Introduction

This article discusses the life and work of two mid-century British painters, Robert Colquhoun and William Scott. Scott was born in 1913 in the town of Greenock, nestled on the inner reaches of the Firth of Clyde in west mainland Scotland, once famed for the industrial shipbuilding and wool factories that gave employment to the town’s large working-class community. The year after, in 1914, Robert Colquhoun was born just 30 miles to the south in Kilmarnock, a town also rich in industry including textiles, leather and railway engines. Regardless of both artists being born into relative poverty, and both growing up in traditional working-class communities, by the early 1950s they were broadly recognised to be among the finest talent in British painting, having established themselves within London’s elite coteries of avant-garde artists and thinkers. In this paper I discuss how the artists’ working-class origins affected their professional ascent, and, in the case of Colquhoun, eventual descent into obscurity. By employing the examples of these two artists, I aim to show how working-class painters were promoted as part of the state’s strategic (re)construction of British identity following World War II, and that the working-class cultures that they represented were appropriated in support of an image of a united, yet diverse, national cultural landscape.

The reputation of both painters, Colquhoun and Scott, requires repeating for this generation. Despite a recent resurgence of interest in both artists, their reputations still have not regained the heights achieved in their earlier careers, when both were frequently spoken of in the same breath as Francis Bacon and Lucien Freud, both of whom of course still remain internationally acclaimed. Colquhoun experienced the most drastic decline, from celebrated youth, to alcoholism and premature death; and he and his work have received far less attention than is deserving of a painter who was claimed by many in the post-war period to be amongst the most promising of his day. Relative to Colquhoun’s, Scott’s life and career were arguably less radical, and the decline of his reputation less dramatic: he lived to the age of 76, moving between the shores of England, Northern Ireland, and Continental Europe. Yet there are remarkable similarities in the earlier lives of these two artists, and this paper is the first to isolate these two figures side by side. In doing so, it contributes to the growing field of scholarship for both artists, while equally highlighting the centrality of working-class representation—as played out through the arts—in promoting a unified British identity that nonetheless maintained traditional class boundaries. This paper builds upon texts that have explored the question of national identity in British artwork during the postwar period. This notably includes Catherine Jolivette’s Landscape, Art and Identity in 1950s Britain, which examines this question in relation to landscape painting, and with particular, important prominence given to Colonial cultures. This article focuses particularly on relating the construction of collective national identity to working-class cultures, as depicted through the work of prominent artists of working-class backgrounds. By also making prominent the discussion of the British ballet (with which many artists collaborated as costume and set designers), I aim to broaden this discussion to encompass the more inclusive range of artworks and cultural contexts with which artists worked. As I discuss below, just as much as the far-better documented field of painting, the cultures of the ballet (including its administration and artistic collaborations) highlighted the energies that were placed into encouraging the production of artworks that reiterated an idealised and highly curated portrayal of the nation.

‘Unity in diversity’ was the slogan adopted by 1951, when the Festival of Britain put forward a vision of a nation that had recovered from war, and remained world-leading in science, design and the arts. Some of the Festival’s most famous exhibits seemed lifted straight from science fiction. The Skylon, for instance, a vertical structure reaching over 90 metres into the air, appeared to float, a marvel of modern technology and seemingly defying laws of gravity.

Much of the arts, on the other hand, projected a more traditional tone. Instead of scientific discoveries and technological advancements, many of the chosen works emphasised an ancient, productive connection to the land. In a time when Britain was recovering from war and still subject to rationing, the people who lived and worked on the land across the country were here represented as the cornerstone of British productivity.

As I will discuss, this was part of a strategic cultural realignment aimed at fostering unity within the nation. It aimed to install a sense of national pride, while maintaining the distinctions not only between different local cultures, but also between different classes. It should be said that this did not rely on the artists’ own belief in this ideology, and Colquhoun and Scott could both be seen to hold contradictory views.

The Festival of Britain was one way that that this collective identity was presented to the nation, via its enormous revelling crowds, and these tropes of unity in diversity, and communities’ natural connections to the land, were repeated across the cultural output of these post-war years in painting, sculpture, and the ballet. It is with a discussion of the ballet that this article begins. This is an important place to begin not only because of Colquhoun and his long-term partner Robert MacBryde’s work with the Vic-Wells ballet in 1951, in which they represented the working-class cultures of the Scottish Highlands, but also because of how significant the question of national identity had been for this art form in the preceding decades. By describing how the ballet—an early beneficiary of increased state-funding of arts organisations from 1939—acted as a microcosm for the centralised development of national identity in British culture, I aim to show how this agenda came to influence wider arts practice, including the painting practices of Scott and Colquhoun. It is by reaching beyond the narrow confines of media specificity, and acknowledging the broader contexts of all the arts with which artists worked, that we can begin to more fully comprehend the socio-cultural conditions of which the work is a product and artefact. In viewing these artists’ work and careers, I argue that an imagined working-class experience was mobilised to support the state’s post-war agenda of redefining a collective British identity, one that ultimately reinforced class-based divisions and stereotypes.

Donald of the Burthens: Ballet as a Site of Post-War Cultural Renewal

Colquhoun and MacBryde made their debut on the London stage in 1951. Hired as set and costume designers for the ballet Donald of the Burthens, prestigiously staged at London’s Royal Opera House, they worked alongside the highly-renowned Ballets Russes choreographer, Léonide Massine, and followed in the tradition of modernist painters such as Picasso, Léger, and Dali (to name but a few), who had adapted their practice for the ballet, enthusiastically embracing its plastic qualities and potential for spectacle. While the ballet was widely praised, it was, as I argue, inextricable from questions of British national identity in the post-war years. It demonstrates how these artists’ work was embroiled with, and influenced by, debates surrounding the national character, for which working-class (in this case, Scottish working-class) identity was integral.

On 17th June 1942, several years before the Two Roberts (as Colquhoun and MacBryde were commonly known) worked with the Vic-Wells Ballet, the company management attended a meeting in the offices of CEMA (Council for the Encouragement of Music and the Arts). This was the wartime predecessor to the Arts Council, responsible for allocating public funds to the arts that provided cultural distraction for the British population during World War II. Its establishment signalled a shift in the national attitudes towards arts funding, with such state intervention having been widely regarded with suspicion until as late as 1939 (Leventhal, 1990). CEMA was at first part-funded by the Charitable organisation The Pilgrim Trust, but when they withdrew funding in 1942, the Board of Education became CEMA’s sole funder (Leventhal, 1990). From that year, CEMA re-siphoned public funds in favour of professional arts bodies, at the expense of community-led, grassroots initiatives (Belfiore, 2019). Such repositioning reinforced centralised cultural management, giving greater control to this state-supported body to fund, and officially validate, the arts that were deemed favourable.

The Vic-Wells was one such organisation to benefit from CEMA’s changing priorities in 1942, and the purpose of their meeting in this year was to establish a means of ‘closer collaboration’ between the two companies. Here they sought to agree a common direction in which to take their combined cultural endeavours, consequently aligning the ballet company more closely with the aims and pursuits of this state-funded organisation. Unable to attend, the renowned theatre director, Tyrone Guthrie, submitted a letter with his thoughts on the future of the ballet, and its changing purpose:

Our organisation exists for the purpose not of profit-making but of service to the community … Originally this service was intended to be moral (“Keep ‘em out of the gin-palaces”) and was administered locally (Waterloo road) … Conditions are now changed. Surely our service must now be cultural, and administered nationally and publicly. (Guthrie, 1942)

At this precarious moment in wartime Britain, the role of the arts was not merely to keep the poor people of South London off the streets and out the bars, as Guthrie haughtily stated it had previously been. Its impact, he argued, must now be more consequential, crossing the length and breadth of Britain, touching the lives of ordinary British subjects in a meaningful way, while simultaneously supporting and promoting artistic excellence. With increased public funding through bodies such as CEMA (under the influential leadership of John Maynard Keynes who was both personally and professionally invested in the ballet), as well as private patronage stimulated not least by the work of the Ballets Russes who had demonstrated the ballet’s artistic potential, dissemination of ballets indeed began to grow. As Karen Eliot has described, ‘during the war, the exclusivity of ballet’s viewership was challenged and programs were designed to introduce new audiences to the artform’ (Eliot, 2016). As dissemination broadened, the content of ballets became more applicable to a popular audience, with the aim of lessening ‘ballet’s separation from ordinary life’, and ‘emphasizing its usefulness to the common good’ (Eliot, 2016: 4). This inclusive idea of art was resisted by some who maintained their belief in the elitism of the higher arts. However, even this encouragement of greater popular engagement with high culture through audienceship (a principle commonly termed ‘Democratisation of Culture’) was a dilution of earlier ideology that aimed to encourage participation by active involvement (termed ‘Cultural Democracy’), which had been more readily promoted during CEMA’s first two years under the leadership of Dr Thomas Jones (Leventhal, 1990; Belfiore, 2019). The fact that the Vic-Wells meeting took place with CEMA so soon after this ideological shift demonstrates the important role this organisation had under the new strategy that now gave priority to centralised, flagship cultural excellence over community cultural endeavours. Social welfare and the idea of non-vocational adult education through art would still be of primary importance to CEMA and its state-funded Board; though projects would now be less involved with encouraging grassroots participation, than with delivering a top-down, centralised, London-centric perspective, which would be presented to the mass public in increased numbers. Therefore, while the popularisation of this elite classical art form—achieved through wider dissemination and by dealing with issues relevant to the daily life of the proletariat—represented hopes of moving toward a ‘less class-bound society’ (Eliot, 2016: 6), it nonetheless demonstrates the art form of the ballet being employed as a moraliser to promote a ‘greater good’, apparently in service of the nation, and therein mobilised as propaganda to influence a mass public (Eliot, 2016). As I later show, this propagandist undercurrent was still evident during the post-war years, and influenced not only the production of the Two Roberts’ ballet for the Vic-Wells, but the wider public-funded arts that supported Colquhoun and Scott during the 1950s.

Amongst all the arts in Britain, the question of national identity was especially pivotal to the ballet, and it is through this culture, which saw a rapid development from the 1930s onwards, that we can better understand how the notion of British identity infiltrated the arts during the mid-twentieth century. Before the 1930s the English ballet barely existed—having been considered merely a subservient art form to the opera—and it was only after the sudden death of Diaghilev that key figures in British dance returned to London to establish their own schools and companies. The knowledge and experience they had gained from working with the Ballets Russes was palpable, and the spirit of experimentation combined with artistic excellence meant the country could, for the first time, claim to have a national ballet to rival the Russians and the French alike. Following the Ballets Russes and Ballets Suédois, the burgeoning English ballet companies invited collaborations from notable Modernist painters including Edward Burra, Paul Nash, Vanessa Bell, and Duncan Grant (in addition to the Two Roberts). Such collaborations endowed the ballet with contemporary cultural legitimacy, forging a solid connection (with varying degrees of success) to the more highly-respected, better funded, and supposedly more intellectually-rigorous art forms of painting and sculpture. The timing was significant. The perceived intellectual independence of these higher arts, when combined with the ballet’s connection with nationalistic undercurrents, arguably gave further legitimacy to the values that many ballets were funded to spread.

With growing nationalism throughout Europe during the 1930s, the English Ballet’s formation was entwined with heated debates about the national character and collective identity. These debates reached far beyond the ballet to such an extent that this art form became a battleground between sectarian ideologies, as part of a cultural war within the nation. Even the name of the ballet invited fierce debate. Would it be the English Ballet, or the British Ballet? Should it involve solely British contributors? What values should it encompass? Debate on such issues was widespread, and Arnold Haskell (dance critic and director) was one vocal activist against the encroachment of nationalism within art. In his ‘History and Manifesto’ of the national ballet, Haskell fiercely denounced those who sought to contaminate the arts with nationalistic values:

Jingoism of any kind is abhorrent, but most especially artistic jingoism. Our Ballet was founded on Russian Ballet which in its turn was founded on Italo-French Ballet … There is no room for the persons who take sides and who treats an art like an international football match. (Haskell, 1943: 70)

During wartime Britain the issue of contributors’ nationalities became a particular point of dissent. Not only did professional posts as dancers and choreographers provide valuable financial income, they also came with a controversial special exemption from military service. Why, the critics contended, should a ‘foreigner’ be hired in place of British talent, especially at a time of such hardship, and when the role might save a life if offered to a British subject. The matter arose at the Vic-Wells when German-born Kurt Jooss was put forward as the company’s resident choreographer—the following statements were reported in the company’s minute logs:

[Mrs. L’Estrange Malone] said that some criticism had been made of the CEMA proposal to bring the Ballets Jooss back to this country at a time when their dancers, all foreigners, would be exempt from military service when British companies were suffering from loss of personnel to the Forces. (CEMA, 1942)

Despite John Maynard Keynes’s protestations (as Chair of CEMA) over what he considered myopic, parochial attitudes, it was ultimately agreed that British contributors should be given precedent over any foreign talent:

Sponsoring of a foreign Company. [Keynes] deprecated the insular outlook in Art and felt that Ballet, in particular, owed too much to foreign influences for this to be logical. Miss Glasgow confirmed his point that great care was always taken by CEMA that, if foreign artists were employed, no native artist was thereby displaced. (CEMA, 1942)

With xenophobia infiltrating bureaucratic systems—seemingly legitimised through the context of wartime benevolence—the boundaries that defined what was and was not British came into sharp focus. And while in some ways the sense of urgency eased after 1945, the ballet, and the arts more generally, continued to play a critical role in painting a positive portrait of the British character as it was being reformulated for the post-war world. As rationing persisted, representations of local British communities imagined a dignified working-class population. And while in some communities tensions remained high, with persistent political divisions between England, Scotland, Wales, and Northern Ireland, cultural productions helped to promote a wider sense of the nation as one of mutually-respectful unity.

True to the claims of the Vic-Wells to be a cultural service, their repertoire—albeit one frequently danced in the opulent surroundings of the Royal Opera House—encompassed cultural heritage from across the United Kingdom. In 1951, the Two Roberts’ Donald of the Burthens was one such work. Staged alongside Britten’s Billy Budd (which was commissioned for the Festival of Britain the year before as a retelling of Herman Melville’s posthumously published novella, Billy Budd, Sailor (1924)), Donald of the Burthens was based on an old Scottish folk tale that has been likened to the story of Faust (MacDougall, 1910: 68–73).

Donald, the story’s hero, was a poor farmworker in the Scottish countryside, employed by a wealthy nobleman as a wood carrier. Day after day, the story goes, Donald would walk to and from the house, carrying a heavy ‘burthen’ (or burden) of fire wood upon his back. One day he came across a young gentleman—the figure of Death in disguise—with whom he made a pact to escape his life of drudgery and hard labour. Donald is bestowed a career as a physician, and endowed with the increased quality of life that this brings. In the tale, he ultimately proves himself mischievous in trying to outwit Death in aid of his fellow man, rich and poor alike. Donald’s is a pact that suggests the peasant had little pretensions (unlike the egoistical pursuit of limitless knowledge, as in the story of Faust), and in this moralising story, his ambitions seem to be in becoming a member of the lower-middle-class. These are limited aspirations, perhaps, but ones that enable our hero to be a force for good and to help those around him. The story ‘culminates in a battle royal for the life of the king’; and while Donald succeeds in saving the King’s life, Death later ‘takes her revenge by compelling him to dance until he dies’ (The Stage, 1951: 9). ‘He is mourned,’ the Dundee Courier described in its review, ‘but King and cast are compelled to indulge in a wild dance with which the ballet ends, in a whirl of colour, movement and music’ (Dundee Courier, 1951: 3).

Colquhoun, the artist responsible for the ballet’s ‘whirl of colour’, was no stranger to the subject matter of peasants and workers, which had been the focus of much of his artwork since childhood. As a sensitive and thoughtful child, he passed the time observing and sketching, rarely found without his pencils, paints and paper, bought for him by his ‘respectable’ working-class parents as encouragement of his ‘natural enthusiasm’ for art (Bristow, 2010: 7–8). Everyday scenes of his family undertaking routine domestic chores dominated his earliest boyhood sketches, and while his own family was comparatively comfortable in their working-class community, he lived amongst and observed true poverty during these formative years:

He well knew the poverty that was Kilmarnock in those days. The slums existed a stone’s throw away from his own door, and he knew the plight of those who had to call them home. He saw the unemployed thronging the streets. He saw the dole queues, he might even have seen the hunger marchers from Glasgow passing through Kilmarnock on their way to London in the early 1930s. (Malkin, 1972)

Colquhoun’s skills of perception matured through young adulthood, and his early self-directed experiences of scrutinising the lives of the people around him had a discernible influence on his later work. Once based in London, his paintings continued to depict animals and daily interactions between people: simple subject matter, caught in unremarkable moments with vitality and coarse brutality.

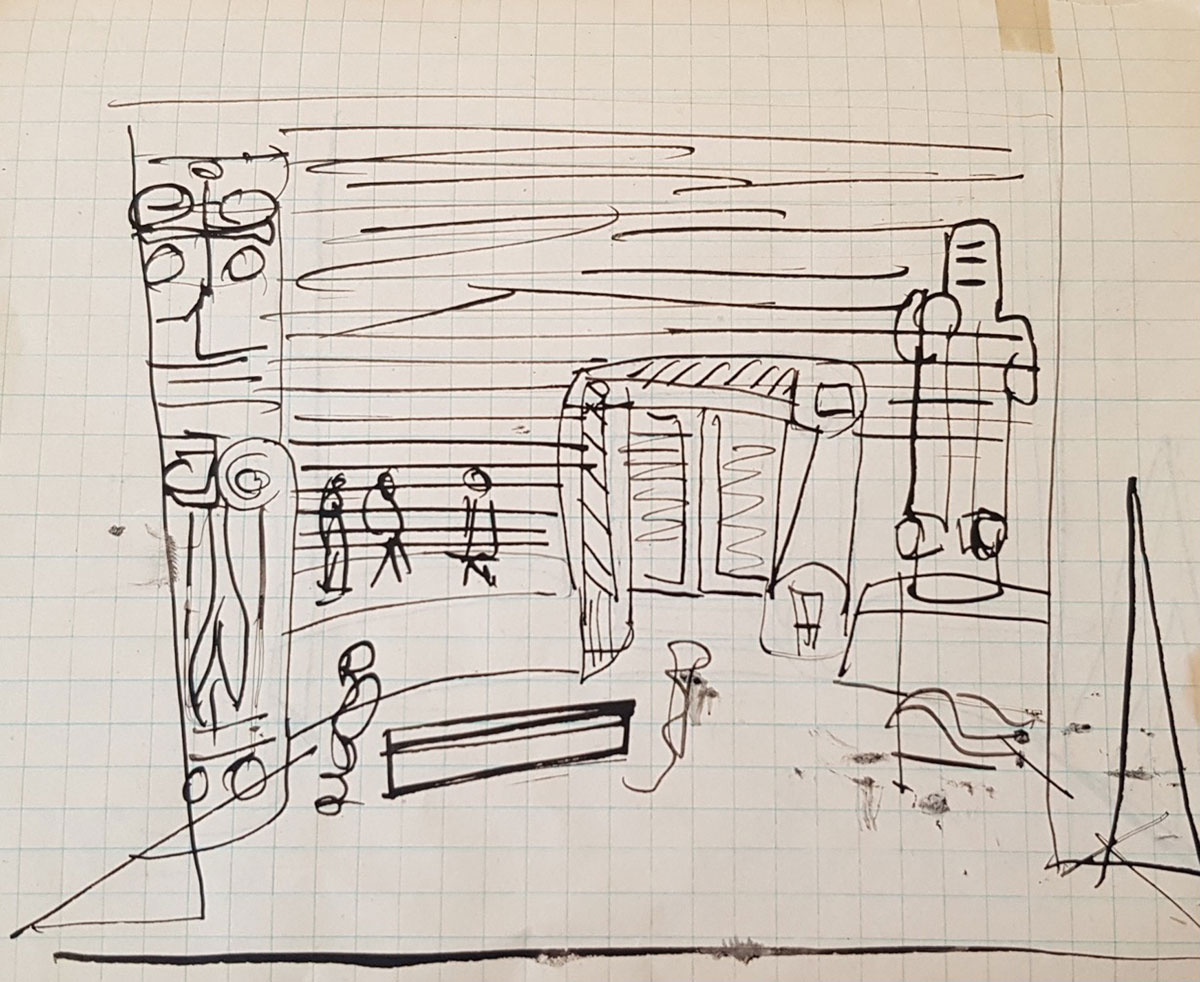

Accordingly, Colquhoun’s sketches for Donald of the Burthens depict more than just clothing designs. The artist’s expressive illustrations are created with attention and care that give character and personality to even the ballet’s peripheral figures. His ‘Peasant Woman’ (Colquhoun and MacBryde, 1951), painted in a modern style with hints of geometric abstraction and bold colour fields, is shoeless, and peering out from beneath layers of ragged cloth. The ‘Three Madmen’ (Colquhoun, c.1950) are imagined as eccentric individuals, painted each in their own slightly erratic pose: ungainly poses similar to those choreographed by Massine, and danced in front of Colquhoun’s striking backdrops (Colquhoun and MacBryde, 1951). The artist’s sketch books suggest that the abstracted stage designs, which we can observe through photographs of the final ballet, were formulated early in his process of development. Coarse ink sketches, scrawled in an exercise book of His Majesty’s ‘Naval & Military Schools’ (possibly remaining from Colquhoun’s brief time in the Royal Army Medical Corps during World War II) show early impressions of the artist’s plans for the scenes (Figure 1).1 Although roughly conceived, the abstract totems that appear in several sketches are evidently the early formations of the megalithic structures painted in a later watercolour (Figure 2), and which were then transposed on to the final backdrop (Colquhoun and MacBryde, 1951). The process highlights how Colquhoun removed the building depicted in the original sketch, reducing the scene to a minimalist landscape. In so doing he rejects the sublime of the vast Scottish landscape, while capturing the essence of modernity via primitivist form.

Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde (1951) Design for Second Scene for Donald of the Burthens [collage, watercolour, ink, and gouache on medium weight, slightly textured, light green paper, sheet], Smith College Museum of Art, Northampton, Massachusetts. © Estate of Robert Colquhoun. All rights reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images.

Such fusion of folk cultures and modernist aesthetic provided the ballet with some ‘striking and unusual features’, as contemporary reviewers observed (The Illustrated London News, 1951: 31). For instance, one reviewer from the Dundee Courier commented enthusiastically on Colquhoun’s bright designs, which he suggested to ‘belie [the ballet’s] grim-sounding scenes’ (Dundee Courier, 1951: 3). The Scottish composer Ian Whyte orchestrated the ‘successful use of the bagpipes and the Celtic “mouth-music”’ (The Illustrated London News, 1951: 31); while Massine ‘blended traditional Scots steps and classic ballet with outstanding success’ (Dundee Courier, 1951: 3). Yet there was undoubtedly more than a hint of caricature about the communities represented in the ballet, with the bedraggled peasants, pipers, and Scotsmen in kilts providing familiar folkloric depictions of the rural Scottish working-classes. The production was part of a wider project to capture the character of the British people—and a concerted effort to represent a diverse array of the nation’s cultures. Yet these safe and stereotyped depictions of Scotland made sure to eschew cultural or political provocation. This was after all a country whose people and culture had endured generations of oppression at the hands of the Westminster-based government, and soon after his arrival in wartime London Colquhoun himself wrote of a persistent ‘antagonism to Scottish culture’ (cited in Bristow, 2010: 111). While frequently framed as nationalists due to their evident pride in Scottish culture, the Roberts did not consider themselves as such, and Colquhoun himself wrote in 1942: ‘Anyway, we have been doing our bit for Scottish painting—we find it trying. It is so difficult to speak of Scottish affairs either political or cultural without immediately being dubbed a nationalist’ (cited in Bristow, 2010: 111). Any noticeable shift in subsequent years towards a more nationalistic stance may well have been in response to the perceived indifference held by the English towards Scottish culture, though as early as 1942 MacBryde anticipated the post-war resurgence in ‘regional’ cultures, of which he optimistically predicted that Scotland would be a key beneficiary (Bristow, 2010: 113). The Festival of Britain’s ambition, therefore, to promote the cultures of Scotland through work such as Donald of the Burthens, may have been, to an extent, an objective welcomed by the Roberts as hesitant advocates of the increased exposure of Scottish culture, even if not the underlying political agenda. Nonetheless, the caricatured folkloric tale of Donald of the Burthens remained a token gesture that gave a nod to the so-called ‘region’ of Scotland, quelling what might have been more radical representations, or conflictual anti-English depictions that might otherwise have resulted through funding to grassroots, rather than flagship, organisations. Scottish working-class cultures were here appropriated in contribution to the broader construction of an image of productive post-war national unity, and whether or not the Roberts supported this ideology, their contribution only helped to legitimise this appropriation.

Parallels in the Lives of Colquhoun & Scott

Colquhoun and his partner, MacBryde, are often discussed as one, their histories intertwined due to how closely they lived and worked together. Meeting as students at the Glasgow School of Art, and attending classes in Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s architectural masterpiece that overlooked the city, one can imagine how the two could have bonded over their shared passion for art, with aspirations of what the future could hold. The education at the school was still at this time a traditional one, and Colquhoun’s early sketches from the period show iterations of conventional subject matter: écorchés (traditional studies of the flayed body’s musculature) that were, on the whole, faithfully studied without any experimental or subversive intent (Yorke, 2001). Such experimentation unfolded later once the artist was established in London, with that city providing creative as well as social freedoms. Homosexuality may have been illegal at the time, but once the Two Roberts resided in the bohemian environs of Kensington and Soho they quickly found themselves amongst like-minded company, and within gregarious social circles that helped also to inspire the excessive drinking for which they soon became infamous. When arriving in London the two had little interest in drink. By their later years alcohol addiction made near-pariahs of them, as they moved ‘rootlessly’ around the South, ‘at times virtually destitute’, and ‘staggering from one drink to the next’ (Clark, 2010: 149). As Brown (2010: 7) describes: ‘By the end of the decade Colquhoun and MacBryde, two of Britain’s greatest post-war painters, were begging friends for money’. Despite frequent attempts by such friends and acquaintances to support them, as Bristow convincingly recounts, the severity of their addiction combined with the increasingly tumultuous nature of their own relationship meant that they quickly became a burden on even the most tolerant and well-meaning Samaritan, and none was ultimately able to divert them from what proved to be a fatal spiral.

It had been a different story in their younger years, and their boozing and bohemian lifestyle helped them to forge close relationships with influential figures such as John Minton, Francis Bacon, Dylan Thomas, and for a time their weekly parties were the gathering place for the city’s most liberated young artists and intellectuals (Clark, 2010). Regularly starting at the Windsor Castle pub in Kensington, they would head en masse to their studio in Bedford Gardens for more drinking, dancing, and to feast on the food prepared in advance by MacBryde. In this moment of their heyday the Two Roberts were known as the ‘Golden Boys of Bond Street’. They enjoyed success selling through the prestigious fine art galleries of Mayfair, supported by their patron Duncan MacDonald of the Lefevre Gallery, and with a growing reputation that extended internationally. When Alfred Barr, the first Director of New York’s MoMA, was sent by the museum to invest in five paintings by the best British painters, he chose pieces by Lucien Freud, Francis Bacon, Edward Burra, and one each by MacBryde and Colquhoun.

Enjoying similar success was William Scott, who was the same age as the Roberts, and born in Scotland only 30 miles from where Colquhoun had grown up. Contrary to Colquhoun’s rough vitality, Scott’s paintings were characterised by their devout austerity, and in his early career he was described as ‘one of the purest, most frank and forthright [painters] of his generation’ (Vogue, 1952: 73). After typical early experiments with portraiture and landscapes, Scott found his most enduring subject in the still life, becoming known, as he himself admitted, as a painter of pots and pans.

The synchronism of these working-class artists from the same Scottish region, mutually overcoming the challenges of their proletarian roots to all become recognised among the most notable painters of their generation, is remarkable. As are the other similarities in their paths to prominence. In his biography of the Two Roberts, Bristow (2010) charts Colquhoun’s development, recounting how James Lyle, his ‘dedicated and zealous’ art master, fostered the young boy’s natural skills and prepared him for entry to Glasgow School of Art. During the Depression, which had created immense financial hardship in this poor community, it was common for young boys to be taken out of school in order to work as apprentices to contribute to the family purse. The young ‘Bobbie’ was no exception, and was removed from Kilmarnock Academy to work with his father at the Glenfield Engineering Works. Aghast by this waste of talent, Lyle secured the financial backing of local patrons to keep the 14-year old in school, allowing him to achieve his place to study at Glasgow School of Art in 1933.

This is closely paralleled by the life of Scott, also apprenticed to his father who was self-employed as a sign- and house-painter. However, unlike Colquhoun, Scott embraced this work that provided certain creativity, financial reward (however meagre), and the opportunity to spend time with his father, who had been absent for much of the boy’s childhood. After encouragement from his family to pursue his artistic skill, Scott then benefitted (also like Colquhoun) from the fortuitous support of his art teacher, Kathleen Bridle, a notable painter who saw potential in the young boy, and helped him to achieve a place at the Belfast College of Art at just 15 years of age. This occurred after the family had moved to the father’s hometown in Northern Ireland, once work became scarce in Scotland. It had been Scott’s father’s dream to see his son go to art school. But fate can be cruel. One evening the year before, the father was passing through the town when he saw a building submerged by flames. He ran to help the family trapped inside the burning building, and tragically fell from a ladder to his death. In an act of remembrance and gratitude for William Scott senior, the local community donated what money it could, raising enough to send the young boy to art school.

On the face of it, the two men, Scott and Colquhoun, continued to walk seemingly parallel paths well into adulthood. They both ended up in London, establishing themselves as painters; both were working largely with still-life and portraits, and both were signalled to be among the best talent in post-war British painting, having both developed their own neo-primitive aesthetic. Their adult circumstances, however, were far from the same. Scott married the young sculptor, Hilda Mary Lucas, whom he met at the Royal Academy art school. He supplemented his painting with a teaching post at the Bath School of Art (having previously set up an art school in Pont-Aven in the South of France), and when finances were tight he had his wife’s family money to fall back on. Neither Colquhoun nor MacBryde had such safety nets. Once their success began to wane due to the sudden rise in influence of the American market (concerned more with popular culture and abstraction than the European styles and subject matter that had dominated the first half of the century), their situation became enduringly precarious. After being ‘ejected’ from the Bedford Gardens studio, he and MacBryde were left without a stable home to live or entertain in, eventually plunging them into isolation, losing the close, vibrant community that they would never fully regain (Clark, 2010: 149; Bristow, 2010: 204). In the end, Colquhoun’s drunken bohemia, which had helped elevate his art and reputation in bohemian London, was also his downfall. What was once appealing of a young, attractive, up-and-coming painter, soon soured in an ageing man. His bohemian life turned out not to be the rite of passage that it so often was for the young middle-classes, but genuine poverty—enduring, and, in his case, inescapable. Colquhoun died at the age of 47 after a rapid decline, ravaged by alcoholism, and visibly burdened by the weight of unfulfilled potential. Recalling a meeting with the artist at his final exhibition at the Whitechapel Gallery (1958), the then Tate Director, John Rothenstein, wrote:

There I met Colquhoun and MacBryde, for the first time sober. When I spoke to Colquhoun of the deep impression made on me by his assembled work, he made no reply, but simply looked at me gravely and I could see tears in his eyes which said as clearly as any words that if he and circumstances had been different he might have achieved infinitely more. (1974)

Scott, on the other hand, continued a stable life into adulthood with family support, easily able to move between the quiet solitude of the Northern Irish countryside and the bourgeois social circles of London. While this was a markedly less raucous London crowd than Colquhoun’s, the paths of the two artists nevertheless frequently crossed, and while Colquhoun was still enjoying his fleeting success he and Scott were often considered amongst the same cluster of emerging British talent.

It was perhaps because of his relatively stable, middle-class conditions that Scott held an uncertain and hesitant connection with his working-class roots. In 1959, for instance, he comprehensively severs his work from his personal history, and uses abstraction to define his work through a formalist lens:

It’s quite true that many of my paintings are saucepans and other kitchen utensils on a bare kitchen table, but this doesn’t mean that I’m particularly attracted to frying pans and saucepans. In fact I think these things are completely uninteresting. That’s why I paint them. They convey nothing. There is no meaning to them at all, but they are a means to making a picture. I’m sure they evoke so little in the spectator’s mind that they really can’t get very confused. They’ve just got to see the painting for its own value. (Whitfield, 2013: 162)

Here Scott presents what might be a surprising interpretation of his own work, which is obsessive in its repetition of these objects. Such repeated forms would happily invite the reading that they were a means to understand or even promote an austere, meagre way of life, and paralleling the repetitive chores of the life of the poor.2 Instead, Scott employs the theory of abstraction to view these objects as pure form, and to remove his pots and pans from any social or political context. Later in life, however, Scott contradicts this earlier statement. In 1986 he stated: ‘The objects I painted were the symbols of the life I knew best … Everyone had a frying pan. It was a feature of Irish life’ (Carty, 1986: 18). Such re-interpretations intimate Scott’s complex relationship with his past, yet his experiences of poverty in his younger life made him more able to employ his primitive aesthetic with greater ‘authenticity’. Scott was influenced by the primitivism of Modernist painters such as Cézanne and Gauguin, but he insisted that his work bypassed these modern, bourgeois interpretations. Instead, he claimed his work went to the roots – the true primitive arts of the ancient ancestors. Simply put, being of working-class heritage gave Scott licence to use primitivism, and to claim that primitive voice as authentic, rather than a modern, intellectualised, middle-class iteration.

The same could be read of much of Colquhoun’s work, and for both artists the notion of the self-reflective, anti-intellectual observer responding viscerally to their subject, was a stereotype that also conformed to their working-class roots. In the case of Scott there was something ancient about his work, as though he spoke the language of long-dead communities, painting for reasons far from the commercial imperatives of modern Britain. For Colquhoun too, his coarse depictions of humanity also seemed to speak a truthful voice of a more ancient tradition.

The two painters may therefore have appeared as natural choices to place within the ICA exhibition entitled 40,000 Years of Modern Art, a provocative examination of the primitivist influence upon the modern aesthetic at the dawn of the high modernist era. Though it took place in 1948, at the height of Colquhoun’s prominence, he and Scott were both overlooked for this exhibition.3 This was just the second exhibition of the Institute of Contemporary Art (ICA), and the ambitious show displayed modern artwork alongside primitive artefacts loaned by institutions such as the Ashmolean Museum in Oxford. Parts of the show were filmed by Austrian filmmaker George Hoellering in his film Shapes and Forms (1950): artworks and artefacts were spotlit and filmed slowly revolving, emphasising aesthetic parallels between modern art and primitive objects. Evident here, from our own point in history, is the modernist fetishisation of Eastern and African cultures, and the primitive influence in the exhibition is exclusively that of those far flung cultures. In contrast, the primitivism of Colquhoun and Scott was more domestic. While influence can and has been drawn to the African-inspired aesthetics of the French post-impressionists and Picasso, their primitivism retains distinct characteristics indigenous to the British Isles. Whether the artists intended this or not, this trope was, as I now discuss, well placed to promote the history of the British land, which became an important political symbol during these years.

“Unity in Diversity”: Representing the People and Land of Britain

Following their acclaimed designs for Donald of the Burthens, the Two Roberts were selected in 1952, alongside Scott, to appear in British Vogue, in the article ‘Painters and Pictures’ by the notorious photographer John Deakin. With their portraits published among the ‘seventeen best painters of the day’, their celebrity in the elite mainstream—a similar audience who would have encountered their work at the Opera House, or through Bond Street galleries—was maintained alongside an eclectic array of fellow British painters. Of the selection, Prunella Clough, John Craxton, Robert Medley and Keith Vaughan represent the most obvious path from European Modernism, with the influence of Picasso and Matisse still dominating the aesthetic treatment of portraits and still life. Equally, de Staël’s school of abstracted landscapes is evident in Victor Pasmore’s blustering Spiral Motif: The Coast of the Inland Sea. Colquhoun’s Two Sisters similarly displays influence from the Continent, via Jankel Adler, and cemented his departure from the concerns of Neo-Romanticism which had dominated his earlier career. Meanwhile, Scott’s timeless still life composition depicts the artist’s growing confidence in his abstracted style; between them, he and Colquhoun represent working-class people and the remnants of their cultures in a manner that rejected the growing ‘Americanisation’ of contemporary western society.

The month of the article’s publication, February 1952, was a pivotal moment in British history. On the 6th day of that month King George VI died. He was succeeded by his 25-year-old daughter, Elizabeth. This issue of Vogue was entitled the “Britannica Number”, exploring the idea of Britishness at the dawn of this new era. The issue’s main feature was entitled ‘Prospect of Britain’, written by notable archaeologist and writer Jacquetta Hawkes, who was best known for her book A Land, which explored British identity through the geographical landscape. The piece emerged indirectly from Hawkes’ work during the preceding years as archaeological advisor for the Festival of Britain. In particular she was involved with the South Bank’s People of Britain pavilion, which told the history of the British people through archaeological findings on British land during the previous century. In her own words, summarising her vast tour of the British Isles, Hawkes wrote:

Everywhere the things that man made and did harmonized with their countryside and were full of local idiosyncrasy—from the way they fastened field gates or baked buns to the way they designed their church towers and spoke the English language. … The explosive development of industrialism has done much to weaken local traditions, to swamp local crafts and products. Yet very much still remains, and it is easy enough to travel the land savouring different types of countryside, different ways of living. (Hawkes, 1952: 59)

She later continues:

From fen to mountain, from east to west of the island is only a few hundred miles, but they are divided also by five hundred million years of time past. The momentous, forgotten events of those remote ages have given diversity to them and to the lands between them; three hundred generations of men and women have laboured to enhance that diversity, to give it character and make it fruitful. (1952: 124)

Here we see, in Hawkes’ sincere yet romanticised view, Britain being defined by and celebrated for its differences: ‘local idiosyncrasies’ observable in the minute gestures that formed daily life. Yet this was at risk, Hawkes warns, from modern industry that sought to homogenise the island’s naturally evolved diversity that had been created by the country’s labouring communities over hundreds of generations. Within this context Deakin’s article forms part of the same project to evoke and celebrate the heterogeneity of British national identity, not only by the subject matter and style of the reproduced paintings, but as much by the painters themselves: Francis Bacon, noted as ‘a collateral descendant of the Elizabethan philosopher’, is praised alongside Scottish working-class artists, including MacBryde, who is described as having ‘laboured as a factory worker for five years’ (Deakin, 1952: 73).

The 1951 Festival of Britain exemplified this trope, and among this hugely ambitious spectacle that dominated artistic, cultural, architectural and technological programming and funding in post-war London, ‘unity in diversity’ was confirmed as a critical theme. As early as September 1948 its development team agreed that the Festival should address:

-

(i) Origins of the British People

… through examples based on results of archaeological research, this section should show how and why we are a mixed race. The characteristics and achievements of the various peoples that settled in Britain would be demonstrated and it would be seen that these persist as the basis of present-day regional differences…

(ii) Expressions of Regional Character which offers scope for the demonstration of dialects, physical types, differences in way of life and other material of this sort recommended by our expert advisors. (Conekin, 2003: 130–131. Emphasis added)4

The ‘regions’ cited here included Scotland, Wales and Northern Ireland, and while cultural differences were highlighted, care was taken for this to remain within safe parameters. The issue of local Welsh and Scottish dialects, for instance, was ultimately considered too contentious, and representations of regional cultures instead focused on ‘productive capabilities’ that would ‘stimulate national renewal’ (Conekin, 2003: 131). This contrasts with the 1851 Great Exhibition, which the 1951 Festival was originally intended to commemorate. Where the Great Exhibition emphasised trade, the final products of industry and their use in Victorian life, in 1951 emphasis was consistently given to the process of industry, and the skills, cultures and people involved in that production (Atkinson, 2012). Process over product; industry in service of the nation; the land and its people providing for the betterment of Britain.

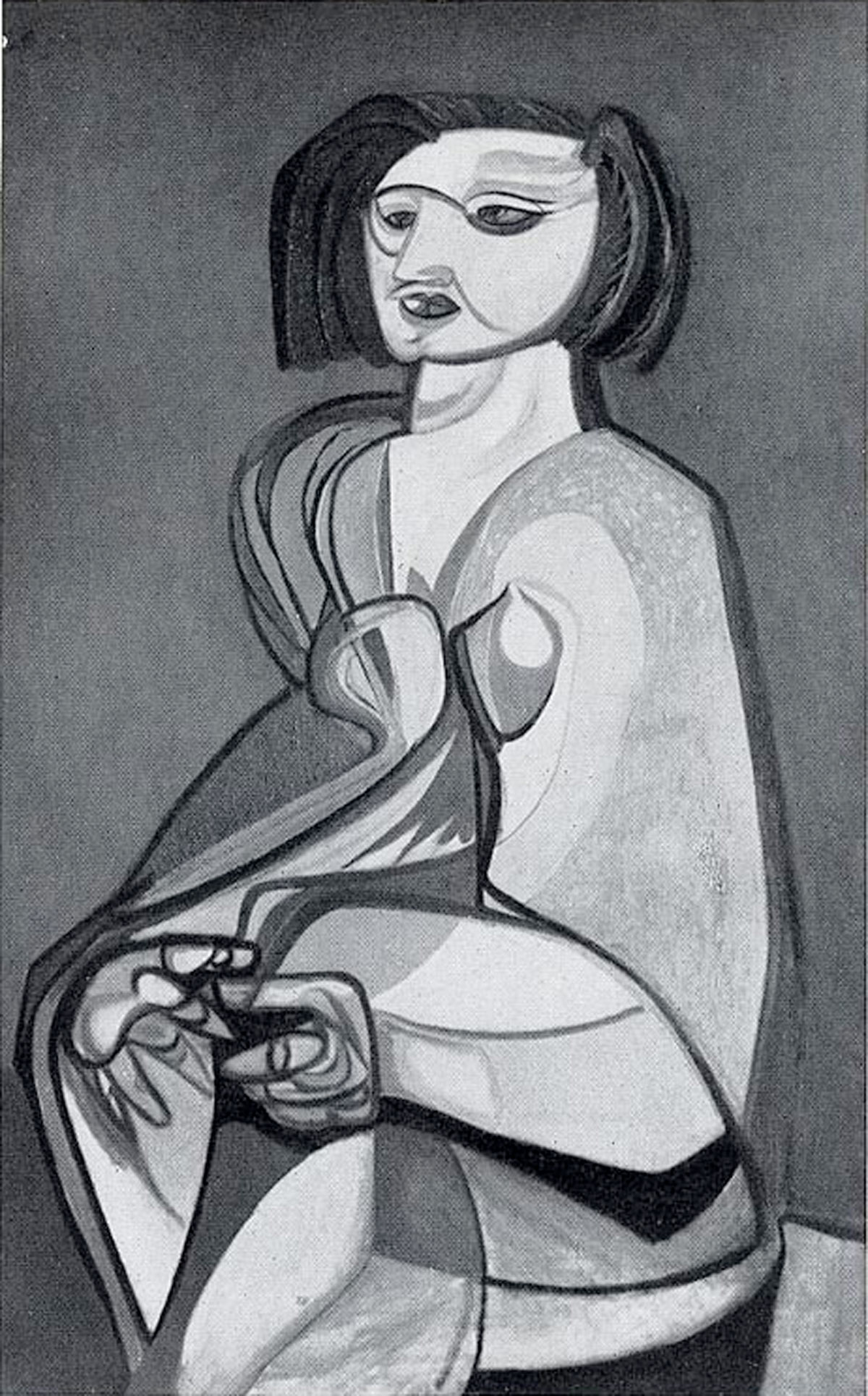

Of the artworks chosen for the Festival’s principal art exhibition, a show entitled ‘60 Paintings for 51’, a good number reflected this ideology. Examples include Lowry’s Industrial Landscape, Julian Trevelyan’s Blast Furnace, Josef Herman’s South Wales, Gilbert Spencer’s Hebridean Memory, Frances MacDonald’s Welsh Singer, and Keith Baynes’s Hop-Picking, Rye. Characteristically, Scott exhibited a still life: a sparse kitchen table with a cast iron skillet, a long fork, and some morsels of food (Figure 3), not directly relating to the process of industry, but nonetheless a portrait of the life of the rural working population. Colquhoun’s piece was a notable exception to this rule. His painting, unrevealingly entitled Figure Painting (Figure 4), portrays an ambiguous, androgynous figure that not only refused to depict process and industry, but was also one of the few to be practically devoid of any definitive social or cultural signifiers. For those familiar with the artist’s work, this may be surprising, because the hidden, typically working-class processes behind an industry, event, or object, had so often been at the centre of his portrayals. In his war paintings, for instance, commissioned by the Ministry of Information (in partnership with CEMA) in 1945, Colquhoun reveals to his viewer a less obvious representation of war than battle-torn fields, valiant soldiers, or tanks and aircraft. Rather he chooses to paint women weaving cloth for the army: an important yet discreet, domestic process, and a traditional, understated working-class profession highlighted in place of the more powerful, contemporary symbols of modern warfare. The image does not condemn the war, but neither does it glorify it. As Sophie Hatchwell has described, Colquhoun was less concerned by the political issues surrounding the war than he was by the human cost and experience of the conflict (Hatchwell, 2019).

In 1951, for Colquhoun’s Figure Painting, this was an imagined experience. Colquhoun was well-known for painting from imagination rather than from life: a method for which he was frequently criticised by Wyndham Lewis. And, despite the ambiguity of the painting, within the very specific context of this exhibition which highlighted the people and history of Britain, what Colquhoun seems to be imagining is a strong, noble, working-class woman. She has thick dark hair cropped short, and a masculine sexuality with flesh exposed from her neck down to her breast. Colquhoun’s Neo-Cubist style gives her strong features, inelegant yet striking. A loose shawl drapes around her body allowing her freedom of movement: both practical and utilitarian, and a physical liberty not afforded to the more tightly bound women of bourgeois society in their constricting fashions. Compare our figure here, for instance, with the women advertising rural attire alongside Hawkes’ Vogue article, with their bodies rigidly held in elegant silhouettes (Figure 5). Colquhoun’s woman could well have come from a different era altogether, yet despite her worn, rugged hands, there is a softness to her eyes that gives her personality and soul that Colquhoun’s figures are so often denied. For, contrary to the assertion that Colquhoun was sensitive to the human experience, by his later years his work is often accused of lacking humanity. Having by this point abandoned the more naturalist, maternal aesthetic of Neo-Romanticism in favour of a harsher Neo-Cubist style, his portraits typically gained an equivalent harshness: in embracing the pictorial qualities of Cubism, the subject’s humanity is sacrificed. David Mellor has compared his post-war work with the angst of Kafka, the antagonism of Lewis’s ‘Tyros’, and related them to a ‘certain kind of bleak Modernism’ seen in Picasso’s anguished portraits of women of the late 1930s. In short, for Mellor, the artist’s pictures betray ‘a universe of despair’ (Mellor, 1987: 56). Wyndham Lewis too, typically supportive of Colquhoun, wrote of his work: ‘It is unusual to find ‘la condition humaine’ attacked, as a subject, by artists in any field in England today’ (Fox, 1969: 400). Such interpretations are understandable, since so many of his portraits, distorted with jet black eyes, seem more like ghostly shadows of human beings. This harshness only matured in Colquhoun’s final burst of productivity before his fatal descent, and Bitch and Pup (1958) stands out in this regard. It is a stark image, a bony carcass of a dog being fed upon by its pup in a corner upon a cold stone floor, with shadows ominously implying the presence of a figure looming above. It suggests Colquhoun’s observation of the cruelty of life and shows a measure of disgust with what he saw.

Figure Painting, despite its anonymity, is a softer, more compassionate study than much of the artist’s wider oeuvre in these post-war years, and this understated portrait of an imagined rural woman is all the more poignant within the context of the Festival. While the exhibition’s context provides Colquhoun’s figure with an imagined history, the painting in return contributes to the narrative of the British connection to the ancient land, and of the noble, dignified working people contributing to the wider good of the nation. In this way, Colquhoun’s work, however inadvertently, conforms to the ideals that the Festival aimed to portray.

Lucy Robinson has described the post war period as a time when the boundaries between the working- and middle-classes were increasingly blurred, and when identities began to be formed by ‘cultural experience rather than by traditional class definitions’ (Robinson, 2007: 10–11). Bristow described a similar social environment in which the Two Roberts found themselves during their early years in wartime London, asserting that as a result of the shared trauma of those who survived the Blitz, long-established class boundaries quickly eroded (Bristow, 2010: 101). While this may at times be the case, as I have shown, the notion of ‘unity in diversity’ remained prevalent within the country’s cultural output, such that, on the contrary, efforts were made to emphasise the differences between the cultures of different classes. In the model set forward by the curatorial choices in all cases described above, including by the Vic-Wells, CEMA, The Festival of Britain, and Vogue, there was a space created for regional diversity. They imagined a way in which the country could evolve into a modern nation without requiring a radical rethinking of traditional class boundaries. Working-class artists could present their cultures and understanding of the world, and be recognised alongside the middle- and upper-classes as equals, as part of a meritocracy that did not threaten the eradication of local identities. For while such local identities, of the working-classes in particular, may have been inextricable from the structures of oppression that had helped to form them over the generations, so too did they embody cherished and authentic regional characteristics that many sought to protect. To be working-class was represented not as something to be escaped from, but something celebrated or even revered. As we can see in the work of Colquhoun and Scott, this often drew on what some might perceive as nostalgic idealism of ‘salt of the earth’ communities, and which stayed away from controversial narrative histories of oppression and violence between the constituent nations of Britain. If Colquhoun and Scott appeared part of a class revolution, it was not only a relatively innocuous one, but one that was in certain regards state sponsored. One in which there was greater access for the working-classes to the means of cultural production, but within the safe boundaries of recognised aesthetic, subject matter, and economic model.

Notes

- For a recent analysis of the Two Roberts’ pacifist war-time art work, see S. Hatchwell (2019), ‘Letters from the Home Front: The Alternative War Art of Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, 1940–1945’. [^]

- Although beyond the remit of this paper, a comparison of the domestic still lifes of Scott and MacBryde is worthy of further study. [^]

- The ICA’s objective was to provide a space to explore emerging trends and innovations in contemporary art. When it was founded in 1946, it remained faithful to the experiments of the European avant-garde, reflected in the ICA’s first exhibition, 40 Years of Modern Art, that foregrounded the enduring influence of Picasso, and of formalist concerns that had dominated Modernist practise. It was in this earlier, less ambitious show that Colquhoun, MacBryde and Scott were shown. [^]

- ‘FB Presentation Panel (48) 4th Meeting, Festival of Britain 1951 Presentation Panel, Minutes of a meeting of the Presentation Panel held at Shepherd’s House, the Sands, near Farnham, on Tuesday 14th September, Wednesday 15th September and Thursday 16th September, 1848’, p.1. Cited in Conekin (2003), The Autobiography of a Nation, pp. 130–131. [^]

Acknowledgements

I would like to acknowledge the support of Oxford Brookes University who have provided time for research, and funds to cover the reproduction of images. I wish to thank Dr Leon Betsworth and Dr Nicolas Lee for their time and efforts spent on the Working-Class Avant-Garde Special Collection, and I am grateful for the feedback from the anonymous peer reviewers, whose comments and guidance were much appreciated. Thanks are also due to the editorial team at the OLH for their patience and guidance.

My thanks to the William Scott Foundation, Five Colleges, Vogue, the V&A, the Robert Colquhoun Estate and Bridgeman Images for allowing reproduction of works included here.

Competing Interests

Alexandra Bickley Trott is the editor of this Special Collection and has been kept entirely separate from the peer review process for this article.

References

Images

Colquhoun, R c.1950 Three Madmen, aka, The Goatmen (costume design for Leonide Massin’es Ballet ‘Donald of the Burthens’ [watercolour, oil paint and ink on paper]. Manchester Art Gallery, Manchester. © Estate of Robert Colquhoun. All rights reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images. Available at: https://manchesterartgallery.org/collections/title/?mag-object-106085 (Accessed: 20 May 2022).

Colquhoun, R and Macbryde, R 1951 Peasant Woman [carbon drawing, ink and gouache on paper]. National Gallery of Scotland, Edinburgh. © Estate of Robert Colquhoun. All rights reserved 2022 / Bridgeman Images. Available at : https://www.nationalgalleries.org/art-and-artists/1065/peasant-woman-costume-design-donald-burthens (Accessed: 20 May 2022).

Colquhoun, R and Macbryde, R 1951 Photograph of set design for Donald of the Burthens, performed at Covent Garden, London [Photograph]. Baron/Hulton Archive/Getty Images. Available at: https://www.gettyimages.co.uk/detail/news-photo/donald-of-the-burthens-played-by-alexander-grant-meets-the-news-photo/519871061 (Accessed: 20 May 2022).

Sources

Atkinson, H and Banham, M 2012 The Festival of Britain: A Land and its People. London; New York: I.B. Tauris. DOI: http://doi.org/10.5040/9780755698523

Belfiore, E 2019 ‘From CEMA to the Arts Council: Cultural Authority, Participation and the Question of ‘Value’ in Early Post-war Britain.’ In: Belfiore, E and Gibson, L (eds.), Histories of Cultural Participation, Values and Governance. London: Palgrave MacMillan. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1057/978-1-137-55027-9_4

Bristow, R 2010 The Last Bohemians: The Two Roberts – Colquhoun and MacBryde. Bristol: Sansom.

Carty, C 1986 ‘Scott Free’ (interview with William Scott) The Sunday Tribune, 24 August: 18.

CEMA and Vic-Wells 1942 ‘Meeting Between Members of CEMA and the Old Vic and Sadler’s Wells Governing Body to Discuss Closer Collaboration.’ 2 June 1942. Unpublished.

Clark, A 2010 British and Irish Art, 1945–1951: From War to Festival. London: Hogarth.

Conekin, B 2003 The Autobiography of a Nation: The 1951 Festival of Britain. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Deakin, J 1952 ‘Painters and Pictures.’ Vogue, February: 72–77.

Dundee Courier 1951. 13 December: 3.

Eliot, K 2016 Albion’s Dance: British Ballet During the Second World War. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199347629.001.0001

Guthrie, T 1942 ‘Closer Co-operation with CEMA: Notes by T Guthrie.’ 17 June. Unpublished.

Haskell, A L 1943 The National Ballet: A History and a Manifesto. London: Adam and Charles Black.

Hatchwell, S 2019 ‘Letters from the Home Front: The Alternative War Art of Robert Colquhoun and Robert MacBryde, 1940–1945.’ British Art Studies, 12. Available at https://www.britishartstudies.ac.uk/issues/issue-index/issue-12/letters-from-home-front (last accessed 1 November 2019). DOI: http://doi.org/10.17658/issn.2058-5462/issue-12/shatchwell

Hawkes, J 1952 ‘Prospect of Britain.’ Vogue, February: 58–69.

Leventhal, F M 1990 ‘‘The Best for the Most’: CEMA and State Sponsorship of the Arts in Wartime, 1939–1945.’ Twentieth Century British History, 1(3): 289–317. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/tcbh/1.3.289

Lewis, W, Fox, C J and Michel, W 1969 Wyndham Lewis on Art: Collected Writings, 1913–1956, edited and introduced by Walter Michel and C. J. Fox. London: Thames and Hudson.

MacDougall, J 1910 Folk Tales and Fairy Lore in Gaelic and English. Edinburgh: J. Grant

Malkin, J 1972 Robert Colquhoun, 1914–1962. Kilmarnock: Kilmarnock Town Council.

Mellor, D and Crozier, A 1987 A Paradise Lost: The Neo-Romantic Imagination in Britain 1935–55. London: Lund Humphries in association with the Barbican Art Gallery.

Robinson, L D 2007 Gay Men and the Left in Post-war Britain: How the Personal got Political. Manchester: Manchester University Press.

Rothenstein, J 1974 Modern English Painters. Vol.3, Hennell to Hockney. London: Macdonald.

Shapes and Forms 1950 Directed by George Hoellering. England: Film Traders Limited.

Sunday Tribune 1986 24 August: 18.

The Illustrated London News 1951 22 December: 31. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/ptj/31.1.22

The Stage 1951 20 December.

Whitfield, S 2013 William Scott: Catalogue Raisonné of Oil Paintings. London: Thames & Hudson.

Yorke, M 2001 The Spirit of Place: Nine Neo-Romantic Artists and their Times. London: Tauris.