Introduction

English Heritage (hereafter EH) is a charity supported by membership subscription, which cares for hundreds of properties and monuments across England that vary in their antiquity and size. Some sites are paid-for entry, many are free to enter. All are cared for with an eye to conservation and continued access for the communities in which they exist as well as a wider visiting public. Many sites that EH care for relate to the history of medieval England—castles and manors, but amongst their numbers are also ecclesiastical sites and deserted medieval villages. Some have substantial standing remains; many comprise earthworks and low walls.

There is a long history to the public curation of the medieval past at properties in care. In Britain, guidebooks for properties in state guardianship appeared from 1917, though publications giving an outline of the history and description of properties emerged from the second half of the 19th century (Gill, 2017: 132–3). All sites have, to a greater or lesser extent, been subject to curation that is entangled in processes and ideologies of conservation. Many medieval standing buildings and associated earthworks in the care of EH have seen such selective curation, undertaken during restoration efforts of the Office of Works and successor departments and organisations such as EH itself, typically when sites were taken into state care. These ideologies stressed the medieval past at the expense of sometimes extensive post-medieval fabric, histories and community associations (Emerick, 2003: 112–3, 147–50).

A primary concern for the historians and curators within EH is to interpret and share the history of properties and their wider landscapes, advocating their stories and communities through multiple media. It is necessary to preface these reflections by noting that the author’s expertise lies chiefly in castles and their landscapes as understood from an archaeological-historical tradition. The author’s training has not been in critical heritage or museum studies. Training aside, in-post experience has exposed the author to wider critical heritage issues.

This paper firstly outlines the groups that are invested in the curation of the medieval: the stakeholders. It discusses how their expectations and aspirations shape the curation of the past before any research is undertaken. Secondly, this paper outlines some of the media used to pursue this goal, providing examples of discrete research outcomes that the curatorial expert has developed. This touches upon recent developments, both in how heritage sites are presented to visitors, as well wider changes in the United Kingdom heritage sector more broadly. Thirdly, it presents a method, the person-centric biographical approach, which the author has deployed to meet challenges. It concludes with some reflections on this approach. To a greater or lesser extent, tools and resources to disentangle the medieval past from the lives of the powerful already exist. The way to use those tools and resources is the topic of discussion here.

Who owns the story of castles?

The central contention of this paper, which in different ways all four sections address, is a conviction that public histories of medieval castles have too often favoured elite narratives and national orientations. This is not a new claim. Scholarship has identified that an elite predilection is at least partly anchored in conceptions of ‘authenticity’ (Dempsey et al., 2020: 365). This echoes Coulson’s remarks, that ‘[t]he subordinate majority [in castles] have left little in the way of relevant documentation’; in other words, there is little evidence which would speak to ‘Castles and the common man’ (2003: 173). This is not a passive defence by Coulson of elite-centrism in castle narratives. Rather, it prioritises the study of documents at the heart of the castle story, reflecting Coulson’s focus as an historian. The broadening potential of medieval archaeology is touched upon later.

The origins of elite-centrism also partly lie in the ownership of, or claims to, castle heritages in the more abstract sense. In the scholarship and passing into heritage narratives, castles have been framed as primarily elite spaces (see below and Goodall, 2011: 3–4). This is a value-laden judgement, echoing the received knowledge of previous generations of scholarship, not an objective point of fact. Centring medieval individual ownership, in the sense of legal property in the present, over collective, community or non-traditional forms of ownership (Hodder, 2010: 865), has meant that the point of departure in the castle story, whether in scholarship or heritage interpretation, becomes one of lordship and the elite individual. In this way, all the other ways of being and belonging in the past and present are excluded in favour of the person who financed a building, held a title or was served by a multitude.

This predisposition to elite narratives has origins in the prevalence of empiricism, both methodology and theory, in professionalised historical practice into the early 20th century. As early as 1848, a House of Commons committee considered the protection of national monuments, ‘which it understood primarily as monuments to illustrious individuals’ (Swenson, 2013: 57). In this way, our interpretation of castles has been entangled with celebrating those who were detectable in the historic record and those who owned them. Thus, interpretation has easily accommodated elite-centric narratives. Yet, the scholarship tells us that the cultural imaginary surrounding castles were not the exclusive domain of architecture itself, nor solely tied to the elites (Wheatley, 2004). In this context those who served and laboured in castles and in the service of castle owners have as much right to have their stories told as those who owned them.

Stakeholders: Expectations and Priorities

It is important to dwell on the composition of the stakeholders involved in the processes of curation. Doing so allows practitioners to understand their aims and to define both success and failures more clearly and with greater granularity, with a view to improving their work. It also allows practitioners to respond to the developments in industry, society and scholarship in a constructive and sustainable way. Recognising the composite nature of the processes of curation, in this instance through a delineation of the stakeholders, can facilitate critical reflection and change.

What factors influence and shape decisions taken at different stages of the curatorial process? How are the challenges of reconciling stakeholder hopes and priorities met? Drawing on the author’s experience, challenges are broken down into two elements: expectations and priorities. On the other side of the equation are stakeholders. Typically, there are four stakeholders who hold expectations and priorities: (1) the visitors to EH sites, both paying and non-paying; (2) the communities in which sites are situated; (3) EH itself; and (4) the researcher or subject specialist, hereafter the ‘curator’: the conservator, historian, archaeologist. These four stakeholders will be addressed in sequence.

The curation of the medieval past in EH tends to manifest most distinctly in projects to re-present or re-interpret a given site, though ad-hoc work is also important. The curator is just one part of a given project workflow; they are one subject specialist. There are others on the team who are assembled on projects: other subject specialists, relating to archaeology and standing buildings, landscapes, interiors and collections, and conservation. There are experts in learning and education, in access, in marketing, in health and safety, in digital media, in outreach, in finance, in site stewardship; very often, there are creative partners, contracted from outside EH; and, there are experts in managing projects and managing experts. Not all these stakeholders are involved in developing the content on an interpretation panel, but the text is very much a product of processes in which they have played a role, from the earliest stages of an interpretation project to its launch across media, and its shelf-life as a finite manifestation of thinking on site histories and interpretations.

(1) Visitors

Visitors to EH properties expect and aspire to have an enjoyable experience when visiting a castle. In simple terms, they want to have a nice time. They also generally want: facilities, like a toilet, a shop and café; to be entertained, individually and collectively; and to learn something (McIntosh & Prentice, 1999: 606–7). Through a third-party agency, EH has segmented its audience, in common with wider heritage and tourism practice (Table 1).

Detail of EH audience segmentation (2019–23), listed by order of significance (1 = highest, 5 = lowest).

| Segment grouping | Motivation, expectation, priority | |

| 1 | Shared explorers | Excited by shared, hands-on learning experiences |

| 2 | Culture seekers | Self-improving day out; high interest in the past and culture. |

| 3 | Entertainment chasers | Ready-made experiences with proven popularity, meeting desire for sense of adventure. |

| 4 | Social seekers | Good times and unique experiences with friends: keen on social interaction. |

| 5 | Comfort zoners | Simple, good value days out to unwind. Low interest in history. |

Different visitors bring different hopes: so-called ‘culture-seekers’ favour traditional approaches to curating the past. They expect to learn about who lived in the castle and about how parts of the castle worked. They understand themselves to be in touch with cultural trends and to possess a hinterland of historical knowledge which they bring to properties and museums. Differently, ‘shared explorers’ value mutual interaction as a central element of the heritage experience: theirs is a collective or group reckoning of the past and its resonances, often, for example, combining learning with reminiscence. Together, these two groups make up the majority of EH visitors and are the focus of this article, but their expectations and priorities in visiting EH properties can be contradictory: what appeals to a shared explorer can be unappealing to a culture seeker and vice-versa.

The challenge of matching curation with audience expectation can be illustrated with an example. At Walmer Castle (Kent), a project replaced a treasured, traditional audioguide for a sophisticated multimedia device. This change elicited disapproval from a segment of visitors falling within culture seekers bracket (Savage & Wyeth, 2020: 997), not simply for the change in technology, but because the new intervention clashed with the site’s ‘atmosphere’. There was a disconnect between the curatorial team’s ambition to refresh the visitor experience on the one hand, with what one audience segment expected a heritage experience to feel like. The feedback regarding the site’s atmosphere, a complex characteristic to define, also touched upon the question of ‘authenticity’, often understood as a central tenet of visitors’ understanding of what makes heritage (Dicks, 2016: 53–5; cf. Lixinski, 2022).

Visitors don’t passively consume the curated past at castle sites: heritage visitors ‘encode’ the information at sites in ways which are meaningful to them, their interests and experiences; in effect, they take part in the construction of their own knowledge, reconciling external information with the immanent package of culture, memory and experience. As Hodsdon (2020) has demonstrated at Tintagel Castle by studying reviews of visits over a summer season, this relationship is complex. One segment of visitors took the castle’s history as a point of departure to creatively imagine the castle’s lost fabric and histories, whereas another, who sought substantiation of the castle’s mythical associations, were in many cases disappointed. This touches upon authenticity from the perspective of visitors, but also reflects how the experiences of authenticity are likely to be highly diverse (McIntosh & Prentice, 1999: 607).

Anecdotal evidence from Walmer Castle and other locations suggest that visitors also bring expectations of things they hope are not on sites. Shared explorers may expect to hear about boiling oil and murder holes, or about archaic sanitation and knightly tournaments, or about murderous nobles and raucous feasting. But they also tend to hope that interpretation will not centre screens and digital media: as an audience, a large portion of their number comprise families with children. Parents and guardians hope to detach their wards from technology by bringing them to sites, at least for a time. As a group, theirs is an experience which only starts with the materials on a site: the interaction between those materials and the visitors is where the experience is created and enjoyed, whether as an exercise in learning, entertainment, or both.

Segmentation is indicative, not definitive: jokes can fair well with both groups, as can serious topics. Both segments expect to understand how the property relates to their understanding of some of the traditional touchstones of popular medieval English history: the Norman Conquest, Richard the Lionheart, Agincourt, Richard III and Henry VIII, for example (Nevell & Nevell, 2020: 109, 120–1; Palmer, 2005).

(2) Communities

The communities in which EH properties reside can be varied in their hopes and expectations, in common with the variety of sites, their settings and local connections. Sites are often cherished by communities as being of a historic significance which speaks to a contemporary importance for places today: in this respect, sites can be emblematic of communities. But the story is not straightforward, just as communities are not singular entities. Antisocial behaviour at properties is an enduring fixture, while several writers have drawn attention to far-right and xenophobic affiliation with several historic properties (Swarbrick, 2022; Williams, 2019; Nevell & Nevell, 2020). This speaks to challenges in the community at large, of which heritage is not distinct.

Historically, approaches by institutions which have shied away from confrontation or who are deemed to have mishandled consultation have alienated portions of site communities in a way which is harmful to all parties. The development of a new public curatorship of the early medieval past at Tintagel Castle (Cornwall) elicited criticism from Cornish nationalists: this is perhaps the starkest illustration of how curatorship of the past is indelibly tied to communities (Greaney, 2020) and how institutions can struggle to meet communities’ varied expectations and priorities.

(3) Institution

The organisation and the project team expect that a visit to a castle will be entertaining and memorable. They want to meet the expectations of the visitor, but also surpass them. The organisation and the project team embark upon a project assuming that visitors want to be challenged as well as entertained, and that they will delight in the curious facts of medieval life as much as want to hear about kings and battles. The institution also believes that people want to learn more about infrequently covered topics, such as stories from below and that which has been excluded from earlier heritage accounts of the past.

This way of thinking is complemented by one of the remits of medieval archaeology: exploration of the past not confined to elite narratives (Hadley & Dyer, 2017: 1–2). The author has tended towards an archaeological, rather than historical-political, exploration of castles because the approach is implicitly not elite-centric. Archaeological narratives also facilitate an exploration of the past which acts against the legacy of heritage in speaking to the construction of national identities and gives scope to the exploration of subaltern stories. It also encourages, with varying degrees of success, curation of the medieval past that is reflective and creative, as the Richmond Castle interactive panel demonstrates (Figure 1).

Photograph of interpretation panel in Cockpit Garden at Richmond Castle (Yorkshire). Photo: © English Heritage. On entering the castle, visitors are given a mock tally-stick (a medieval accounting device) with a central hole. To interact with this panel, the tally-stick is centrally upon a pinwheel and spun. The three circles outline possible scenarios (left), actions (middle) and topics or themes (right).

The medium of the message is important, too: it must be intelligible and relatable, or else it has limited value. There is a place for detailed architectural description, and a place for battles, and a place for visitors to be challenged and to allow reflection, but the message must always be intelligible and relatable.

The institutional priorities of English Heritage can be summarised by drawing on the organisation’s ‘Vision and Values’, as well as strategic documents like its Equality, Diversity and Inclusion Strategy. This records the need to ‘Tell a wider range of stories at sites, online and through blue plaques’ (English Heritage, no date). Relatedly, can visitors with specific access requirements explore the castle in a satisfactory way? For many properties which fall under the internal designation of ‘small sites’—pertaining to the number of visitors, not of the physical extent of properties—the task is prosaic: does current understanding of these properties, and the ways that they have been represented in the past, best reflect the current scholarly consensus, institutional position and visitors’ appetite?

In scholarly circles, castles in the Middle Ages have in the past been deemed the domain of men, which has translated into heritage interpretation. Within the last three decades, one public history of Warkworth Castle (as provided by an EH guidebook) posited that ‘…it was a male-dominated world, and practically all the inmates of a castle such as Warkworth would have been men, the only exceptions being the women who staffed the laundry and a very few attendants upon the countess when she was in residence’ (Summerson, 1995: 9).

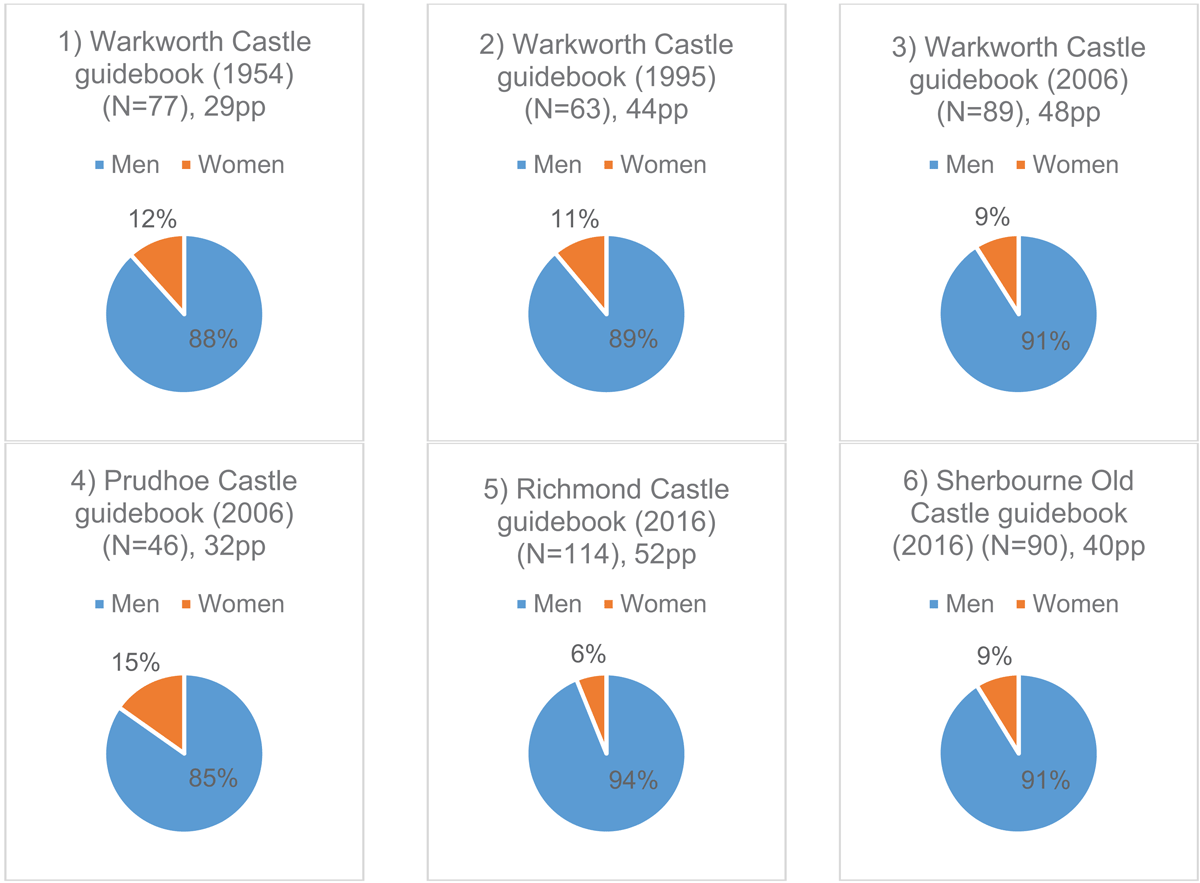

Drawing on work in Dempsey et al.’s 2020 article, it’s possible to identify enduring problems of gender representation, here adhering to a simplistic assumed gender binarism, in EH heritage narratives around medieval castles. The names of individuals were extracted from six EH or antecedent guidebooks and ascribed one of two genders—male and female (Table 2). The sequence of guidebooks (Hunter Blair & Honeyman, 1954; Summerson, 1995; Goodall, 2006) for Warkworth Castle (Northumberland) reveal a decline in the occurrence of named women, while contemporary guides for three other castles in care also evince an overwhelming representation of named men. This echoes findings by Dempsey et al. (2020: 363–5). There are important underlying factors to consider in this data (Nevell & Nevell, 2020: 118), but it is apparent that at least in this more traditional medium of interpretation, drawing on the didactic (curator-as-teacher) and nation-building philosophy of early heritage narratives, there is not a parity of representation.

Representation of named or identifiable men and women (N) in selected EH guidebooks. Guidebooks 2) and 3) contain additional sections on the Hermitage, and guidebook 5) also covers Easby Abbey. Sources: 1) Hunter Blair & Honeyman, 1954; 2) Summerson, 1995; 3) Goodall, 2006; 4) West, 2006; 5) Goodall, 2016; 6) White, 2016.

A further, significant addendum to institutional priorities is perhaps as identifiably idealistic but no less political: how an organisation chooses to spend its money. As a charity in the process of developing autonomy from a block grant of money from government, EH must invest to yield a return that sustains its mission and priorities. For the kinds of properties that the author researches, this means that it is sometimes not possible to install an electric circuit through a site to facilitate new technology for interpretation; elsewhere, it might mean that headsets or tablets as a core element of interpretation are financially unfeasible. This isn’t just about technology: financial constraints inform the choice of panel size and position, the kinds of cabinets used to house collections, and whether part of the interpretation for interactive elements requires pencils and paper, all of which require a budget and long-term maintenance. These considerations are above the expertise of the curator but they work on a project with experts who possess that knowledge; the conversation around the curatorship of the past is crafted by these dialogues.

(4) Curator

Lastly, the curator can be considered. Curators have a code of ethics in terms of representing the past, as well as our own research interests and ideas about what should be prioritised in terms of the stories to tell. Broadly, we want to provide a credible and defensible interpretation of the past to our visitors, as well as our peers in research: in this respect, the curator’s ethics echo those of EH’s institutional priorities. We are keen to reflect developments in the field because the consensus is rarely fixed. We are also people in society, and belong to larger groups: our biases and background inform all the above, and our privilege directs our instincts (Dicks, 2016: 52–3; Lixinski, 2022). The curator’s priorities are common to all public historians and archaeologists: explore the past, do so ethically and share it with others.

Interpretation Media

Having covered some of the challenges in curating the medieval past from the perspective of four stakeholder groups, this paper moves to look at the interpretation media at hand to meet those challenges. For most of the sites the author works on, whether paid-for or free-to-enter, the main interpretative medium is information panels, also called interpretation boards. Boards are popular within EH because they are accessible, hard-wearing, rarely incur short-term maintenance costs, and are largely immune to inevitable deficiencies in technology and infrastructure.

Some panels bear text and images, others facilitate a more interactive interpretation of historic material and places. For example, at Richmond Castle in North Yorkshire, aspects of the castle’s medieval past—the attested presence of a bear-keeper, among others—are co-opted into a light-hearted theatrical task at one of the site panels (Figure 1). Visitors are invited to take fragments of the castle’s history and craft an entertaining vignette. This example of playful learning was not directed by the curator, but rather by the project’s interpretation manager, Joe Savage, and was targeted at the ‘shared explorers’ audience segment (see Table 1). The intervention is located within a somewhat remote part of the castle, the Cockpit Garden, which for at least part of its existence as an enclosed space may have been given over to leisure (Goodall, 2016: 12). Thus, historic figures and activities are blended with interpretation of the fabric to devise a creative and engaging interpretive experience.

Another body of interpretative work centres digital content, chiefly offered through website pages. These can mirror aspects of site-based interpretation but increasingly offer scope for greater interactivity, in-depth storytelling, or a home for discrete items of interpretation which are not necessarily at home on-site.

For example, the website for Stokesay Castle (Shropshire) hosts a discrete element of writing on the life of a later owner of the castle, who researchers have associated with a body of protest poems composed in the reign of Edward III (Wyeth, no date). Digital pathways to interpretation can also facilitate the exploration of parts of the medieval built environment which are inaccessible to visitors and learners with access requirements, as well as opening up certain spaces to international audiences. An interactive reconstruction image by Peter Urmston of a late 13th-century feast at Stokesay presents part of the castle in its medieval past, but also offers layers of additional information through highlighted ‘windows’ which, when selected, lead to pop-ups with additional interpretation (Anon., no date).

Another interpretation item sitting within the realm of digital interpretation is videos created by EH. For example, ‘how to’ videos of an actress playing Mrs Crocombe, head chef at Eltham Palace in the 1880s, which replicate historic recipes. These are extremely popular and dynamic and have garnered in excess of 40 million views on YouTube (English Heritage, 2019a).

A further medium of interpretation falls under the rubric of publications, chiefly guidebooks bought at properties and the members’ magazine distributed through membership lists. Although the author has not written a guidebook, they have made recommendations to edit several existing editions of site guides, as stock numbers dwindle, to capture discrete new research or wider trends in scholarship. For example, the most recent edition of the guidebook on Brougham Castle (Cumbria) incorporates Guy’s (2013–4) research, which suggests that what had been identified as a ‘bottle dungeon’ is better understood as a strong room. In addition, new research was undertaken to establish the extent to which profits from slavery and its legacies underlay the funds used by Charles Henry Foster Barham (1808–78), who held the castle for some time, to undertake repairs in 1848 (Summerson, Truman, Harrison, 1998: 70–1). This reflects a sector-wide trend to interrogate colonial and imperial histories and legacies more closely at properties in care (English Heritage, 2007; Dresser, Hann, 2013; National Trust, 2020). This initial research has spurred a more in-depth examination of the connections of EH castles and the legacies of slavery, which is the subject of a paper of June 2023 (Wyeth, 2023).

A further body of interpretative material, confined to select sites, is audio interpretation: podcasts and audio-guides. The offering is quite different, however. Audio-guides offered as part of the entrance fee to a property or free to members tend to be favoured by culture seekers who are interested in a detailed interpretation of a given site. For example, the audioguide introduced at Warkworth Castle in 2023 explores the site within a three-way conversation between a presenter, a historian and a Warkworth local with family connections to the castle. It is intended to simulate a more relaxed, podcast-inspired conversation, but it also embodies the co-production of different kinds of knowledge and insights on the castle’s history. To a certain extent it challenges the position of curator as gatekeeper of authenticity in a heritage context (Lixinski, 2022).

By contrast, podcasts are, within technological limitations, universally available, and often speak to themes rather than sites; for example, a history of feasting (English Heritage, 2019b). Most recently, the author worked with Cordelia Beattie and Jo Edge of Edinburgh University, on a segment of the biography of writer, Alice Thornton, who briefly resided at Middleham Castle, an EH property in North Yorkshire, during the 17th-century Civil War (English Heritage, 2022). To judge from listening figures, there is an appetite for untold stories: although the feasting episode has been live for a year, it has only half the number of plays (10.7k) compared to the Alice Thornton episode (20.1k).

Lastly, curators aim to contribute towards academic research in their own fields. Thus, they participate in scholarly conferences and seminars, publish papers, apply for funding for projects and support collegial efforts in research agendas, grant assessment and peer review, among others. That dialogue goes two ways: they are also keen to bring in new research, new ideas and new insight into what they do. There are, moreover, further ways, not quite as significant in terms of workload, in which the curator can influence how we present the past: through oversight of educational and learning materials where subject expertise is required (e.g., advice on contents of national curriculum); site visits for members’ events; and, supporting volunteering efforts.

Meeting Challenges: A Biographical Approach

So far, this paper has set out the challenges of curating the medieval past at EH castles. These are summarised below:

Tell an intelligible and relatable story;

Meet and exceed visitor expectations;

Tell little-known stories;

Be faithful to, and give an accurate interpretation of, the evidence;

Bring the curator’s expertise to bear and speak to the present state of research in the field;

Speak to institutional priorities and ambitions.

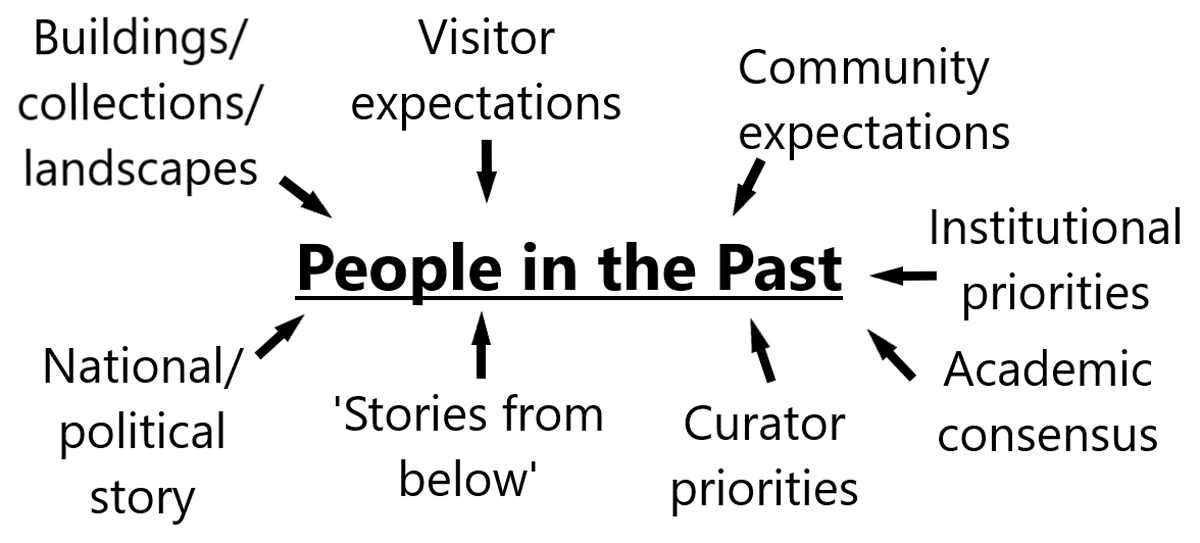

The tools at hand to meet these challenges have also been discussed, along with discrete examples of the work of the curator in meeting those challenges. Now it is possible to turn towards a methodological approach to the challenges. This approach centres biography: the people of the past (Figure 2). Initially this was less of a conscious effort, and more of a developed response to the requirements outlined above, combined with the author having experience of this approach while writing their PhD thesis. In all the interpretation projects worked on, it is an individual’s biography which has acted as a lens through which all the evidence, historical, architectural, archaeological, as well as the expectations and priorities of the stakeholders, are met. It has the advantage of making the community of the castle a core concern; its people an indispensable part of the curated presentation of the past. As mentioned, all too often the interpretation at castles in the care of EH and beyond has focussed on architecture, with a concomitant tendency to centre elite, male stories, and a national political narrative.

This biography-centric take is not unique, and it is not an EH-mandated methodology. This paper will end by outline some of the weaknesses of this approach, but for the moment some examples illustrating it in action will serve to highlight its rationale and strengths.

Consider reconstruction or visualisation images. These are a popular and accessible medium to represent a scene, a view, an aspect of castle life which is otherwise demonstrable through an equivalent thousand words of text. They enable visitors to grasp the life, colour, movement of the past, while also capturing the complexity of lost lifeways, communities, architecture, built complexes, landscapes and environments.

There are hundreds of choices to make when working in collaboration with an artist to create a reconstruction image, through formal briefing documents and ad hoc amendments. These range from the profiles of ditches, the dyes of clothing, the construction of fencing, the configuration of building complexes, to wider decisions regarding the afforestation of the landscape or the development of the adjacent settlement. But beyond resolving uncertainties in the consensus interpretation of architectural and archaeological data, importantly, choices are made when selecting the artist (at the beginning of developing an image), working within their aesthetic and professional style, and medium. Owing to a meeting of these factors—the resolution of archaeological-architectural uncertainties, an artistic style and the motivations for creating a reconstruction—a visualisation of the past is in no small part a creative enterprise (Devine, 2019; Kepczynska-Walczak & Walczak, 2015).

Figure 3 is one of the first pieces of reconstruction the author worked on, at Richmond Castle (North Yorkshire). A key concern in this project was about the view presented and how it related to the visitor looking at the piece. Specifically, an aerial view such as that in Figure 3, while entertaining and informative in some respects, is arguably not relatable—no-one could have seen this view in the medieval past, and it has little bearing on a view of the castle which is accessible in the present. In short, it does not adhere to the biographical, or person-centric ethos advocated for here. For visitors unfamiliar with the site, it’s also a little confusing—several buildings which stand at the castle today, chiefly the 12th-century keep, the tallest and most recognisable part of the castle, do not exist in this reconstruction, so the view does not necessarily aid orientation.

For a closer, more detailed reconstruction—part of Richmond’s Scolland’s Hall—the view presented below in Figure 4 is also unrealistic; one cannot see through walls. Nevertheless, the view and perspective is to a human scale: the artist, JG O’Donoghue worked from a modern photograph of the ruined building, in effect melding present fabric and reconstruction. The position of the interpretation panel that bears this reconstruction is also oriented to closely mirror the perspective of the reconstruction (Figure 5). The boundary between the past and the present is rendered thin. In this way, the visitor’s view echoes a hypothetical medieval one, and the messages about these buildings, their architecture and archaeology, become more relatable and accessible. It prioritises the person interacting with the heritage, rather than making the heritage, as a holistic entirety, the focus of interpretation.

We know that the evidence and detail available for the lives of women is, for most of the medieval era, woeful. The same can be said of most men and children, let alone the spectrum of gender identities. However, by focussing on the person and what we know about them, however meagre, we hope to bring greater relatability and human warmth to the presentation of the past. This is apparent in the stories of several figures whose lives are presented at Richmond Castle. We have Spernellus the bear-keeper (ursarius), attested to in a mid-13th century document, who very likely maintained ursine entertainment at the castle. From the same era, Ymayna, who lived in Richmond town, kept the lord’s horse and hounds, and carried wine to their hunting grounds in the west (Maxwell Lyte, 1916: 14, 159). Her story is difficult to place within the castle, so we meet her via an interpretation panel at the top of the keep, where its elevation gives us a glimpse of the western uplands of Swaledale where she worked. Aspects of personal relationships are also hard to grasp, especially between the rulers and the ruled. The case of Robert the Usher at Richmond, however, gave insight: his name and position suggest he was not a politically or materially powerful individual, but we know he was awarded a plot of land near the castle bridge in the 12th century in recognition of his good service to the Earl (Clay, 1934: 44).

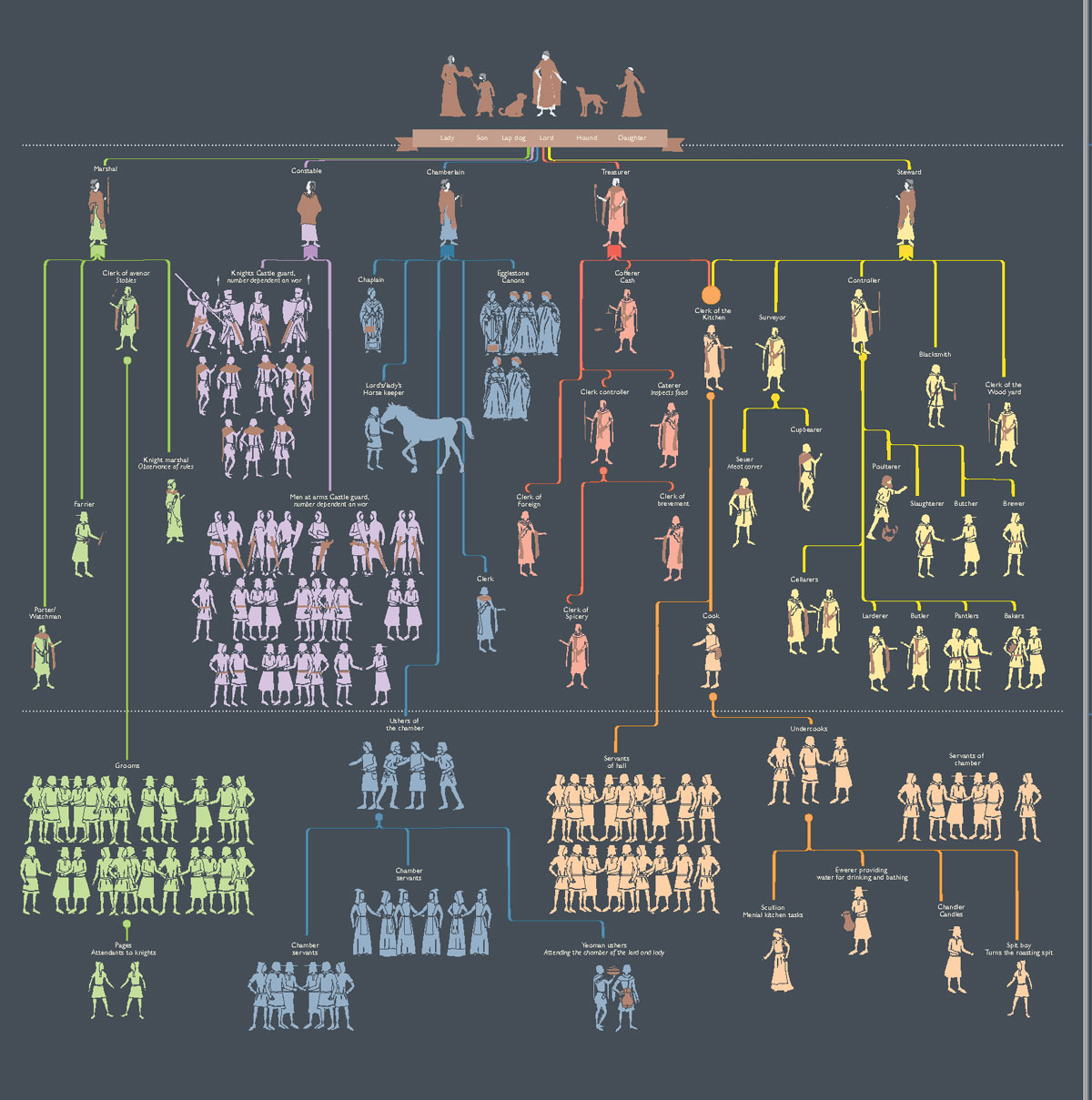

Focussing on biography facilitates the establishment of both a narrative of the hierarchy of the household as well as relations which transcend that hierarchy. A simple way to present the castle hierarchy is through a graphic, which draws on research on castle households in a general sense, and material speaking specifically to this castle. At Richmond, we wanted to capture the sheer number of people who worked at the castle (Figure 6 and Figure 7). This graphic is tied with the small amount of castle collections material, mirroring the household hierarchy. The small collection of material culture sits on alignment (horizontal axis) with the status of individuals (vertical axis) in the castle household graphic. For example, the reused pottery sherds (bottom left of material culture section) shares a horizontal relationship with those in the household (of lower status) who would use it; conversely, the metal keys (top left corner) are associated with officials higher in the hierarchy. Its final form very much represents a collaboration between the historian and the other project subject specialist, Richard Mason, the curator of collections.

The project to represent Warkworth Castle (Northumberland), completed in 2023, is a development of these ideas and approaches. Its interpretation, combining interpretation panels and dynamic sculptural interventions, centres a retinue of historical figures, but rather than being spread across the castle’s entire, 800-year history, they were nearly all contemporaries within a 10-year timeframe centred on the first decade of the 15th century. Rather than tie them to specific spaces within the castle, they are instead associated with routes around the castle. This marks a change in style from fixedness to flow. Thus, in following a trail of panels across the castle site, visitors follow or accompany the historic character, and in doing so, the figures’ world is revealed. These people, and their routes through the castle, are tied to historical events from within their lifetimes—or as close as we can reasonably infer. Moreover, rather than talk about these figures, they talk for themselves. The figures take us along in-the-moment, and visitors walk with them in real time through the castle. One case study illustrates how the biographical approach has been applied in practice at Warkworth. It centres a castle household servant named John del Wardrobe, or John of the Wardrobe.

The final form of John’s presence in the site interpretation ties three ideas together: the historic figure of John, an understanding of castle spaces he worked, and a major national event taking place in his lifetime. We have access to a small number of facts. John is known from two discrete references. In 1382, he attested that his own son was born six days before the birth of a local gentry figure’s daughter, and that he witnessed the baby, Mary Orby, being nursed (Hartshorne & Hodgson Hinde, 1855: 328). In 1418, he is mentioned in a letter from the 2nd Earl to the prior of Durham asking for a place for John in what was essentially a retirement community in the Palatinate (Hodgson, 1899: 45). There are 36 years between these references. Given that both refer to a person who lived in Warkworth and that they were named as ‘John del Wardrobe’, it is assumed that John was in his 20s–30s in the 1380s, and consequently in his 50s–60s in the late 1410s. It is not necessary to assume that he served the entirety of his life in the Percy household or at Warkworth Castle, but it seems feasible to assume his byname was gained through long association with his profession. The wardrobe in this context was an administrative department of the castle household responsible for the storage of clothes and fabrics (Woolgar, 1999: 50).

What of the major national event? Warkworth Castle was home to the Percy family, who in the late 14th–early 15th century were important figures in the national political scene, and very much a leading family of the North of England for much of the late medieval period (Rose, 2002). In the early years of the 15th century, the 1st Earl of Northumberland, Henry Percy (1341–1408), was involved in a plot to remove Henry IV from the throne of England and divide rulership of the kingdom between himself, Prince Owain Glyndŵr of Wales, and the dynastically important English noble, Edmund Mortimer (Davies, 2002: 166–70; Livingston, 2013). The political negotiations leading to the Tripartite Indenture, the 1405 document which attests to this plot, is central to John del Wardrobe’s journey through the castle, from its Great Tower to the earl’s chamber in the castle’s bailey. Over the course of several ‘stops’ at places he would have frequented as an official connected to his profession within the Wardrobe, John discloses aspects of his role in the castle, his personal understanding of what is happening in national politics—including his steadfast loyalty to the Percy family against Henry IV—as well as his own personality. The project has taken the facts of his life and crafted a pattern of speech, grammar, expressions, details about his life and role in the castle, and a narrative tie-in between the big political events and the route through the castle. This is a collaborative effort between the author and a creative writer, Eley Williams, employed through our contracted partners in the Warkworth project, Wignall & Moore. The aspiration is that visitors will feel an emotional affinity with John, whether affection or disdain, as they join him on a short journey across the castle, until the end point of the tour.

How does the journey end? The terminus is embodied by a small sculptural intervention which captures the essence of John as a person from the past, and the heady political events of the day (Figure 8). This terminus also ‘rewards’ the visitor journey, formalising the end of their time with ‘John’. This methodology of intertwinement—of a historic figure, of their place within a historic space, and a specific event within their lifetime—is intended to capture the complexity and nuance of the evidence at hand, as well as of people and their times. It is also hopefully a fun thing to find and explore and will have its own discrete interpretation to facilitate.

There will be five such routes at the castle, each following a specific itinerary and concerning quite different figures preoccupied with historically attested to events; some are tragic, others joyful, others quite mundane (Table 3). This approach seeks to create a space in the present where the experience of the medieval past is anchored in relatable, and perhaps universal, feelings of today—happiness or sadness, for example—but twinned with aspects of the past which are, to a greater or lesser extent, relatable today, such as widespread religiosity; the transition from childhood to adulthood; and the rigorous strictures of class. The characters embrace the full spectrum of castle community, allowing multiple medieval voices to express their spaces, their histories.

Historic figures in the interpretation at Warkworth Castle.

| Figure | Castle spaces | Historic event | Themes |

| John del Wardrobe | Serving and elite spaces | Tripartite Indenture (1405) | Intrigue, personal bonds and service |

| Widow Nawton | Food delivery, storage, preparation | Feast for a new Earl (1416) | Class |

| Eleanor Neville | Stables, chapels, private chamber | Birth of an heir (1418) | Religiosity and magic |

| William Stowe | Posterns, gatehouse, mural tower, bailey | Siege of the castle (1405) | Warfare and anxiety |

| Henry Percy of Atholl | Administration | Death of Hotspur (1403) | Elite identity, mourning and adult masculinity |

Other material interventions in the castle, while respecting its rich fabric, will enhance the experience of visitors with access requirements not currently met on site. The installation of a circular route, proximate to character-led interpretation, audio-guide prompts and ‘neutral’ explanatory information panels in a traditional heritage narration style, touches on aspects of the castle story outside the character-driven trail. In addition, a virtual tour of the Great Tower with interpretive materials, will be accessible to visitors with their own digital devices on-site, but also remotely, opening the tower to the world.

Critiquing the Biographical—Personal Reflections

Before concluding it is necessary to record some limitations to this approach, which are drawn from the author’s experiences. The biographical approach has proven to be optimal for the sites the author has worked on so far, but inevitably each place presents its own challenges which must be met according to the requirements noted earlier.

Though hardly a new idea, the concept of approaching buildings from the perspective of biography occurred during the author’s PhD. The approach provided the clearest way to bring together a wide array of evidence holistically. This approach to rationalising different kinds of evidence through the lens of the biographical was not consciously or explicitly theoretical in outlook, but it is apparent in retrospect that underlying at least part of this interpretation of the past was the work of sociologist Pierre Bourdieu. Interlocking concepts like ‘capital’, ‘cultural capital’, ‘field’, and ‘habitus’ are useful for understanding individual and group behaviours and attitudes, and the decisions made over the course of their lives in rationalizing new experiences (Bourdieu, 1992). The ideas are useful even if used heuristically, as points of departure for interpretation, rather than in a systematic way.

Although the approach of centring the individual—past or present—as the lens through which the curated past is explored has been favoured, it has some deficiencies. There can be a tendency, in the editorial churn of drafting, reviewing, re-writing text, to fall into the habit of telling a story-from-above through the voices of the under-represented in the historic record, the very peoples whose voices we are borrowing to try and tell the story of the past in a different way. This is generally because, where evidence is lacking, for example in the life of John del Wardrobe, the tendency is to ‘fill the blanks’ with the normative (read: uncritically conservative) understanding of John’s life and attitude. For example, we know that he served for some time in the Percy household, so we assume he was fairly happy there. We know the 2nd Earl sought a place for him among the Prior of Durham’s accommodation in John’s twilight years, so we assume that John was well-liked, or that the Earl felt duty-bound, by social convention or by personal fidelity (or both) to look after John.

This presents a risk of taking a reading of the medieval past which frames happy service and cordial relations between those who are served and those who serve as the norm. Criticism of how class relations are relayed in another popular medium of the representation of historic households, British costume drama Downton Abbey (2010–2015), is a useful analogy for this point. The show, set in the early 20th century, depicts relations between aristocrats and their servants in a rural elite residence. Critics have drawn attention to the nostalgic undercurrent of individuals’ relations and biographies. In Downton Abbey working- or middle-class characters, initially expressing either apathy or rancour at the limitations of highly stratified class and the aristocratic family’s privilege, eventually either depart unceremoniously, or are ‘brought around’. Figures like Irish republican, Tom Branson, come to express in many respects incongruous adherence to conservative values around family, marriage and the endurance of legacy wealth, power and privilege (Kevers, 2017; Shachar, 2013). This is a pasteurisation of the past, which neutralises dissenting voices for nostalgic entertainment in the present. Viewers are systematically invited to side with the aristocracy in clashes around class relations and privilege, not only through characters and explicit narratives, but also in narrative mechanisms and structures (Polidoro, 2016).

This depiction of past households, whether hypothetically for John del Wardrobe or in practice in Downton Abbey, is plainly misleading. In the case of John’s life, to a certain extent part of this phenomenon results from the production of history and heritage narratives by, in this case, a single voice, which can act to insulate the status quo from meaningful change (Lixinski, 2022). The curator’s is a voice of authority within a heritage institution, a different but related version of what Emerick (2003: 226) identifies as the archaeologist’s at times contradictory role around scheduled monuments as ‘legislator’ and ‘interpreter’. Emerick’s heritage professionals operate within the legal boundaries of a property and legal obligations around its care. They are influenced by legacies of heritage interpretations which are anchored in the constructed history of place at the point of being brought into care and its initial and ongoing management and conservation, as well as the reception of a medieval past (Emerick, 2003: 272; Johnston & Marwood, 2017: 816–9).

Although we have maintained a faithful interpretation of the evidence, the evidence is in many cases not substantial enough as to represent the fullness of a person’s identity, character, outlook or experience. To supplement this lack of detail in the service of telling a credible story, at times we fall back onto information gathered about the individual within our understanding of their position within a wider group about which we know more; for example, servants, farmers, warriors, or clerks. This mimics aspects of the discipline of prosopography in its aggregation of individuals’ details, seeking what has been called ‘the collective and the normal’ (Keats-Rohan, 2007: 141). By necessity, these ‘stereotypes’ of individuals, constructed from a group identity, are underpinned by a normative view of the past, bereft of personal detail or idiosyncrasy.

This process of removing the nuance of a figure’s personality also happens through a reading of the primary material, an engagement with secondary literature, or the influence of popular medievalisms, leaving us with figures like the haughty teen; the grizzled warrior; the pious countess. In some ways, therefore, we can fall into the trap of telling comfortable and familiar tales, or stories which delight but which do not challenge, share a more nuanced past, or prompt reflection. These are ‘authentic’ figures in that they are loyal to the interpreted evidence deployed to construct a personality but they are also composite or aggregate constructions; evidence speaking to dissent, radical action or thought, can sometimes be removed at the point of creation. This is because the composite, having by its constructed nature an air of inauthenticity and also echoing prosopographical practice, tends to reject unusual evidence in favour of what is similar from elsewhere: evidence which is unusual or rare, as is the case with dissent or radical action or thought for the medieval past, is filtered out. The process becomes a self-fulfilling exercise in affirming a pacified view of the past because of adherence to ‘authenticity’ and a positivist outlook (Lixinski, 2022).

The stories of these figures and their lives are of course individual, but the risk is that these facts only lend a new kind of texture to a familiar tale. When done ineffectively and by relying on the positivist tendency of disciplines like prosopography, the centring of individuals about whose lives the evidence is meagre actually undoes our ability to explore the lives of people in the medieval past, whose experiences might challenge the normative discourse of today on issues of class, gender, sexuality and race, among others; or, more widely, upon individual and collective memories and understandings of the past. Efforts to centre untold stories can tend to depart into the realm of almost pantomime theatricality, as small pieces of recoverable fact are expanded to fill the void of unknowns, leaving an impression of uncomplicated, unchanging individuals.

The question arises as to how these risks can be mitigated. As has been outlined above, the tools to do so already exist. For the project at Warkworth, we have attempted to use creative writing, intuition and artistic intervention in the form of sculptures to enhance the experience of the past, rather than affirm points of fact-oriented narrative (Table 3). The creative flourish lends colour and life to figures and spaces constructed from the past, bypassing the self-perpetuating status quo of ‘authenticity’ which is anchored in what Lixinski (2022) has critiqued as the ‘purity’ of scientific reasoning, or what Carr in 1961 called the ‘cult of facts’ (1990: 9). Instead, it focusses on outcome over process (cf. Johnston & Marwood, 2017: 827–8) or object (Hodder, 2010: 879): a relatable person from the past. Each element which underpins the interventions, the characters, their journeys through the castle, is informed by evidence, but the sum is a creative and exploratory endeavour, which is intended to be open-ended in its interpretation. The audioguide, especially, is explicit in its goal of representing a multiplicity of understandings of Warkworth Castle.

To a certain extent, this initiative has de-centred the curator as the sole, ‘legitimate’ heritage voice. Here, the past is enjoyed in its own terms as spectacle, factual feast or collective delight, but also facilitates reflection for visitors by drawing medieval parallels to modern lives. The results testify to the power of compelling heritage storytelling, informed by the interplay between curatorial work and creative endeavour (i.e. Hodsdon 2020). The conservatism of heritage narratives of the medieval past is not down to individuals alone, as has been made clear, and many challenges endure; but the same can be said of progressive and innovative ways of presenting the past we see today. This paper has made a case for how one approach, centring biographies, though not without its faults, addresses problems with previous presentations of the medieval past at castles.

Acknowledgements

Thanks to the organisers and audience for their comments and questions when this paper was presented at the University of Lincoln in 2022. Additional thanks to Dr Andrew Roberts for insightful suggestions, to Alison Clark for fruitful exchanges of ideas and to the anonymous reviewers for their comments. Any remaining errors and all the opinions expressed herein are mine alone.

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Anonymous n.d. A Feast at Stokesay Castle. London: English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stokesay-castle/history-and-stories/laurence-of-ludlow/#text [Last Accessed 21 February 2023].

Bourdieu, P 1992 Outline of a Theory of Practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Carr, E H 1990 What is History? London: Penguin Books.

Clay, C T 1934 Early Yorkshire Charters IV/V: The Honour of Richmond. Wakefield: Yorkshire Archaeological Society.

Coulson, C 2003 Castles in Medieval Society: Fortresses in England, France and Ireland in the Central Middle Ages. Oxford: Oxford University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780198208242.001.0001

Davies, R R 2001 The Revolt of Owain Glyn Dŵr. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dempsey, K, Gilchrist, R, Ashbee, J, Sagrott, S and Stones, S 2020 Beyond the Martial Façade: Gender, Heritage and Medieval Castles. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 26(4): 352–369. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2019.1636119

Devine, K 2019 Grey Area: The Interpretive Nature of Heritage Visualisation. In: Banissi, E, Ursyn, A, Bannatyne, M W McK, Datia, N, Francese, R, Sarfraz, M, Wyeld, T G, Bouali, F, Venturin, G, Azzag, H, Lebbah, M, Trutschl, M, Cvek, U, Müller, H, Nakayama, M, Kernbach, S, Caruccio, L, Risi, M, Erra, U, Vitiella, A, Rossano, V (eds.) 2019 23rd International Conference Information Visualisation, Paris, France. Paris: Curran Associates. pp. 335–338. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1109/IV.2019.00063

Dicks, B 2016 The Habitus of Heritage: A Discussion of Bourdieu’s Ideas for Visitor Studies in Heritage and Museums. Museums & Society, 14(1): 52–64. DOI: http://doi.org/10.29311/mas.v14i1.625

Dresser, M and Hann, A (eds.) 2013 Slavery and the British Country House. Swindon: English Heritage.

Emerick, K 2003 From Frozen Monuments to Fluid Landscapes: The Conservation and Presentation of Ancient Monuments From 1882 to the Present. Unpublished thesis (PhD), University of York. https://etheses.whiterose.ac.uk/9961/ [Last Accessed 13 April 2023].

English Heritage 2007 English Heritage Properties 1600–1830 and Slavery Connections: A Report Undertaken to Mark the Bicentenary of the Abolition of the British Atlantic Slave Trade. No city: English Heritage. https://historicengland.org.uk/images-books/publications/eh-properties-1600-1830-slavery-connections/eh-properties-slavery-connections-vol1/ [Last Accessed 5 October 2023].

English Heritage 2019a How to Make Butter—The Victorian Way [video]. https://youtu.be/DV7hop4m0YQ [Last Accessed 10 July 2023].

English Heritage 2019b Episode 90—Festive Feasts Through the Ages [podcast]. December 2019. https://soundcloud.com/englishheritage/episode-90-festive-feasts-through-the-ages [Last Accessed 27 February 2023].

English Heritage 2022 Episode 172—Women in Civil War England: Alice Thornton and Middleham Castle [podcast] https://soundcloud.com/englishheritage/episode-173-civil-war-and-childbirth-alice-thornton-and-middleham-castle [Last Accessed 27 February 2023].

English Heritage no date Telling Everyone’s Story: Equality, Diversity and Inclusion (EDI) Strategy. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/siteassets/home/about-us/our-people/jobs/equality-diversity--inclusion/telling-everyones-story---english-heritage-edi-strategy.pdf [Last Accessed 13 April 2023].

Gill, D W J 2017 The Ministry of Works and the Development of Souvenir Guides from 1955. Public Archaeology, 16(3–4): 132–154. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/14655187.2017.1484584

Goodall, J 2006 Warkworth Castle and Hermitage. London: English Heritage.

Goodall, J 2011 The English Castle 1066–1650. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Goodall, J 2016 Richmond Castle and Easby Abbey. London: English Heritage.

Greaney, S 2020 Where History Meets Legend: Presenting the Early Medieval Archaeology of Tintagel Castle, Cornwall. In: Williams, H, Clarke, P (eds.) Digging Into the Dark Ages: Early Medieval Public Archaeologies. Oxford: Archaeolopress. pp. 114–138. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1zcm0qp.14

Guy, N 2013–4 Brougham Castle’s Double-gatehouse, Vaulting Ambition and ‘Bottle Dungeons’. Castle Studies Group Journal, 27: 142–180.

Hadley, D M and Dyer, C C 2017 Introduction. In: Hadley, D M, Dyer, C C (eds), The Archaeology of the 11th Century: Continuities and Transformations. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 1–13. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781315312934-1

Hartshorne, C H and Hodgson Hinde, J 1855 Proofs of Age to Heirs of Estates in Northumberland in the Reigns of Edward III and Richard II. Archaeologia Aeliana, Series 1 (4): 325–330.

Hodder, I 2010 Cultural Heritage Rights: From Ownership and Descent to Justice and Well-being. Anthropological Quarterly, 83(4): 861–882. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1353/anq.2010.0025

Hodgson, J C 1899 A History of Northumberland Volume 5. Newcastle-Upon-Tyne and London: Northumberland County History Committee.

Hodsdon, L 2020 ‘I expected … something’: Imagination, Legend, and History in TripAdvisor reviews of Tintagel Castle. Journal of Heritage Tourism, 15(4): 410–423. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/1743873X.2019.1664558

Hunter Blair, C H and Honeyman, H I 1954 Warkworth Castle, Northumberland. London: Her Majesty’s Stationary Office.

Johnston, R and Marwood, K 2017 Action Heritage: Research, Communities, Social Justice. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 23(9): 816–832. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2017.1339111

Keats-Rohan, K S B 2007 Biography, Identity and Names: Understanding the Pursuit of the Individual in Prosopography. In: Keats-Rohan, K S B (ed.) Prosopography Approaches and Applications: A Handbook. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 139–181.

Kepczynska-Walczak, A and Walczak, B 2015 Built Heritage Perception through Representation of its Atmosphere. International Journal of Sensory Environment, Architecture and Urban Space, 1: 1–15. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4000/ambiances.640

Kevers, L 2017 Re-establishing Class Privilege: The Ideological Uses of Middle and Working-Class Female Characters in Downton Abbey. Anglica: An International Journal of English Studies, 26(1): 221–234. DOI: http://doi.org/10.7311/0860-5734.26.1.14

Livingston, M 2013 Owain Glyndŵr’s Grand Design: ‘The Tripartite Indenture’ and the Vision of a New Wales. In: Brannelly, L A, Henley, G, O’Neill, K (eds.) Proceedings of the Harvard Celtic Colloquium, 33: 145–168.

Lixinski, L 2022 Against Authenticity. International Journal of Heritage Studies, 28(11–12): 1213–1227. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1080/13527258.2022.2134177

Maxwell Lyte, H C 1916 Calendar of Inquisitions Miscellaneous (Chancery) Preserved in the Public Record Office Volume 1. London: His Majesty’s Stationary Office.

McIntosh, A J and Prentice, R C 1999 Affirming Authenticity: Consuming Cultural Heritage. Annals of Tourism Research, 26(3): 589–612. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/S0160-7383(99)00010-9

National Trust 2020 Interim Report on the Connections between Colonialism and Properties now in the Care of the National Trust, Including Links with Historic Slavery. Swindon: National Trust. https://nt.global.ssl.fastly.net/binaries/content/assets/website/national/pdf/colonialism-and-historic-slavery-report.pdf [Last Accessed 5 October 2023].

Nevell, R and Nevell, M 2020 Breaking Down Barriers: The Role of Public Archaeology and Heritage Interpretation in Shaping Perceptions of the Past. In: Gleave, K, Williams, H, Clarke, P (eds.) Public Archaeologies of Frontiers and Borderlands. Oxford: Archaeopress. pp. 16–36. DOI: http://doi.org/10.2307/j.ctv1zckxmq.7

Palmer, C 2005 An Ethnography of Englishness: Experiencing Identity Through Tourism. Annals of Tourism Research, 32(1): 7–27. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1016/j.annals.2004.04.006

Polidoro, P 2016 Serial Sacrifices: A Semiotic Analysis of Downton Abbey Ideology. Between, 7(11): 1–27. DOI: http://doi.org/10.13125/2039-6597/2131

Rose, A 2002 Kings in the North: The House of Percy in British History. London: Phoenix.

Savage, J and Wyeth, W 2020 Exploring the Unique Challenges of Presenting English Heritage’s Castles to a Contemporary Audience. In: Navarro Palazón, J, García-Pulido, L J (eds.) Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean 11–12: pp. 993–999. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4995/FORTMED2020.2020.11421

Shachar, H 2013 Downton Abbey and the Heritage Industry. Overland Literary Journal. https://overland.org.au/2013/04/downton-abbey-and-the-heritage-industry/ [Last Accessed 15 March 2023].

Swarbrick, L 2022 Rosslyn Chapel: Templar Pseudo-history, ‘Symbology’, and the Far-right. In: MacLellan, R (ed.) The Modern Memory of the Military-Religious Orders. Abingdon: Routledge. pp. 21–42. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4324/9781003200802-3

Swenson, A 2013 The Rise of Heritage: Preserving the Past in France, Germany and England, 1789–1914. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139026574

Summerson, H 1995 Warkworth Castle. London: English Heritage.

Summerson, H, Trueman, S, Harrison, S 1998 Brougham Castle, Cumbria. Kendal: Cumberland and Westmorland Antiquarian and Archaeological Society.

West, S 2006 Prudhoe Castle. London: English Heritage.

Wheatley, A 2004 The Idea of the Castle in Medieval England. York: York Medieval Press. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1017/9781846152801

White, P 2016 Sherbourne Old Castle. London: English Heritage.

Williams, H 2019 Wayland’s Smithy and Neo-Nazis. ArchaeoDeath. https://howardwilliamsblog.wordpress.com/2019/08/13/waylands-smithy-and-neo-nazis/ [Last Accessed 15 March 2023].

Woolgar, C 1999 The Great Household in Late Medieval England. New Haven and London: Yale University Press.

Wyeth, W 2023 Connecting Medieval Castles and the Legacies of Slavery: Evidence and Significance from Two English Case Studies, paper presented at Castle Studies: Present and Future: A Symposium to Celebrate Ten Years of the Castle Studies Trust. Winchester, 10 June 2023.

Wyeth, W no date Faithful Subject or Rebel? London: English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/visit/places/stokesay-castle/history-and-stories/faithful-subject-or-rebel/ [Last Accessed 21 February 2023].