhibitions.3 In fact, excerpts from American Geography and When Living is a Protest have both been exhibited in galleries, reproduced in periodicals, and collected into books after their initial presentations on Instagram. Their proximity to print, both in the photographers’ other work and in their post-Instagram afterlives, helps to mark what is unique about their existence as social media photo texts. That is, what becomes most striking is their engagement with the platform’s features and limitations. Free access, geo-tagging, captioning, hashtags, comment threads, the square frame, the infinite scroll, the competition with other user accounts, and the lack of compensation for generating content are all front-end considerations.

In what Simone Murray (2018: 35) refers to as ‘the digital literary sphere’, authors and artists alike must embrace, however reluctantly, the ‘bare necessity’ of the app and platform capitalism more broadly as one penumbra of reader engagement and brand building. In fact, as Seth Perlow (2019) has shown, Instagram has birthed whole genres, including that of ‘Insta-poetry’, which is unquestionably the most popular and widely read poetry circulating in the 2010s, even if it is almost entirely invisible from scholarly consideration. Often, these works support the truism within media studies that the content of any new media is an old media: as Perlow shows, Insta-Poetry largely replicates the look of obsolete, paper-based technologies like the typewriter and manuscript, which retroactively take on the characteristics of authenticity and sincerity in a world awash in digital communication.

However, Black’s and Roye’s works differ both from other social media literary production and from documentary works inspired by the FSA style that McClanahan discusses. They neither betray a nostalgia for print nor portray Instagram as a means to an end. Instead, social media publication provides an end in itself, an ‘extra studio, a place to do more’ (Cole, 2015) than self-promotion, to publicly stockpile works-in-progress, or to stand-in for the assumed intimacy of the codex. Certainly, their projects are not emblematic of the application’s aesthetic as a whole, but foregrounding the ways that their work takes place in Instagram’s world of photographic abundance is key to understanding their attempts to update the documentary photo text so as to represent poverty in the 21st century. There is an implicit connection in these projects between, on the one hand, the ubiquity of their social-media specific photographs and the poverty they seek to represent (financial precarity and images of it are both everywhere, unavoidably perma-present in the 2010s) and, on the other, the seeming immateriality of ‘born digital’ works. Their posts circulate digitally and without compensation, as Instagram’s user-created content rather than as traditional art objects, and therefore participate in the publishing and art markets differently than those print-based genres.

Instagram provides access to an audience that is larger and more diverse than even the most successful photo book or museum exhibit. Black’s account has over 225,000 followers and Roye’s has over 280,000, while the best-attended contemporary art exhibits in the US in 2019 (Dianne Arbus and David Levinthal retrospectives, both staged at the Smithsonian American Art Museum, in Washington, D.C.) saw roughly 6,000 and 4,000 daily visitors (Luke, 2020). Yet Instagram also exacerbates conceptual problems that have long dogged documentary. Most pressingly, it risks reducing the genre’s ethical charge, which Ariella Azoulay (2008) describes as the ‘civil contract’ of photography, to what tech journalism calls ‘the tyranny of the square’, a phrase that refers to Instagram’s recently lifted limitation of the 1:1 aspect ratio but more broadly to the platform’s reduction of life to urban self-documentation. Put differently, Black’s and Roye’s Instagram photo texts trace Instagram’s poetics of everyday life to the modernist photo text, and in doing so they both index and ambivalently critique the notion that life is meaningful only to the extent that it is noticed and, hence, documented. As I will explain in the following two sections, these works bring into the 21st century the ethical and formal problems of the modernist photo text regarding the relationship between the individual work and the publishing field that it enters. In their Instagram projects, Black and Roye reimagine a collaborative print mode as single-authored social media projects. They take the identification between the photographer and subject, rather than between the subject and the audience, as the primary concern and, most importantly for the concerns of this essay, they position their claims to represent the subject of poverty as part of a longer modernist tradition of self-conscious engagement with media-specificity.

While American Geography and When Living is a Protest share much in their considerations of the history of documenting poverty, as well as in their attention to the specificity of social media as a publishing platform, they present two incompatible limit points in the aesthetics and ethics of such work. Black’s account of contemporary poverty is structural and impersonal, refusing to tie the moral charge of his images to the biographies of impoverished individuals. He attempts to capture the class structure itself, and by way of geo-tags on Instagram, the geographic spread of poverty. Conversely, Roye focuses on the embodied and subjective experience of single subjects, relying on lyrical prose passages, extensive hash-tagging, and mentions to catalog and circulate images and stories of impoverished individuals in the US. Because of the iterative and potentially endless (rather than serial and, hence, developmental structure) accrual of posts on the Instagram feed, these singular examples of specific poverty remain isolated, never quite coalescing into a shared identity, such as class. These two modes, the impersonally structural and the interpersonally monadic, draw attention to the competing, even ambivalent, possibilities of social media as a publication method for documentary, and more broadly as a tool for social or political intervention. Finally, in their attention to the media constraints of socially engaged artwork, they specifically bring with them another concern that has dogged documentary, and particularly modernist documentary, since the 1930s: how to account for the unavoidable imbalances between the documented subject, the photographer, and the audience.

How the Other 20% Lives

The FSA style grew out of a specific conceptualization of poverty and government intervention native to the New Deal. Specifically, Franklin Delano Roosevelt predicated governmental intervention on the public’s ability to see poverty as a clear and objective problem with equally clear and objective solutions. Only then, he wagered, would the public support the New Deal. Roosevelt (1941: 4–5) laced this language of sympathetic, governmental vision throughout his Second Inaugural address:

I see a great nation, upon a great continent, blessed with a great wealth of natural resources. … I see tens of millions of its citizens who at this very moment are denied the greater part of what the very lowest standards of today call the necessities of life. I see millions of families trying to live on incomes so meager that the pall of family disaster hangs over them day by day. I see one-third of a nation ill-housed, ill-clad, ill-nourished.

Here, Roosevelt’s anaphora-laced giant ‘I’ sees and sees through the starving masses, and his proposed path out of suffering entails incorporating the down-and-out ‘one-third’ into a fully modern majority, a task that they cannot or will not complete on their own (Allred, 2010: 3). Framed in this way, the photographed individuals and locations appear as passive, if not wholly inanimate objects of study, while the documenters and their audience actively shape history.

Yet as many scholars (Rabinowitz, 1992; Allred, 2010; Jones, 2008; Fluck, 2010) argue, the actual FSA photo texts push against this clear-eyed representation of poverty. Allred, for example, highlights how a subset of Depression-era photo texts that he calls ‘documentary modernism’ often use captions and surrounding prose to explore the gap between the urban, culture-working photographer and the rural photographed subject. James Agee (1941: 13) famously refers to himself and Evans as spies prying into the lives of the sharecroppers they document, lamenting that his subjects are ‘now being looked into by still others, who have picked up their living as casually as if it were a book’. And Walker Evans’s carefully staged, highly crafted depictions of rural subjects expose what Winfried Fluck (2010: 65) calls the ‘authenticity effect’ of documentary. Other recent critics (Michaels, 2015: 120) argue that Walker Evans’s photographs in Famous Men demonstrate ‘a kind of negation of the relation between the photographer and his subject’. Surrounded by a visual culture in which rural poverty is so easy to see from a distance, because of the ten thousand other photographs of rural destitution, Depression-era photo texts demonstrate the opaqueness, or the unknowability, of their photographed subjects. In this way, they exemplify modernist practice insofar as they interrupt the assumption of authenticity in photographic documentation. That is, they insist on the aesthetic and epistemic autonomy of the work, as well as the subject in the work. You, reader, can see these faces in the photographs, but you cannot know their experience simply by looking at them.4

If photographers and writers of the 1930s felt burdened by the overabundance of their era’s visual culture, it is hard to know what they would make of the almost unfathomable glut of images on Instagram. The application launched in October 2010 exclusively for Apple iOS and, by 2012, the same year it was bought by Facebook, it became available for most mobile devices and desktop web browsers. As of early 2021, reports claim (Woollaston, 2021) that the service has over 1 billion unique accounts, with roughly 50 million daily active users and 95 million daily shared photographs. This marks what Sean O’Hagan (2018) calls ‘a seismic shift that has occurred in our relationship with—and use of—the photographic image’. The capacious, endlessly refreshing image world created by Instagram has only become possible because of what Alise Tifentale (2015) refers to as the advent of the ‘networked camera’, in which the formerly ancillary feature of smart phones to capture, view, and share digital photographs takes on a new, primary function, while the one-to-one aural communication of the mobile telephone becomes a vestigial feature.

While some critics focus on Instagram’s complicated relationship with contemporary art photography (Wiley, 2011; O’Hagan, 2018), others attempt to make sense of the visual style native to the application. Lev Manovich (2014: 48), for example, refers to it as a new form of ‘social photography’, a ‘mega-documentary, without a script or director’, which makes it nearly impossible to ‘read’ the style of Instagram photos using the traditional methods of cultural criticism other than to notice the preponderance of squares, grids, and self-portraits. Manovich and his research team (2017), having surveyed 2.3 million of these images from global cities such as Bangkok, Berlin, Tokyo, New York, and Rio de Janeiro, concluded that ‘Instagramism’, as much as it can be summarized as a single thing, is analogous to the genre of the family photo album, documenting both mundane occurrences and milestones in anticipation of a future moment when they will be viewed with nostalgia.

In a number of ways, Matt Black’s American Geography situates itself as both a descendent of the Depression-era photo text and a work wholly native to Instagram. The project is comprised of the photos that he took on five cross-country trips across 48 states and over 100,000 miles. It began locally, as an attempt to document the changes he saw taking place in California’s Central Valley where he grew up and still lives. But he eventually saw the agricultural landscape of the Central Valley as just one of many of what he calls (Simon, 2018) the ‘pockets of America that are left out of the narrative’ of post-Recession recovery. When he set out on his trips, he chose his routes by linking together towns and cities where the poverty rate exceeded 20%, a method he calls ‘critical cartography’ (Grow, 2014a). This conflation of photographic seeing with statistical representation quietly echoes the conceptual model of Jacob Riis’s investigation of urban poverty in How the Other Half Lives (1890) as well as Roosevelt’s attention to the ‘one-third’ of impoverished Americans.

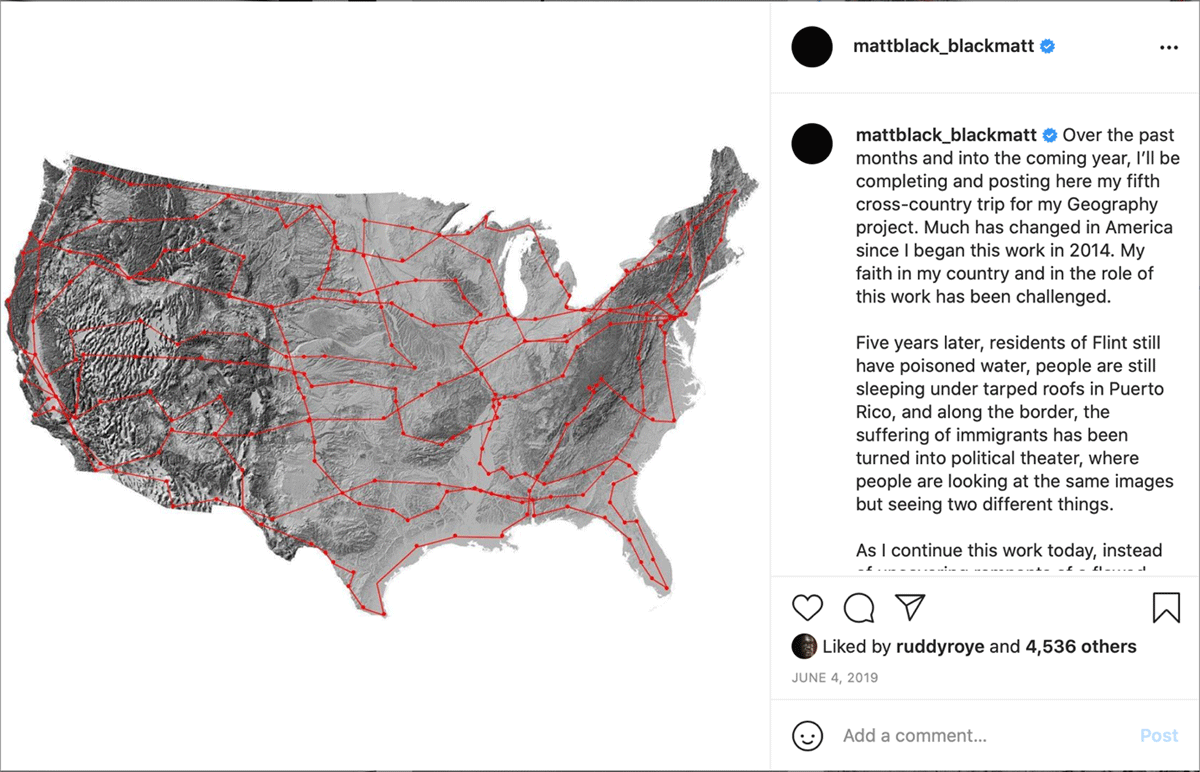

The photographs are spare and use high-contrast black and white, taking clear cues from the FSA documentary works of Walker Evans, Dorothea Lange, and Margaret Bourke-White. In fact, he actively courts these comparisons, such as in the image ‘Sunrise Manor, NV’, which is a straightforward recreation of Walker Evans’ photograph of Floyd Burroughs’s work boots. Yet, for Roosevelt, where the down-and-out ‘one-third’ documented by the FSA exist in an unspecified location outside of the national narrative, Black’s photographs specifically locate these statistics in the landscape. He geo-tags each image that he uploads to the project so that when he finishes each trip he can also post a map of travels (see Figure 1). In an interview (Simon, 2018), he explained, ‘I wanted to find a continuous route that linked all of these towns, which are no more than a couple of hundred miles from each other. And the fact that you can link all of these communities from coast to coast and back again is telling’. The map, for him, is as integral as the photographs and he in fact considers the map’s ability to abstractly represent space to be another feature of the photographic project. ‘Photography and maps are similar’, he says (Laurent, 2014), because ‘they’re born out of the same idea of describing a place for another person to engage with. And, [with Instagram] they are right there, together, on that same platform’. Though for many years the working title of Black’s project was ‘The Geography of Poverty’, he emended it to American Geography in 2020. His maps quite literally outline the US and make economic disparity synonymous with the nation’s geography. It is not important how the other half lives but where they live, which is everywhere.

Map of geo-tagged locations from Matt Black’s cross-country trip. Photo: Matt Black, published on Instagram (4 June 4 2019). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

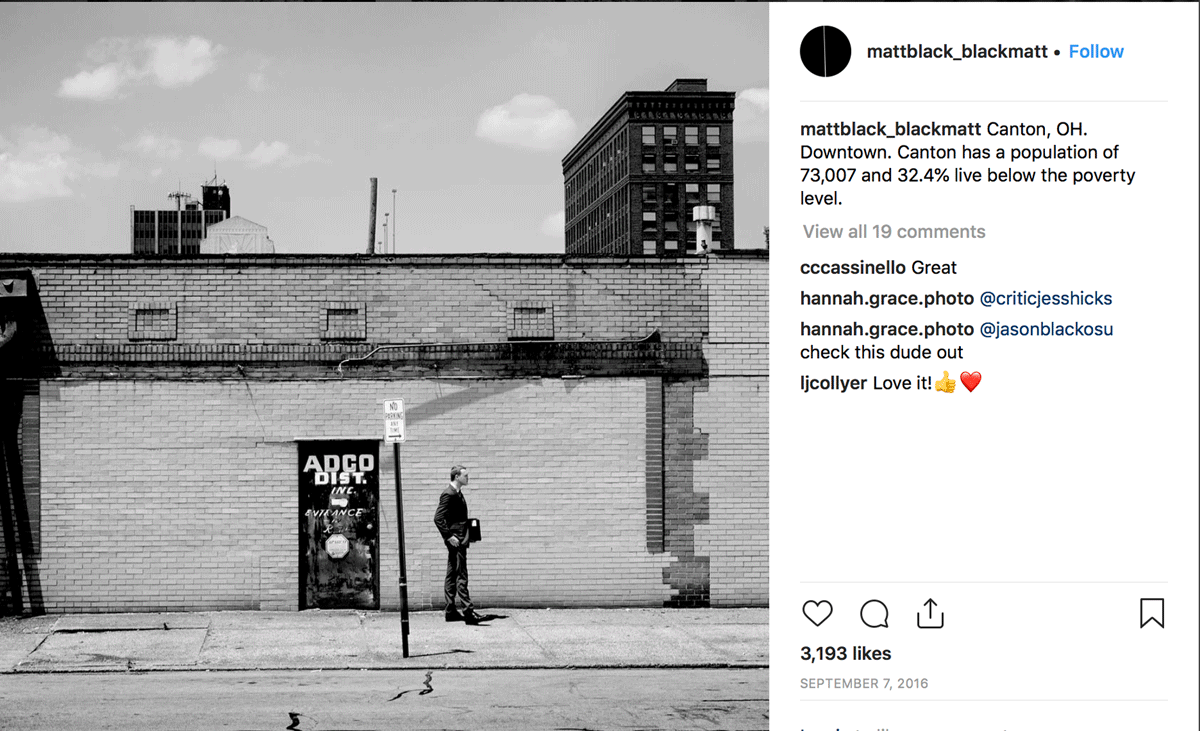

The decisions to visit specific zip codes, use the impersonal tool of census data, and to treat his maps as capstones to each leg of the journey depersonalizes his representations of impoverished people, be they tenant farmers in Alabama, Wal Mart employees in Missouri, or the homeless in New Jersey. This aesthetic of impersonality can be seen in his captions, too, which never provide information on the individual subjects he portrays. The descriptions more closely resemble the dateline than the typical photo-journalistic expository caption: for example, ‘Canton, Ohio. Downtown. Canton has a population of 73,007 and 32.4% live below the poverty level’. Or, even more plainly, ‘Wire. Exeter, California’, followed by the longitude and latitude at which the photo was taken (see Figures 2, 3, 4, 5). American Geography, in this way, is determined to represent the geographical concentration and distribution of poverty, rather than poor people themselves.

Canton, OH. Downtown. Photo: Matt Black, published on Instagram (7 September 2016). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Richmond, VA. Downtown. Photo: Matt Black, published on Instagram (24 July 2015). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Wire. Exeter, CA. Photo: Matt Black, published on Instagram (11 May 2014). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

Salinas, CA. Weeding strawberries. Photo: Matt Black, published on Instagram (12 July, 2016). Reproduced with permission of the artist.

This attention to geography and landscape over individuals also extends into the actual photographs. Unlike Walker Evans’s or Margaret Bourke-White’s photographs of Southern tenant farmers, whose faces are fully lit and who often look directly back into the camera, Black shrouds his subjects in shadows that obscure their facial features, if not their entire bodies. Often, the person at the center of the image appears only as a dark outline in an otherwise bright landscape. For all of the geo-locational tools and maps that depict poverty as a connecting tissue in the U.S., the actual images almost uniformly depict single bodies. They are often shown in full profile against a close, textured wall that reduces the visual depth of the photograph and isolates the subject in the frame. At other times, Black shoots from so far away, or from such a high vantage point, that the landscape becomes a geometric pattern and the depicted individuals appear as white or black dots in the frame. In other photographs, he simply gestures toward the inhabitants of a particular community without depicting them, as in the photograph of a wire against a depthless sky, which in the way it is bent and framed resembles a line drawing of a nose, mouth, and chin. This visual preoccupation with transforming human bodies into abstract geometrical shapes, and in turn seeing human forms in a town’s electrical wires, subtly mirrors the way Instagram organizes and abstracts individual images and user accounts. That is, when a viewer chooses to access Black’s account, the individual photo thumbnails display as a grid of square images which are, in turn, photos of repeating squares, grids, and geometric patterns (see Figure 6). Thus, each photograph in Black’s feed visually doubles its method of circulation, its place in an infinitely scrolling grid of similar images.

These are all aesthetic strategies that play into the visual limitations of photos on Instagram, a platform that users engage with almost exclusively by way of the mobile phone touchscreen. The silhouetted bodies are legible as bodies despite the small, possibly cracked, finger-print marked screens on which they are viewed: they do not demand glossy reproduction in a photo book, high fidelity prints, or proper lighting to be seen. The shallow depth of field and geometric patterns are actually hallmarks of Manovich’s ‘Instagramism’, recognizable everywhere from selfies to pictures of food. Countless ‘how-to’s on Instagram photography explain that a successful image should look flat, that it should maintain a shallow depth of field and present the subject as close to the visual plane of the photograph as possible, that it should emphasize geometric patterns, and it should frame for center and isolate a single key focal point. So Black’s photographs in American Geography show an awareness of the formal limitations and possibilities of Instagram (the size and quality of the image, along with its location among millions of other similar images) and especially how these limitations can be turned into a tool for seeing economic disparity.

One might see Black’s embodied but impersonal photographs as a visual thematization of what Phil A. Neel’s Hinterland (2018) calls the ‘material community of separation’ endemic to the migrant poor. That is, the fact of economic displacement hangs like a web over all locations, while the subjective experience of economic displacement tends towards isolation and felt invisibility rather than community. Black’s refusal to portray his subjects head on, to cover their features with shadows and to flatten the plane of the image, provides a visual corollary to his use of census data. It is a way to make economic precarity impersonal and hence not dependent on the viewer’s sympathetic identification with the photographed individual. The viewer cannot know their faces, and the viewer cannot see their faces either. But, as Black makes clear, those are unrelated to seeing the sociological structures of poverty.

In this way, Black’s Instagram project dovetails with a tendency toward abstraction in recent art photography. As Walter Benn Michaels (2016: 37–42) details, the most compelling and politically resourceful images of the poor are those that are unpeopled, because they portray economic disenfranchisement, and specifically unemployment, as a structural or formal feature of globalization rather than as a personal affliction. The formal qualities of these works insist on, first, the irrelevance of the viewer’s reaction to the photograph’s meaning and, second, the irrelevance of the photographer’s feelings about the photographed subjects as individuals. This refusal of identification as an organizing principle, in Michaels’ argument, then becomes a homology for how exploitative economies continue despite anyone’s attitudes about them. But Black’s use of abstraction differs in a key way from the art photography of his contemporaries, and from the modernist project more generally, in that it makes no claim for the autonomy of the image. Though they refuse to place a burden on the sympathetic identification of the viewer with the subject of the photo, at every turn they highlight the way that the Instagram feed, and the photos and texts within it, tether the photographer to the subject. Black’s geo-tags locate the impoverished communities in space, but they also track the path of the photographer in space. In an interview (Photowings, 2014), he says that his photographs depend on his ‘personal connection’ to what he photographs, and that his images ‘reflect [my] degree of connection to what [I] photograph’. His tags highlight the interdependence, rather than that unbridgeable difference, between the itinerant photojournalist and the sometimes itinerant, sometimes rooted individuals whom he refuses to represent as individuals.

Tellingly, neither of these positions account for the geo-location of the viewer of his photos. Therefore, Black’s work operates under different assumptions than both 1930s documentary texts and contemporary art photography that hinge on the unbridgeable divide between the artist, the photographic subject, and the audience’s feelings about both. Instead, Black counterintuitively repurposes a device (the mobile phone) and platform (Instagram) that are deeply implicated in widespread, statistically significant impoverishment, so as to take, view, and share photos that provide a bridge rather than a barrier to a photographer’s connection to that poverty. In this way, one might see Black’s silhouetted bodies, which empty out the personality of individual poor people while locating poverty in space, as self-portraits of the photojournalist in the age of social media, when his photographic style and his artistic identity enter a platform awash with other, similar images.

The Poor Photographer in a Crowded Square

Black is clearly ambivalent about this relationship between his feed and the larger Instagram world. For all of the care that he takes to spatially situate the site of his photos, and hence himself, he is noticeably uninterested in one of the more obvious tools: connecting to other accounts. None of his posts of specific places link to other Instagram users or photographers and only his summary maps mention his patrons (Magnum Photos, the Pulitzer Prize Foundation, and MSNBC all helped to sponsor his trips). He meticulously tracks the routes that he follows and the locations that he shoots, and then he refrains from co-locating his digital gallery with other people’s pages, in effect disconnecting it from the rest of the Instagram world to which it contributes. In this regard, it parallels his refusal to use the caption feature of Instagram to include any biographical material about the photographed subjects: in both ways he creates a non-collaborative, closed, if not downright anti-social, social media project.

Ruddy Roye’s When Living is a Protest, however, teems with talk and collaboration. He organizes Living by the hashtag ‘#whenlivingisaprotest’, which he also uses when re-posting other users’ photos of his exhibitions, so that it travels between accounts and creators. He accompanies his original posts with either long, personal accounts of his interactions with the individuals in the photos or with his own occasional poems, composed specifically for the project. Unlike Black, he also explicitly tracks the circulation of his photos and captions through the social media platform, replying to comments left by his followers and offering technical explanations of the equipment he used for particular images. Roye also closely follows the work of other photographers: he frequently comments on and responds to Black’s posts. The result is a grid of photos organized under #whenlivingisaprotest that both tracks the itinerary of the photographer in space and on assignment, as well as the spread of the photographic project in Instagram, on other accounts, and off of the platform into physical exhibition spaces.

Thus, where Black arrives at the ubiquity of 21st-century poverty by way of flat, affectless statistics and their visual corollaries, Roye tracks the paths of documentary through the networking tools of the hashtag, the ‘@’ mention, and the comment function. Each instance of poverty that he photographs is idiosyncratic and tied to an individual, but it is also locatable within a digital collection of other participants. Roye’s project, then, makes visible the collective project of documentary on Instagram without presenting the subjects of his work as transparently readable. In fact, quite the opposite. Though he almost exclusively uses 28mm or 35mm lenses, which requires him to be within several feet of his subject, he often photographs through panes of glass, cyclone fencing, and other semi-transparent barriers that set the subject back from the plane of the viewing screen and intercede between the viewer and photographed subject. For example, in the post ‘Stammering Song’ (Roye 2018), a scuffed window pane separates the camera from the subject of the portrait, while a red neon light reading ‘DELI & GRILL’ reflects onto his body and darkens his face.5 Although his photos for the Associated Press and New York Times tend to focus on dramatic interactions between police and protesters, or the reactions of bystanders to the same, When Living Is a Protest contains very little visual drama.

Roye traces this representational style to Roy DeCarava, whom he cites as a major influence on When Living Is a Protest. Also like DeCarava, Roye largely depends on freelance journalism assignments for his income. By his own account, Roye’s photographic career has, from the beginning, been deeply entwined with the ongoing prospect of unemployment. While jobless in Jamaica, he decided to walk roughly 1000 miles and to take pictures of the island’s indigent population. Several years later, while unemployed in Bedford-Stuyvesant, he passed the time by taking out-of-focus photos of the reflection from his car’s rear-view mirror. This proximity to unemployment works its way into Living, too, which began in 2015 as a series documenting his downtime between stringer assignments, first in Brooklyn and later while walking through neighborhoods in Mississippi, Tennessee, Alabama, and Louisiana. While critics (Cadogan, 2016: 122) herald Roye’s focus on Black life and ‘the unrests now gripping this country’, Living also captures the unrest of joblessness.

Roye claims (Grow, 2014b) that the primary motivation of Living is ‘to express a feeling of invisibility that I have felt for most of my career’. In fact, his presentation of Living on social media offers a way to conflate the social invisibility of his photographic subjects with his own professional struggles. Instagram becomes a viable and necessary platform for When Living is a Protest because it does not depend on his professional employment as a photographer. ‘I have always felt irrelevant and voiceless’, says Roye (2016d). ‘My Instagram feed is my way of talking about the issues that plague not just me but other members of my community’. This is particularly true of his depictions of the poor: he has stated that ‘It’s not a stretch to see [myself] in these images, because I feel like I am seeing me’. ‘Poverty looked like me’, he claims as a refrain across many of his interviews.

It is not a particularly surprising insight that the true content of a social media account’s curated images is, in effect, a self-portrait. Nor is it particularly new in the history of art photography, where the flexibility and performativity of portraits and self-portraits have been mainstays since the late 1960s. However, the particular form that this correspondence takes in Roye’s Instagram account speaks to the interesting possibilities when a photographer places the depiction-of-others inherent to the documentary photo text within the feed-as-self-portrait of Instagram. This is because while Roye is a self-consciously Black photographer, he is also, as the above quotation explicitly states, a self-consciously poor photographer. In fact, Roye’s consideration of the ways in which racial and class identity offer formal possibilities on both sides of the camera differentiates his work from American Geography as well as earlier photo texts.

Those possibilities surface in Living in a number of different ways: for example, his photos often play with the texture of a shallow, geometrically patterned background to highlight the specificity of the location as a thematic undertone of the image itself. In Forgotten People (Roye 2015) and The 53205 (Roye 2016c), Roye positions the subjects in front of monochromatic brick walls. The young Black men who are the subjects of these two photos stand with their chests bared, looking directly into the camera lens with their heads tilted slightly to the viewer’s right. Roye modifies the pose so that they stand in front of prominent cracks that rise from their neck out of the top of the frame, creating the illusion of an ascending rope and noose. This visually ties Roye’s photos to 20th-century images of lynchings: the photographs of individuals in Milwaukee, Wisconsin and Mobile, Alabama produce a visual metaphor for persistent structural racism, a racial violence created by the interaction between these Black men and the built environment.

In other photos, Roye fills in the geometric background with spray-painted portraits, names, or messages that personalize the setting. For instance, the anonymous subway tiles that frame the portrait of Post Man (2016a) are papered over with handwritten, square Post-It notes with cliched slogans like ‘Rise Up!’, ‘Love is all you need’, and, spread over three blue squares directly above the subject’s head, ‘Fuck Donald Trump’, which Roye describes in the captions as ‘seem[ing] to flow over the other like my anger’. Despite the difference in content between the two photos that allude to lynching and the Post-It portrait, they both invoke a longer history of photography’s ambivalent role in the representing African-American bodies and, more specifically, how the seemingly neutral backdrop of the close-cropped, geometrical background prevalent on Instagram, but also in Depression documentary, contribute to the discursive meaning of the photographed subject.

The above photos use the limit of the small, two-dimensional square of the Instagram post, and the photographic traditions that subtend that format, to depict the experience of racialized poverty in the U.S. as both omni-present and isolating, not unlike the social media through which Roye chooses to compose his photo text. Especially in Post Man, the square portrait of a man surrounded by a grid of square Post-it Notes which are, in turn, hung on a grid of subway tiles, reflexively accounts for the photograph’s presentation on Instagram. Not only this, but the content of those Post-it Notes—isolated cliches and line drawings—mimic the cascade of the Instagram feed: rather than each instance containing a sequentially meaningful and necessary piece of a linear narrative, like a serially published story, they are atomized, interchangeable, and modular.

However, Roye also pushes against the limits of the individual Instagram photo and feed by using the captions to reflect on his own position in the world he represents, and the inevitable occlusions in each frame. Each of the images in Living is accompanied by a relatively long account of Roye’s interaction with the subjects of his photos and with his own response to the photo. While the genre of these captions ranges from journalistic descriptions of the setting to clipped, elliptical poetry, they are thematically held together by the author’s reflections on the mobile devices and platforms for self-documentation that are noticeably absent in the actual images. He ends one post titled ‘Black and Blue’ (2017), which depicts a young Black man with the left-side of his face obscured by an American flag, with: ‘And every day we rise, / we see our blue LCD screens / alight / with another casted image / of another Black boy’s dye’. The title references a Black artistic trope that goes back to Louis Armstrong and Ralph Ellison. But Roye brings the ‘Black’ and ‘Blue’ into the present so that they allude to two of the most prominent political slogans of the last decade, ‘Black Lives Matter’ and ‘Blue Lives Matter’. In the process, he links the history of Black artistic production to those movements’ insistence on or erasure of Black life and death—or, as Roye puts it, to the ‘casted image / of another Black boy’s dye’. Both in image and text, the circulation of the ‘casted image’ on ‘our blue LCD screens’ is specifically tied to the mobile media devices that also give rise to When Living is a Protest.

Roye presents an even more complicated narrative in the caption of Post Man. He took the photo in New York soon after returning from Oakland, California, and to some extent he sees it as capturing the mood of the city after the 2016 presidential election. He writes (Roye, 2016a):

As I stood watching other people shuffle slowly from one end of the wall to the other, I heard this quote I was recently told in Oakland.

‘If your art or policy is not for poor people, it is neither radical or revolutionary.’

And then I heard her shouting in anger, complaining at someone that they had stepped in front of her while she was reading. In true New Yorker form, people just stepped to the side without even looking at her. Another woman scanned the wall from left to right, and as she panned her cell phone, I caught his eyes again. They were steely, sharp and filled with emptiness.

So in front of the little crowd I introduced myself and knelt beside Kenan and his empty cup.

Here we find Roye’s aesthetic mission in miniature: it is not just about but also ‘for poor people’ because, as he says, it is for himself. It explicitly invokes the overabundance of images, ‘another woman scanned the wall from left to right, as she panned her cell phone’, along with the dominance of the networked camera in creating and circulating those images. In Roye’s telling, the wall and its messages attract the public’s attention rather than the embodied poor person in front of them. In contrast, his own photo and prose (which both depict the photographer dropping to the level of the subject, rather than ‘stepping to the side’ or ‘scan[ning]’ or ‘pan[ning]’) highlight the person and the empty cup.

Roye’s captions play a key role both in drawing him into the scene of the photograph and alluding to the limits of the dominant style of Instagram photos. Yet in other photos, Roye also attempts to extend the represented world of Living and the kinds of photographic images possible on Instagram. Take for example Plantation Houses, a photograph and caption (Roye, 2016b) from ‘zip code 70560’ that is geo-tagged as taking place on Shot Street in New Iberia, Louisiana. It is one of a number of photographs in Living that locate the subjects by zip code, mirroring one of the organizing principles of American Geography. As the caption reads, the image depicts a ‘group of boys that had gathered at one of the houses’ on the street, ‘dilapidated wooden structures that groaned and creaked down the left-hand side, whispered secrets of a bygone period where small homes housed the weary bodies of tired slaves’.

The single person in the foreground, just off-center in the frame, looks directly into the lens, while two others sit on the house’s stoop in the background, also looking at the camera. The recurring geometric patterns of squares, parallel lines, and smaller frames within the photograph (for example, how the porch roof and poles form a box around the two background figures) echoes some of the previously discussed recurring motifs of Instagram photography, as well as Depression documentary. But the photograph also pushes against both of those stylistic traditions. Instead of using the clapboard siding as a geometrically patterned background (like Evans’s photos), or framing this from the street-facing view of the house and positioning all three individuals on the porch, Roye positions the subjects so that he captures the length of the street and other houses behind the human figures. By refusing to flatten the background of the photo and instead locating these figures on a street, in a neighborhood, the presence of the photographer also becomes a central feature of the photograph. He is not on the street simply passing by but is present on the neighboring porch, part of the scene. In this way, he metaphorically expands the photograph into three-dimensional space, behind the photographed subjects and down the street, but also towards the viewer. He insists that the photographer exists as part of the space that he photographs, and that it extends both into or behind the documentary subjects as well as in front of them.

The Photo Text Unbound

Roye’s and Black’s projects provide two diametrically opposed examples of how the photo text might make the jump from print to social media, one leaning into the geographic specificity but refusing the veneer of personal connection, the other highlighting how the platform tries (but fails) to contain the social world of the photographer and subjects in the feed. When taken together, though, they at least partially answer another long-standing point of contention about the ostensible ethical charge of documentary. As Susan Sontag (1973: 3, 11) writes of photography in general, ‘for many decades the book has been the most influential way of arranging (and usually miniaturizing) photographs, thereby guaranteeing them longevity, if not immortality … and a wider public’. Her early work on the medium most often surfaces in discussions of the ethics of taking a photograph, yet here she explores how ‘the ethical content of photographs is fragile’ and depends on the context of its circulation.6 Sontag is not concerned about the sanctity of the original versus a copy, or the shock of technological reproducibility. After all, a photograph in a book is an image of an image which, for Sontag and her contemporaries such as John Berger (2001), is simply the condition of the image in the 20th century. Instead, Sontag’s quotation above highlights how enclosure in the form of a book undercuts whatever intended democratic intention existed in the documentary impulse: the book circulates to a middle- and upper-class audience that reads the images and words as aesthetic objects rather than representations of the class structure as such (in the case of Black), or as allegories of the photographer’s and subject’s shared impoverishment (in the case of Roye). It is a discomfort with the book as a medium for circulating documentary work that can be found intermittently in the photo texts of the 1930s, too. For example, Agee wanted his and Evans’s work published on newsprint so that it would be cheap enough for sharecroppers to buy a copy, but also so that it would deteriorate and hence avoid the very ‘immortality’ that Sontag saw the book imparting on the documentary text.

Black’s and Roye’s photo texts, in their social-media specificity, offer several, tentative solutions to these ethical, technological, and economic problems. First, they sideline the defining feature of photographic professionalism: compensation. Though both have played central roles in legitimizing ‘Instagram Photographer’ as a legible and self-justifying career name (Black and Roye, for example, were named Time’s Instagram Photographer of the Year in 2014 and 2016 respectively) the social media publication of their work occurs without pay as self-generated user content, and it can be viewed without purchase. As Christian Howard (2019) explains, ‘digital spaces are increasingly used as publishing platforms that are not determined by the traditional economic, national, or linguistic boundaries that govern the print-bound publishing industry’. The economic imbalance governing print photo texts was that professional, compensated photographers and their publishers made money by selling representations of poverty to an urban, middle-class audience. The Instagram model embodied by Black and Roye—namely, the photographer whom identifies with the impoverished subject precisely because neither gets paid—is a novel, though not necessarily sustainable, intervention. Instead of redistributing resources between artist and subject, the amateurism of social media platforms contributes to their shared pauperization. At least, that is, until the publishers and galleries come calling.

The impact of media technology on the economics and aesthetics of the photo text has carried over into other social media platforms, as well. For example, Teju Cole’s Time of the Game, which he published on Twitter, uses the FIFA World Cup tournament as an allegory of the artist’s ambivalent publication through social media. Cole’s experimentation with ‘Twitterature’ is only one example of authors from the traditional world of publishing writing app-lit: Tao Lin, Jennifer Egan, and Jonathan Lethem have all composed fiction specifically for social media platforms. In Time of the Game, Cole assembles fan photographs from around the globe of televisions broadcasting World Cup matches, so that the shared experience of World Cup ‘game time’ overcomes the pesky problem of cultural, linguistic, or geo-political distance. FIFA’s tournament is the occasion for a planetary moment of fellow feeling, and Twitter allows Cole to make this collectivity visible: the beautiful game by way of the digital public square. Yet he ultimately deflates this reading with his final image (Cole, 2014) of the FIFA headquarters in Zurich, Switzerland, captioned: ‘Aw. Winner of the World Cup poses for a picture’. While the players work, FIFA profits, he argues. But Cole stops short of bringing this insight to bear on his own place in the circuit, which in some ways looks far more precarious than the players’s relationship with FIFA. After all, the players get a paycheck while Cole and his global collaborators make visible a collective love of the game, free of charge. The individuals who make a living wage off of Time of the Game work at Twitter, not for the artist.

If each social media photo text documents the increasing symmetry between an impoverished artist and an impoverished subject, the genre more broadly allegorizes how authorship or artist-ship mutate when they participate in Web 2.0 as a primary feature of composition. They extend in time, intermittently popping into an audience’s feed over weeks, then months, then years, and possibly for decades to come. In this way, the social media photo text normalizes the open-endedness of contemporary documentary, which no longer stops on the final page of the book or last wall of the gallery, and which no longer is viewed, read, or interpreted as an autonomous, aesthetic unit. This fragmentation and dispersal of the photo text’s front-end creation and back-end consumption mirrors, at the publication level, the itinerant paths of the photographers who created them. The Depression photo text documented bread lines, but today’s photo text is one.

Notes

- See Allred (2018: n28). A search of the Modern Language Association (MLA) International Database for work published pre-2006, featuring the term ‘documentary’, produces 808 hits. For the period after 2006, the number nearly doubles to 1,581 hits. [^]

- Contemporary photography and video art certainly contains examples of autobiographical connections to economically distressed hometowns. Yet works such as Latoya Ruby Frazier’s Notions of Family (2013), for example, are conceived for the gallery and book. [^]

- Though there are many studies of such media-consciousness in artistic form, the discussion hereafter is most indebted to Kirschenbaum’s (2016) and Hungerford’s (2016) attempts to historicize the interactions between genres and media technologies. [^]

- The catch here is that prioritizing experiential knowledge and the epistemological distance between the rural sharecropper and the urban consumer of documentary tends to re-balance the mission of documentary photography away from political intervention and toward methodological questions about documentary itself. See Fluck (2010). [^]

- Because of issues securing reproduction rights, I provide links to Roye’s Instagram posts in the ‘References’ list rather than include them as Figures. [^]

- Sontag (1973: 82) elaborates later: ‘Because each photograph is only a fragment, its moral and emotional weight depends on where it is inserted. A photograph changes according to the context in which it is seen … on a contact sheet, in a gallery, in a political demonstration, in a police file, in a photographic magazine, in a general news magazine, in a book, on a living-room wall’. For Sontag and Agee, the road from politics to the ‘discourse of art’ is paved with books. See Orvell (1989: 80–82) on 19th-century photography books. [^]

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the Americanist Research Colloquium at UCLA, especially Chris Looby, Carrie Hyde, and Michael Cohen, for their feedback on an earlier version of this essay.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Agee, J and Evans, W 1941 Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. New York: Houghton.

Allred, J 2018 Documentary Work. in Takayoshi, I American Literature in Transition: 1930–1940. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. 303–320. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781108563895.017

Allred, J 2010 Modernism and Depression Documentary. New York: Oxford University Press.

Azoulay, A 2008 The Civil Contract of Photography, trans. Rela Mezali and Ruvik Danieli. New York: Zone Books.

Michaels, W B 2015 The Beauty of a Social Problem. Chicago: University of Chicago Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226210438.001.0001

Berger, J 2001 Understanding a Photograph. in Selected Essays. New York: Pantheon. 215–218.

Black, M 2016 Canton, OH. [Instagram] 7 Sept. https://www.instagram.com/p/BKEGL8tjrwJ/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Black, M 2015 Richmond, VA. [Instagram] 24 July. https://www.instagram.com/p/5hkUE0DFhL/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Black, M 2014 Wire. Exeter, CA. [Instagram] 11 May. https://www.instagram.com/p/n3PMR_DFpw/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Black, M 2016 Salinas, CA. [Instagram] 12 July. https://www.instagram.com/p/BHw81mYDsyu/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Black, M 2019 Over the past months… [Instagram]. 4 June. https://www.instagram.com/p/ByS_Q70Ai6X/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Cadogan, G 2016 Radcliffe Roye. Aperture (June): 122–125.

Cole, T 2014 Aw. Winner of the World Cup poses for a picture. [Twitter] 13 July. https://twitter.com/tejucole/status/488443377667813376 [Last Accessed 11 Aug 2021].

Cole, T 2015 Serious Play. New York Times Magazine, 9 Dec https://www.nytimes.com/2015/12/13/magazine/serious-play.html?_r=0 [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Fluck, W 2010 Poor Like Us: Poverty and Recognition in American Photography. Amerikastudien / American Studies 55(1): 63–93.

Grow, K 2014a #LightboxFF: Matt Black Charts the Geography of Poverty. , 24 April. http://time.com/3809031/lightbox-follow-friday-matt-black/ [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Grow, K 2014b #LightBoxFF: Ruddy Roye and Instagram Activism. , 4 July http://time.com/3810372/lightbox-follow-friday-ruddy-roye/#1 [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Howard, C 2019 Studying and Preserving the Global Networks of Literature. Post45, 17 Sept. https://post45.org/2019/09/global-networks-of-twitter-literature/ [Last Accessed 2021].

Hungerford, A 2016 Making Literature Now. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

Jones, G 2008 American Hungers: The Problem of Poverty in U.S. Literature, 1890–1945. Princeton: Princeton University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1515/9781400831913

Kirschenbaum, M G 2016 Track Changes: A Literary History of Word Processing. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4159/9780674969469

Laurent, O 2014 Lightbox: Matt Black is TIME’s Pick for Instagram Photographer of the Year 2014. , 18 Dec. http://time.com/3615902/matt-black-instagram-photographer-of-2014/ [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Luke, B 2020 Here are the ten most visited photography exhibitions of 2019. The Art Newspaper, 31 March. www.theartnewspaper.com/analysis/here-are-the-2019-s-ten-most-visited-photography-exhibitions [Last Accessed 11 August 2021].

Manovich, L 2017. Instagram and Contemporary Image. Self-published. http://manovich.net/index.php/projects/instagram-and-contemporary-image

Manovich, L 2014 Watching the World. Aperture 214: 48–51.

Marsh, J 2019. The Emotional Life of the Great Depression. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/oso/9780198847731.001.0001

McClanahan, A 2016 Dead Pledges: Debt, Crisis, and Twenty-First Century Culture. Stanford: Stanford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.11126/stanford/9780804799058.001.0001

Murray, S 2018 The Digital Literary Sphere: Reading, Writing, and Selling Books in the Internet Era. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Neel, P 2018 Hinterland: America’s New Landscape of Class and Conflict. London: AK Press.

O’Hagan, S 2018 What next for photography in the age of Instagram? The Guardian, 14 Oct. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/14/future-photography-in-the-age-of-instagram-essay-sean-o-hagan [Last Accessed 12 Aug 2021].

Orvell, M 1989 The Real Thing: Imitation and Authenticity in American Culture. 1880–1940. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press.

Perlow, S 2019 The Handwritten Styles of Instagram Poetry. Post45, 17 Sept. https://post45.org/2019/09/the-handwritten-styles-of-instagram-poetry/ [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Photowings 2014 Matt Black: Lessons in the Field [Vimeo]. Sept 16. https://vimeo.com/106332129 [Last accessed 3 December 2021].

Rabinowitz, P 1992 Voyeurism and Class Consciousness: James Agee and Walker Evans, Let Us Now Praise Famous Men. Cultural Critique 21: 143–70. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/1354120

Roosevelt, F D 1941 The Second Inaugural Address, 1937. in Rosenman, S The Public Papers and Addresses of Franklin D. Roosevelt. New York: MacMillan. 4–5.

Roye, R 2015 Forgotten People. [Instagram] 29 August https://www.instagram.com/p/6-ztxaw8OC/ [Last Accessed 4 January 2022].

Roye, R 2016a Post-Man. [Instagram] 15 November https://www.instagram.com/p/BM2I7WxDeUv/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Roye, R 2016b Plantation Houses. [Instagram] 14 December https://www.instagram.com/p/BOA8SJmAdsz/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Roye, R 2016c The 53205. [Instagram] 20 August https://www.instagram.com/p/BJVRLwqD7Xq/ [Last Accessed 4 January 2022].

Roye, R 2016d When Living is a Protest. Annenberg Space for Photography, 20 October. https://www.annenbergphotospace.org/video/ruddy-roye-when-living-protest/ [Last Accessed 11 August 2021].

Roye, R 2017 Black and Blue. [Instagram] 9 October https://www.instagram.com/p/BaCZNl6FMrA/ [Last Accessed 4 January 2022].

Roye, R 2018 Stammering Song. [Instagram] 6 October https://www.instagram.com/p/BonfVP9l0p9/ [Last Accessed 5 November 2021].

Simon, S 2018. America From the Bottom: Documenting Poverty From Across the Country. NPR Weekend Edition, 27 March. https://www.kcur.org/post/documenting-geography-poverty-us#stream/0 [Last Accessed 10 August 2021].

Stange, M 1989 Symbols of Ideal Life: Social Documentary Photography in America 1890–1950. New York: Columbia University Press.

Sontag, S 1973 On Photography New York: Rosetta Books.

Stott, W 1973 Documentary Expression and Thirties America. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Tifentale, A 2015 Art of the Masses: From Kodak Brownie to Instagram. Networking Knowledge 8: 1–16. DOI: http://doi.org/10.31165/nk.2015.86.399

Wiley, C 2011 Depth of Focus. Frieze, 1 November. https://www.frieze.com/article/depth-focus. [Last Accessed 3 December 2021].