Introduction

Conisbrough is a suburban area that feeds into nearby Doncaster and York. Though predominately made up of modern duplex-style residences, one home, Conisbrough Castle, stands out among the rest as a reminder of southern Yorkshire’s rich medieval past. Constructed shortly after the Norman Conquest, Conisbrough Castle was home to the de Warenne family. Hamelin and Isabel de Warenne are the most noted among the residents and kept Conisbrough as a second home from 1129–1202. Little documentary evidence concerning their residency survives, but as they were responsible for the remodeling of the keep, their story is featured above others for visitors to Conisbrough Castle. English Heritage Trust (EH), the current managers of the site, have recounted Hamelin and Isabel’s tenancy through illustrated signage, virtual projections, and the display of a variety of archaeological finds. The goal of EH and their provided resources is to educate visitors on the everyday lives of the 12th century residents and their roles in maintaining an estate and power on location (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 5). However, expanding the narrative beyond the 12th century may better indicate the significance of this particular castle in English history and better demonstrate the connection between the medieval domicile and society. I argue that minimal alterations and additions to the current programming at Conisbrough can illuminate the role of the home as a nucleus for medieval life and activity, which is presently a goal of EH as it explores new forms of engagement at its various sites. Expanding narratives and engagement opportunities will ideally increase visitor understanding of the medieval past and indicate for a diverse audience how the domicile is a consistent setting for reimagining both major historical events and aspects of everyday life.

To best demonstrate the opportunities for pedagogical growth at Conisbrough Castle, this study is divided into three sections. The first of these sections focuses on scholarship by EH staff David Sheldon, Joe Savage, and William Wyeth and their aim to expand learning opportunities. EH prides itself on its continued commitment to visitor education and experience. Its goal for all their properties is to provide ‘fun’ mixed with historical information as the EH Mission Statement notes:

We offer a hands-on experience that will inspire and entertain people of all ages. Our work is informed by enduring values of authenticity, quality, imagination, responsibility, and fun. Our vision is that people will experience the story of England where it really happened (English Heritage, 2004).

The importance of these goals is exemplified by Sheldon and by Savage and Wyeth as they are not only contributing to heritage management discussions in-house but making their research and ideas for program growth available to the wider academic and heritage management-based community (Sheldon, 2011; Savage and Wyeth, 2020). Sheldon has focused on creating play-based activities to help visitors relate to the distant past, while Savage and Wyeth argue for expanding narratives and modes of providing information (Sheldon, 2011; Savage and Wyeth, 2020). Both studies provide arguments for change by first discussing the history of their site, then the current forms of visitor engagement in place, their suggested changes to their engagement, and then by testing their suggested changes at EH sites. I engage with the EH scholarship by first recognizing the kind of changes EH is looking to make at their sites, and then presenting new means of play and education at Conisbrough Castle.

Section two summarizes the de Warenne narrative. The lives of Isabel and Hamelin are focused upon because of the assumed dating of the now reconstructed keep point to their residency. Decorative elements within the structure further the idea of Isabel and Hamelin giving shape to the space, therefore making their tenancy ideal for giving life to the keep and the grounds. Though a successful choice for remembering the medieval past at Conisbrough, the de Warenne couple were not the only ones to call this castle home. In addition to summarizing the story of Isabel and Hamelin, section two examines some of the castle’s other medieval residents and explores how their narratives could be used at the site.

With EH goals and an understanding of the represented narrative in hand, I lastly discuss how the de Warenne narrative is recalled in educational displays at Conisbrough Castle and how those methods can be further developed to align with the new engagement models being used at larger EH sites. I examine the engagements used in the three principal areas of Conisbrough Castle: the inner bailey, the keep, and the EH Gallery. EH uses a consistent artistic style in all their signage and videos, creating a sense of uniformity in the three spaces at Conisbrough. As a means of creating renewed visual interest with their standard style, EH alternates between two-dimensional story boards in the bailey, projected characters and activity tables in the keep, and text-based information presented through a timeline in the gallery. These display methods were chosen to accommodate the environment within the historic spaces and as a means of appealing to the many younger visitors that make their way to Conisbrough Castle. Although in good condition, these presentation methods are 10 years old and do not address some of the narrative-based concerns being considered at other EH sites. According to the scholarship outlined in section one, these displays are limiting because they feature only a Norman narrative, minimalize the role of women in the Middle Ages, and provide little to no tactile interactions. Using the display methods that are in place, I explore ways to develop the historical narrative at Conisbrough that is more in line with what is being attempted at other EH locations.1

Heritage management is based on the concept of public education. It is the goal of this study to recognize the efforts that EH is currently making in attracting a broad audience and consider new ways to celebrate the history witnessed by Conisbrough Castle.

Heritage Management and Considering Program Growth at EH Sites

Before evaluating the presented materials at Conisbrough Castle and areas for growth, it is first essential to recognize the rising concerns and goals being set forth by EH in conjunction with the greater body of scholarship on heritage management. In their 2007 study, Pluralising the Past, G.J. Ashworth, Brian Graham, and J.E. Turnbridge state that ‘heritage is present-centered and created, shaped and managed by, in response to, the demands of the present. As such it is open to constant revision and change’ (Ashworth, Graham and Tunbridge, 2007: 3). Accommodating castle-goers’ expectations for their visit to a castle, which often reflect growing trends within a popular cultural context, makes for a need for changes to visitor engagement at historic sites to maintain relevancy and relatability. Building on the studies of Sheldon, Savage, and Wyeth that demonstrate EH’s recent emphasis on creating more play and on expanding narratives at EH sites, I contend that further development is the way forward for Conisbrough Castle.

Sheldon’s revamp of the Roman-era site at Wroxeter was designed based on the concept of play (Sheldon, 2011). To best get in touch with their inner child, Sheldon’s team of archaeologists, educators, and historians participated in a series of gaming competitions. The team took part in a range of gaming activities, including a board game tournament and a race through the parking lot in shopping carts (Sheldon, 2011). It was the team’s conclusion that fun was best achieved in group activities, through competition, and through physical movement. Thus, new programming for Wroxeter was underway with an emphasis on attracting younger guests with these concepts in mind. The first idea was to create a living museum experience like those offered by York Archaeological Trust (YAT). Recognized for their use of interactive displays, robotics, and tactile experiences at both the Jorvik Viking Center and Barley Hall (a medieval manor house), YAT’s sites are considered the epitome of fun learning (Boniface, 1995; Tuckley and Di Mascio, 2021). Under this presentation method, children visiting Wroxeter would have been invited to don Roman gladiator-style apparel and feel the weight of a recreated sword in their hands (Sheldon, 2011).

This idea was eventually scrapped for a technology-based approach where a PlayStation Portable (PSP) Gaming Console would be used to present the now ruined site as intact and whole to each visitor (Sheldon, 2011). Although programming at YAT’s sites have proven fruitful, incorporating a modern technology at a Roman Wroxeter was selected because of the potential to digitally represent the site in its former glory while simultaneously appealing to the student groups that frequently visit (Sheldon, 2011). The team successfully tested their ideas in their preliminary research, and the next step was consultation with potential younger visitors to the site. EH partnered with a local school group who made several site visits to tour and join in on creating the new educational programming.2 The students aided in creating appealing characters and storylines, taking photos and videos of the site that would be digitized into the game, and then acted as the test group after the concept was made into a game. The new game was made to lead guests through Wroxeter through the perspective of various Roman characters that would earn points as they gathered information at various points of the tour. The process of childlike play solidified the partnership between the adult researchers and student groups and created an official dialogue between heritage managers and future visitor and interpretation users. Furthermore, the EH team confirmed that while the PSP would appeal to school-age guests, parents and adults could also learn to play with the help of their younger travel companions. At Wroxeter, learning is not only fun, but a dialectic conversation between heritage managers and their targeted audience, and the targeted audience and their guardians. Sheldon proves in this study that play is a key ingredient to encouraging visitor enjoyment at the site, and in this case, creating enthusiasm for the historic information. The investment in a technology system like PSP is a major alteration to the programming at Wroxeter that may not be possible at all EH sites. However, the goal of engaging a range of guests, even if the initial intention was geared toward younger visitors, is achieved through this addition at this EH site.

While Sheldon establishes that fun is a must-have for keeping the attention of guests, Savage and Wyeth contend that fun combined with accessible didactic displays might assure greater retention of the presented information (Savage and Wyeth, 2020). Savage and Wyeth focus on budget-conscious means of sharing information, which is significant considering the post-pandemic economy. In comparison to the major makeover of Sheldon’s Wroxeter, Savage and Wyeth have provided smaller, less drastic (but still impactful) means of communication. In their study, they reflect on challenges and different approaches to display and education that will be helpful as they attempt expansions at future EH sites.

EH manages over 70 castles, and Savage and Wyeth recognize that a general or a ‘one size fits all’ program is unachievable across a number of venues (Savage and Wyeth, 2020: 994). Because of the physical condition of each castle, the local and national association of each place, and the EH research team’s desire to present accurate information while appeasing an array of visitors with certain expectations of the site, each castle’s program must be a case-by-case custom design. Savage and Wyeth first consider some of the challenges faced while establishing a custom program and claim that the most common hurdles are overcoming a strictly Norman narrative, choosing instances of social cohesion over times of conflict for the main story, and recognizing if there is a potential ‘Bodiam debate (Savage and Wyeth, 2020: 995; Platt, 2007).’3 Reevaluation of an existing narrative is a challenge because the goal is to add to the story, not replace what has been established (Boniface, 1995: 83). To avoid a misstep in creating new types of engagements, Savage and Wyeth argue that identifying site preservation needs must come first, followed by a choice of medium that can easily be shared and made accessible both on site and at home. To prevent the need to make alterations to the authentic castle site, the media of choice for Savage and Wyeth is the video.

Presently, EH is using their social media platforms to share video content. Videos such as ‘A Mini Guide to Medieval Castles’ uses animations to inform viewers on how a castle is a home in addition to being a fortification (‘A Mini Guide to Medieval Castles’, English Heritage, 2018a). With an increasing amount of medievalesque television shows (including Game of Thrones, Vikings, Reign, and so on), clarifying the multiple functions of a castle and eliminating the one-note story of castles serving defensive purposes (as in the Bodiam Debate, see note 3) broadens the castle-goer’s connection beyond that of fictional entertainment. With this being said, videos like ‘A Mini Guide’ are juxtaposed by ‘How to Take a Medieval Castle,’ a video that emphasizes the defensive aspect of walled baileys and keeps. EH proves in these two videos (which can be utilized at any number of EH properties) that the expected narrative and the new, and alternative narrative can coexist and build upon one another (‘How to Take a Medieval Castle’, English Heritage, 2018b).

Videos can also be used to address lesser acknowledged characters who resided at a given castle. Programs that continue to celebrate the castle as a defensive structure tend toward more male-centric narratives, and videos can act as a platform to showcase former female residents that have previously been a side show to the overall story. Among the sites recalling the lives of medieval women is Goodrich Castle in Wales, who have created a video of modern-day children learning about castle life from former resident, Countess Joan of Valence (What Was Life Like? English Heritage, 2018c). Savage and Wyeth note that although these videos are not without their limitations, they do help in making strides toward presenting a wider array of historical content (Savage and Wyeth, 2020: 996). I have no doubt of the quality of the content or the enthusiasm of the creators behind these videos. My question is whether they are shown on site or made available through a QR code, or if they are only available to those who know to visit the EH website either before or after a visit to a castle.

Issues regarding times of peace and conflict are certainly a concern within Savage and Wyeth’s study, and it is also one I address in my examination of Conisbrough Castle. Within their study, conflict and peace refers to celebrating victors of history, or rather, those that have greater social status (Savage and Wyeth, 2020: 995). Savage and Wyeth also argue for greater representation for women and those of a lower socio-economic status. I expand on their argument in the following section by also considering those resident narratives that are less ideal, or rather, those that face conflict or woe. Stories of the elite medieval person living through tumultuous trials are also worthy of expanding on alongside those that fall within the fairytale ideal.

Recognizing a need to cause minimal alteration or damage to the medieval castle in the creation of new forms of engagements is, without a doubt, the most assured way of ensuring authenticity for castle visitors. Video as a medium for reaching the public avoids any risk to castle infrastructure and provides endless educational opportunities to any audience. What is to be gained from Savage and Wyeth’s examination is a knowledge of the challenges faced in pedagogical growth and that there are issues to be addressed as heritage managers continue to find ways to educate the public while maintaining the setting expected by guests.

Sheldon’s emphasis on creating new forms of engagement and fun in conjunction with Savage and Wyeth’s recognition for addressing different narratives through new media lays the foundation for what can be done to engage visitors at Conisbrough Castle. The following sections of this study address the recognized narrative at Conisbrough and those that are secondary, as well as proposed means of growth based on the presentation methods considered here in section one. Fun and enjoyment are essential for bringing in visitors, but fun is established when historical foundations are concretized, and the two concepts brought together. Based on the current presented narratives and displays at Conisbrough, there is certainly potential for an expansion of historical content with simultaneous visitor amusement.

A History of Conisbrough Castle

The narrative of Isabel and Hamelin de Warenne featured at Conisbrough Castle is summarized in the EH Conisbrough Castle Guidebook and Stephen Johnson’s archaeological report. The couple inherited the castle in 1148 and retained possession until they died only months apart in 1202 (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 27; Johnson, 1984: 5). Although they kept a home in Lewes as their primary residence, Conisbrough was likely updated (especially the keep) during Hamelin and Isabel’s ownership and maintained by a steward, Otes de Tilly, in the couple’s absence. Both Johnson’s account of the castle’s history and the EH Guidebook note that there is little known about Hamelin and Isabel, but their royal familial relations made them present for the activities of the court. The history of Conisbrough is therefore presented through highlights of major historical events in England during Isabel and Hamelin’s 54-year ownership of the castle, through its architectural features, and through the reimagined lives of Hamelin and Isabel that are based on comparable figures about whom more is known.

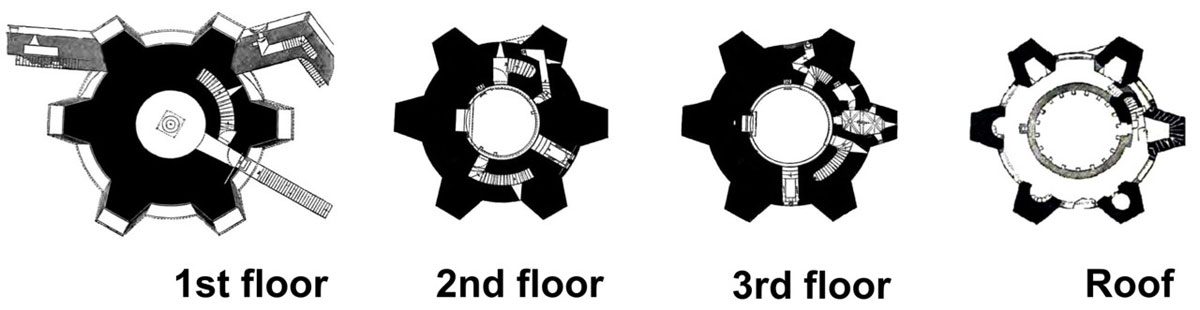

Unraveling aspects of Isabel and Hamelin’s daily lives and connectivity with their social counterparts starts with an examination of the architectural elements of the main part of the home, the keep. The polygonal shape of the tower mirrors those commissioned by King Henry II, Hamelin’s half-brother (see Figures 1 and 2; Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 11; Goodall, 2011, 151).4 This shape is indicative of Hamelin’s desire to show alliance with his half-brother and signal his dedication to England (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 11). Any doubts of allegiance to the Plantagenets were remedied in the chapel just off the third-floor bed chamber (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 12). Placed in the center of the quadripartite ceiling is a silver penny cross surrounded by planta genista (common broom flower), the Plantagenet flower used in the crest of both Geoffrey of Anjou and Henry II. The couple’s desire to demonstrate familial pride and affiliation is exemplified in the shape of the keep and through the ornament in the chapel. Although the couple came to own Conisbrough through Isabel’s de Warenne inheritance, these two elements are telling of an attempt by the couple to celebrate their Plantagenet roots.

Allegiance to Henry II was essential for Hamelin. Born an illegitimate son who was raised in the duchy of Anjou, Hamelin had no money and no great support in England (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 11). Hamelin’s arranged marriage to Isabel gave him connections to a respected family, financial support, and a place in Henry’s court (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 11). The polygonal shape may have been popular in the mid-12th century, but if that style was made fashionable by Henry, Hamelin and Isabel’s adoption of the style made the statement that they were dutifully following leader. The representation of the broom flower in the chapel also signifies that the de Warenne couple believed in Henry’s divine right to rule—in the Conisbrough chapel, support for God’s chosen king is indicated by the inclusion of the family insignia which is presented at the highest point of the space. As Henry was pursuing military advances in France, declarations of fidelity to the crown in the form of design and ornament would have indicated to other nobles where the couple’s loyalty lay (Warren, 2000: 42). Conisbrough Castle is not just a home, but a symbol of political ties, familial power, and wealth. It is for this reason that EH has likely chosen to celebrate the de Warenne residency over others that might have a greater amount of personal notary documentation or archaeological remains.5

With a strong story of English royalty in place, is there a need to recognize other Conisbrough tenants? EH does acknowledge other residents in their guidebook and in a timeline featured in the gallery, but within the keep and bailey spaces only Isabel and Hamelin are recognized. If visitors engage with the keep and bailey prior to seeing the timeline in the gallery, other narratives are seemingly minimal. The guidebook is an excellent resource, but unless purchased in addition to the entry fee, visitors may not have the book in hand throughout the duration of their tour. The guidebook outlines several other residents including: Isabel and Hamelin’s son, William; William’s son, John (7th Earl of Surrey); and John’s son, John (8th Earl of Surrey). After the fall of the de Warenne family in 1347, Conisbrough fell into the hands of the House of York under Edmund of Langley. Edmund was a trusted uncle of King Richard II and was left in charge of the kingdom when Richard II campaigned in Ireland in 1399. In Richard’s absence, another of Edmund’s nephews, Henry Bolingbroke, Duke of Lancaster, took the throne and became the first Lancastrian king. As Edmund acquiesced to the Lancastrian takeover, he was still considered a valuable member of the court. This is especially true after his marriage to Isabella of Castile. Moving forward, Conisbrough was inherited by Edmund and Isabella’s second son, Richard, later called Richard of Conisbrough. After his untimely demise, the castle was left to his second wife, Maud Clifford. Maud was the last to call Conisbrough Castle home.

Because the architecture and the ornament in the keep recall Isabel and Hamelin’s contribution to the site their story is the most predominately featured. Building a story line based on the remains of the site creates a sense of authenticity about Conisbrough’s origins. However, if didactic displays were expanded to include later residents in addition to the de Warenne residency, visitors could consider how Conisbrough was a ‘witness’ to multiple lives and events through the centuries, especially those few ‘big names’ that called Conisbrough Castle home. Despite the later tenants’ recognizability, they are perhaps only displayed in a limited capacity because of the mishaps that befell them. William the 6th Earl of Surrey lost the family lands in Normandy when Philip Augustus captured the duchy under the rule of King John I (1204–05). John the 7th Earl of Surrey is remembered for his ‘aggressive temperament’ and the disputes he had with his neighbors that were ultimately settled by the ruling monarch, Henry III. The last de Warenne resident, John the 8th Earl of Surrey, lost Conisbrough in a dispute with Thomas, Earl of Lancaster. Conisbrough was later regained after the pair made peace, but of course, this renewed ownership came with fees. There was not a de Warenne heir after the 8th Earl’s reign and Conisbrough Castle became the property of the ruling House of York. As stated, Edmund Langley and Isabella of Castille were the next to call Conisbrough Castle home. Their child, Richard of Conisbrough, followed in their stead. However, it is much debated whether Richard was the child of Edmund since Isabella was known for her love affairs. Richard, the last male resident, was beheaded after his participation in the famous Southampton Plot. ‘Mishap’ is an underlying theme for those that followed Isabel and Hamelin de Warenne (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015). The later residents at Conisbrough Castle had less of a ‘fairy tale ending,’ making them less desirable characters in which to focus guests’ attention.

Despite the fantastic stories of these figures, they are only represented in the guidebook and in the gallery timeline. These sources help visitors to imagine later residents’ lives, but they do not convey the same sense of importance at the site as those dedicated to the featured figures, Hamelin and Isabel. While the choice to highlight Isabel and Hamelin was one of convenience because of the form of the keep, the interior ornamentation, and the ‘happily ever after’ ending, the later narratives are indicative of how Yorkshire and Conisbrough’s role in England’s wider history. The complicated histories of the later residents are perhaps convoluted, and even seemingly negative. Regardless of any complication or a lack of a fairytale ending, there is something to be gained from the recollection of the post-Isabel and Hamelin narratives: life is not always a fairytale in a castle. I posit that the trials and tribulations of the later residents might be more relatable to today’s visitors as their hardships with money, society, and in love are something that people of today also face in their own lives. Relatability aside, presenting the longer history of Conisbrough Castle demonstrates to visitors of the site that in many ways, life carries on in much the same way over time: families are made, personal moments shared, and ties are made to greater socio-historical events that are all take place within the same walls. Having discussed all the residents and their current representation at Conisbrough in conjunction with the goals of EH, the next step is to examine the current display methods and consider areas of possible growth.

Presented Pedagogies and Developing New Didactic Displays

Upon arrival at Conisbrough Castle visitors are directed to start their self-guided tour in the bailey, then explore the keep, and lastly enjoy the gallery that empties out into the EH gift shop. EH uses cartoons to create a visual consistency for guests as they move from one space to the next. This final section of this study considers the current forms of engagement and ways in which to improve them based on the concerns of Sheldon, Savage, and Wyeth. Examining the strategies currently being used to tell the story of the featured historical figures Isabel and Hamelin will justify the need for updates, which at EH’s larger sites, have already been put into motion. Touring through the bailey, keep, and gallery as intended by EH, I describe here the benefits and areas of improvement for the current display programming and consider developing new didactic engagements.

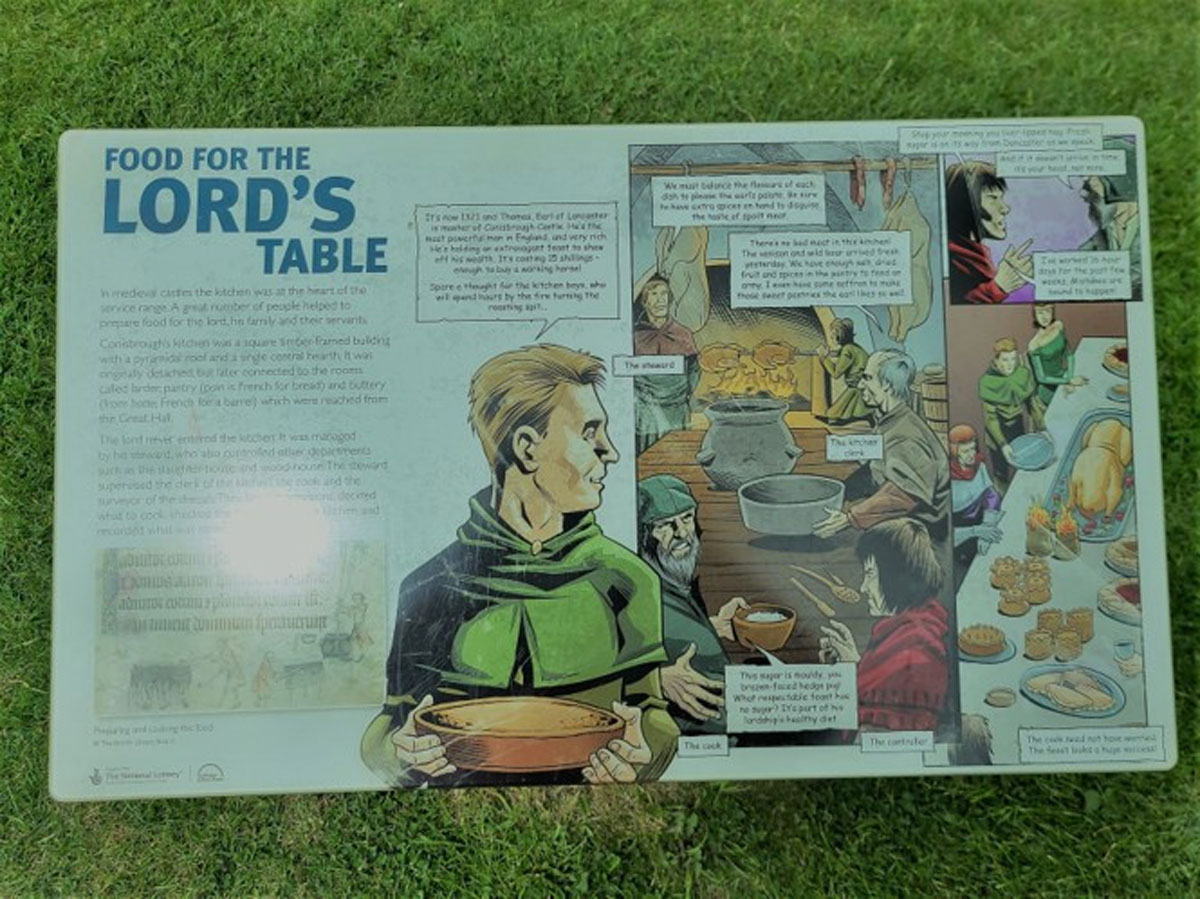

The bailey is treated as the entry point to the castle and as a place for recalling the spaces lost to time. Using a series of illustrated signage boards, EH recalls the lives of those who once walked through the bailey on their way to the kitchens, armory, and servant dormitories. The display boards present several household figures drawn in the style of a graphic novel (Figure 3). While there was initially some commentary that this style may date quickly, visitor feedback is overall quite positive (Davis, 2014: 11–12; Google Reviews for Conisbrough, 2022–2023; Trip Advisor Reviews for Conisbrough, 2022–23).6 I also question the longevity of the graphic novel-style approach, but I think recognizing that this interaction is for a directed audience is key in examining their placement in the keep. As is indicated by Sheldon with his use of PSP gaming consoles, and later by Savage and Wyeth with their videos, fun is a necessity when attempting to keep the attention of a younger viewer. The audience shifts school children to a more diverse age group when the text (which is rather lengthy) is read by the visiting adults, and when adults accompanying their children are pulled into the presented story as the castle ruins are reimagined in their former glory through word and image. As the boards remain undamaged by exposure to the elements and are praised by visitors, this method of engagement and education is a successful means of drawing guests into the castle narrative that is expanded in the keep.

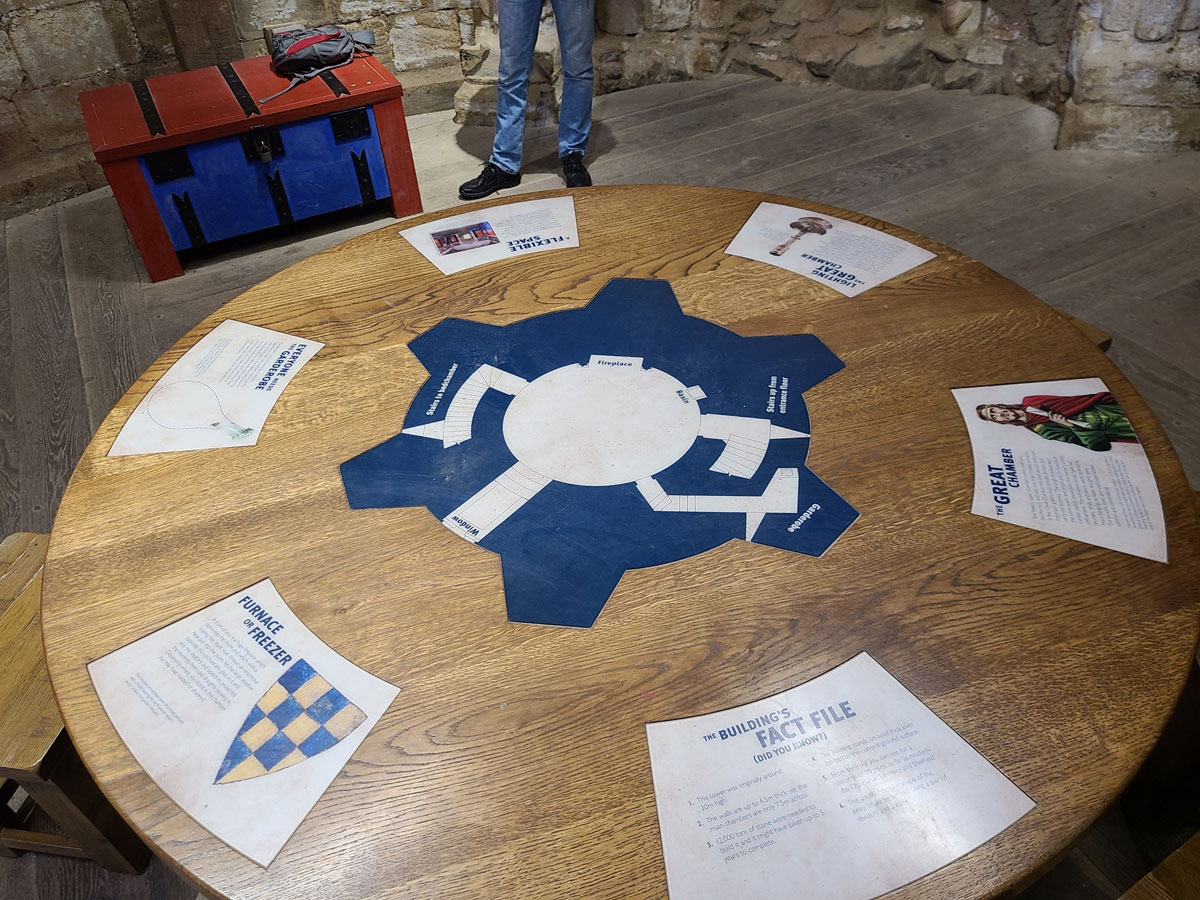

The keep is the main appeal to Conisbrough Castle. Upon climbing the newly constructed stairs, guests enter the first floor of the keep and are greeted by a video projection of a character on the wall opposite the entry. Complementing the style of the story boards in the bailey, the projections on floors one, two, and three represent the de Warenne steward, Lord Hamelin, and Lady Isabel in ascending order (Figures 4, 5, 6). Each projected character introduces themselves to the audience and presents their role in the castle in conjunction with an assumed personality. As the floors of the keep are relatively small, time before or after watching the projections can be used to investigate the special features of the space, including the chapel, the latrine, and the more detailed architectural elements. Activity tables are centrally placed on floors two and three of the keep, each of which is equipped with an inlaid blueprint of that floor and encircled by ‘fun facts’ about the space and people during the de Warenne residency. As these interactive elements are already in place, it would be most cost-effective to enhance the space and progress the castle’s narrative with these pedagogical methodologies.

The video projections align with Savage and Wyeth’s favoring of this media as a means of creating interaction without great alteration to the material surrounds of the keep. Visitor feedback for the projections has been wholly positive (Google Reviews of Conisbrough Castle, 2022–23). During my own visit, I witnessed a range of ages following the character’s story, laughing at the inserted jokes and puns in the characters’ script, and especially with the younger guests, an exchange of comments on the characters’ medieval garb. Each character projection plays on rotation with four-minute intervals, allowing a group of guests to listen in, then explore, and return, should they wish to see the projections a second time. The great benefit to the use of projectors is that they are not only unobtrusive to the space, but that there are many opportunities to share information with guests through this medium. One idea for expanding beyond the Norman narrative is that new characters from later residencies could be introduced. To avoid the possibility of overwhelming guests with too many narratives or too much information, maintaining some pause between showings would be necessary. The current four-minute interval may need to be decreased to a one-minute interval between characters. After a small set of character projections (I propose no more than three) the projections would then revert to the four-minute break so guests that can enjoy exploring the space. Creating two more characters per floor could demonstrate to visitors the evolution of Conisbrough as a home over the centuries and how it was a setting for multiple families’ triumphs and tribulations.

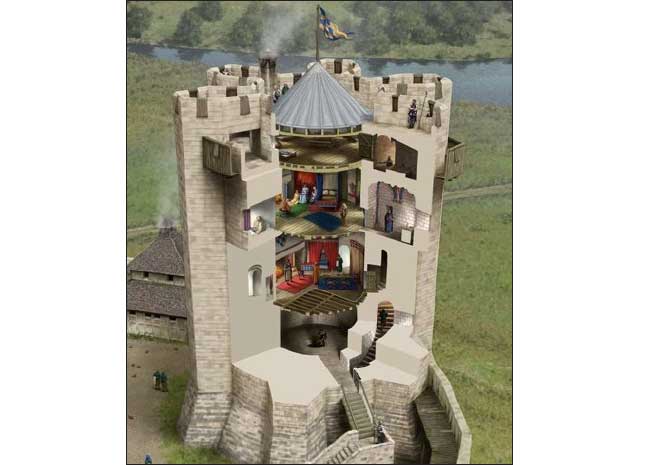

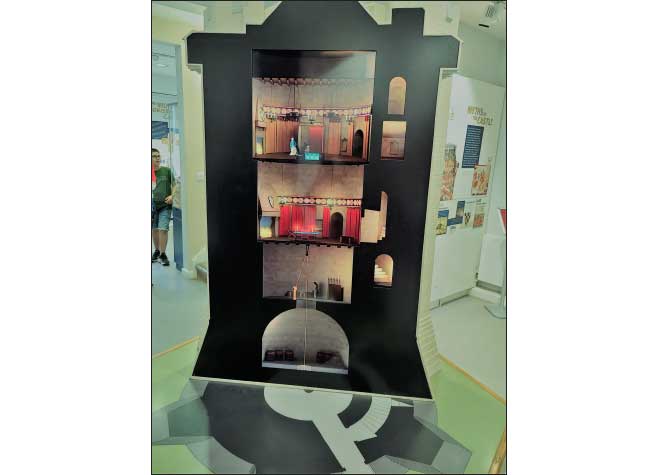

I recommend expanding the narrative of the history of Conisbrough through the recalling of several residents, but having multiple characters on repeat may detract from the experience of enjoying the keep. Another option is to treat the keep itself as a kind of character by projecting medieval household objects that would be found in this space. Because of weathering and animal accessibility, historic or recreated objects cannot be physically displayed in the former domicile. Household objects like furniture, draperies, and refined decorative objects are comparable to the current projected characters’ costumes in that objects in the home are indicative of a resident’s socio-economic standing, their access to the local and non-local markets, and their dependency on everyday necessities. At present, there is no indication of what life was like for the featured historic figures or any other succeeding tenant within the keep space. The only opportunities to envision a furniture-loaded keep are either in a three-dimensional keep model in the gallery space or the replicated illustration in the EH guidebook (see Figures 7 and 8). Both allude to the thick wall hangings, heavy furniture, and refined display objects that would likely have been present at the de Warenne residency. The projector can be used to not only present everyday objects that Isabel and Hamelin would have once kept, but also those from the later residents so their stories can have a greater presence at Conisbrough. Through the in-place projector there are two means of expanding the history of the castle for the audience. It is ultimately up to EH if either figures or objects are the best approach for representing the lesser acknowledged stories at Conisbrough. However, I argue that either or both is better than neither at all if EH strives to more frequently celebrate castles as domestic sites rather than defensive structures.

Should Conisbrough managers choose to focus on the keep and its former objects with their projectors, they can align the new projections with the style of the two-dimensional display boards by using cartoon-style speech bubbles to provide a quick title or descriptor and date of creation for onlookers of the projected objects. Even as few as four objects per interval (one per minute) could introduce the visitor to the kind of wealth and the everyday needs of the residents. A mix of ceramic wares, wooden chests, beds, tapestries, and even jewelry, all of which are recalled in the guidebook, could be presented through a photo-realistic projections to help guests to better visualize what the now empty space looked like for the former residents. In comparison to the suggestion to add new characters, this method of engagements and extending education will allow guests to move more freely after only one character narrative. Furthermore, should the idea of added projection detract from the natural atmosphere of the castle, a QR code could be utilized for a web-based visualization of each floor of the keep.7 With images of the domestic objects either physically located on site or projected on display, guests can better imagine the domestic surroundings of Conisbrough’s former tenants and find connections between Yorkshire of the past and in present day.

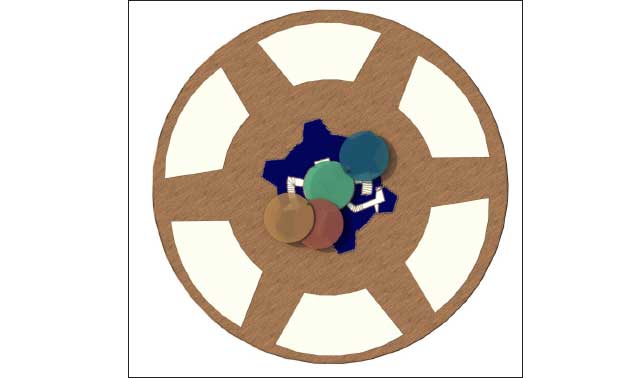

The existing activity tables in the keep can also be further utilized (Figure 9). I propose that over the blueprint map which is central to each tabletop (Figure 10), acrylic roundel slide-outs should be added with various representations of how the room would have looked for different historic times and tenants of the castle. As depicted in Figure 10, each acrylic layer would be approximately between a quarter of an inch and half an inch thick and intended to last through extensive user handling.8 Using something like a shoulder bolt on an outside edge of the acrylic roundels would allow guests to rotate layers in and out. The rotating feature may especially appeal to younger guests that enjoy the tactile satisfaction of ‘fidget toys.’ Appealing to guests first through its physical possibilities, the roundels will then attract through their visual attributes. The acrylic layers can be backed with a solid color (Figure 10) to denote a new time period per layer, or remain clear so that through the ages, more objects are added to the room (Figure 11). Using clear acrylic would add to the viewer experience the idea of layers of recovery in an archaeological excavation, a process certainly celebrated at Conisbrough and by EH. Should the acrylic roundels have backing, text with historic details could be added, summarizing each resident in a few sentences or bullet pointed facts. As is indicated in the provided rendering, an addition such as this would create a tactile feature in the room for those seeking an interactive experience. My proposal for changes is simply theoretical, but in lieu of paper hand-out activities or the introduction of e-games, this option is a one-time investment that will not require reprint or electronic updates and conveniently builds on what is currently in place. As these proposed options utilize interactive systems already at the location, they are perhaps not too far of a reach should EH wish to build on Conisbrough’s narrative in future site updates. Educating through experience and through touch would align Conisbrough Castle with Sheldon’s approach of learning through enjoyable engagements.

Interaction through touch has successfully been implemented at other Yorkshire heritage sites. The aforementioned YAT property, Barley Hall, and the Yorkshire Museum, managed by the Yorkshire Museum Trust (YMT), both initiate learning though tactile experiences. Barley Hall is an authentic medieval domicile like Conisbrough Castle and recalls one of its former residents through a living museum approach. Providing guides in medieval apparel is certainly a part of their programming, but more importantly, Barley Hall allows their visitors to sit in a great hall and touch recreated medieval objects (ceramic vessels, spoons, textiles, and furniture). Visitor feedback praises the ‘real life’ atmosphere and playful spirit of Barley Hall. Commentors claim that ‘Barley Hall is an excellent place if you want to experience how a medieval townhouse would have looked back in the day,’ and that it is a ‘Marvelous place to visit a great example of medieval architecture, and the items on display show the history of the building very well’ (Google Reviews of Barley Hall 2022–23). Imagining the medieval past is made possible through recreation at Barley Hall. The same is true at a neighboring site, the Yorkshire Museum. Although the Yorkshire Museum is not housed within a former medieval domicile, it does recreate the same great hall area that is praised at Barley Hall. Within this recreated great hall space visitors are invited to sit at a long table, touch remade dining objects as at Barley Hall, and all the while, be surrounded by authentic medieval household goods in glass display cases. When visitors are not pretending to feast at a medieval table, there is also an opportunity to play dress-up and move about the medieval wing of the museum in full medieval attire. Guests have commented that ‘The museum has a strong balance of exhibits and treasures with interactive [and] fun… elements that are most engaging for little ones and add to the pleasure of a family visit’ (Google Reviews of the Yorkshire Museum, 2022–23). Conisbrough Castle is unable to create such a setting in the keep because of exposure to animals and climate. This is possible in the gallery space, but doing so does not provide the same effect as Barley Hall of seeing medieval objects in the medieval space. Utilizing the table at Conisbrough as a means of establishing a sense of excitement through touch is, at present, the most unobtrusive and least complicated way of introducing kinesthetic learning while simultaneously increasing visitor awareness to the role of the castle as a home.

Movement, touch, and consistent stylistic elements in the signage aid guests as they move from the keep into the only newly constructed space, the gallery. The gallery space at Conisbrough Castle is relatively small and is shared with a classroom space and the EH gift shop. Directed to enter through one entry point and exit the other, visitors are taken through a chronological history of Conisbrough Castle, its residents, and the archaeological finds uncovered over the years. A timeline that is waist/table-high (eye-level for children) guides visitors around the outside edge of the room, allowing them to bounce back and forth from the more centrally placed displays to the historicized information on the timeline. Among the centrally placed display tables is a three-dimensional recreation of the keep that is represented on page nine of the EH Guidebook as a two-dimensional illustration (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 11; see Figure 8). The three-dimensional model shows each room of the keep complete with animated figures and crackling fireplaces on two-dimensional digital screens. The accompanying signage reads:

This animation shows how the main rooms of the keep may have looked in the late 12th century when Hamelin and Isabel were in residence. The spaces would have been filled with wall hangings and furniture that the lord and lady brought with them as they travelled through their estate, creating a more comfortable home than the cold stone interiors you can visit today. The steward managed the estate throughout the year, and attended to Hamelin and Isabel while they were in Conisbrough. You can meet all three of these people when you visit the keep itself (English Heritage, 2013).

I find both the two and three-dimensional visualizations an excellent means of demonstrating domesticity. The projections in the keep give a sense of human presence in the space, and through this mini model, that idea is repeated with visualized medieval furnishing. This didactic feature, despite not having been based on a specific document or medieval representation of the home, is a convincing aspect for visitors as it helps all to envision what life was like in the keep at Conisbrough. The projected characters in the keep help guests to imagine the people who once called this place home, and within the three-dimensional model in the gallery and the copy in the EH guidebook, the former residents’ story is enhanced by shedding light on the kind of objects they surrounded themselves with in their own home.

As was the case with Wyeth and Savage’s case studies, the representation of women at Conisbrough needs reevaluation. Above the two-foot stretch of the timeline in the gallery marking the residency of Maud Clifford are caricatures of three prominent female residents: Isabel de Warenne (1137–1203), Isabella of Castille (1355–1392), and Maud Clifford (1389–1446) (Figure 12). The lives of these ladies are associated with their marriage marketability, scandal, and the idea that certain facets of everyday life were ‘dull.’ These women’s narratives are certainly linked to their role as wife and mother, but women were so much more than these titles in the Middle Ages. Conisbrough and the de Warenne name came from Isabel’s family, not the Plantagenet line from which Hamelin descended (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 27). Even though Hamelin was the head of the family, his power was only achieved through his marriage, generously arranged by King Henry II (Brindle and Roznowska-Sadraei, 2015: 27). Isabella of Castile was known for her torrid affairs, but again, her marriage to Edmund, Duke of York, was arranged to bolster his status should he become king (Pugh, 1998: 90–91). Maud was the second wife of Richard of Conisbrough, and their marriage was childless. Upon his demise, she remained at Conisbrough Castle. She hosted relatives, supported local religious institutions, and bequeathed generously to kin (Surtees Society, 1855: 123). Understandably, there is limited space in which to recall so many narratives and ideas, but doing greater justice to the female players at this monumental site would surely enhance the visitor understanding of life at Conisbrough Castle across time. Such an expansion and clarification could also help visitors learn to celebrate female historical figures versus make light of them. Increasing representations of women aligns with the Savage and Wyeth’s goals for EH updates, but at Conisbrough the concern is perhaps for the type of representation versus a lack thereof. Using the existing tabletop spaces and projections in the keep, and even by simply updating the text on the gallery signage, the women of Conisbrough and their contributions to their home and their broader society can be better recognized.

The ideas I have presented here for expanding visitor engagement are simply that—just ideas. The current displays do meet the goals set out in EH’s mission statement, and for that, I do commend EH for having such a complete program. The on-site managers at Conisbrough Castle are presently addressing the concept of the castle as a domicile, which does align with the goals set out by Savage and Wyeth. While succeeding in recalling the function of the keep as something other than a defensive structure, there is room to consider controversial narratives by further utilizing the existing projectors, tables, and signage. Sheldon’s required fun is expressed in visitor reviews, and because of the possibilities in the keep’s projectors and table toppers, there is an opportunity for increasing visitor engagement should EH so choose. Conisbrough Castle has a long history of fascinating residents, making the options for development endless. As EH continues to consider means of enjoyable learning while combating the challenges of conveying the histories of their sites, it is my sincerest hope that Conisbrough Castle is recognized for having addressed the needs of the space and expectations of the incoming guests.

Conclusion

Towering above the homes of suburban Doncaster, Conisbrough Castle is a reminder to those living in and touring the area that the medieval past is accessible through surviving sites. For its visitors, EH has recalled a story of Noman-era politics, architectural and ornamental symbolism, and the successes of its former residents, Isabel and Hamelin de Warenne. The presented de Warenne narrative meets the goals set out in the EH mission statement of educating guests on medieval events and people of the site through fun activities and experiences, which is accomplished through a series of unified informatics. The audience is visually guided from the bailey to the keep and then the gallery through the consistent use of graphic novel-style cartoons, which, although they are aimed at younger visitors, present accurate historical content. The de Warenne residency illustrates the relationship between a medieval home and wider society through form and ornament. It is the goal of this study to engage with the works of Sheldon, Wyeth, and Savage who all wish to see updates in the didactic displays at the many EH properties that expand beyond the Norman narrative, recognize the role of women, and recall the domestic nature the castle all while providing entertainment for visitors (Sheldon, 2011; Savage and Wyeth, 2020). Conisbrough Castle is a prime example of a heritage site that meets the goals of their managing group but has the potential for offering more through their existing programming.

My presented ideas for reinvigorating the current display methodologies, particularly the projector and the activity tables in the keep, are intended to aid Conisbrough in modernizing and keeping up with those updates being implemented at EH’s larger sites. The projector in Conisbrough’s keep opens the door to countless opportunities for displaying the medieval past in a space that cannot host historical objects. The current array of characters has been well-received by visitors, and I have no doubt that additional figures or objects to the presentation will add to the success of this means of pedagogy. Other heritage sites have implemented teaching through touch. Conisbrough can deliver this mode of engagement should EH choose to do so. High praise has been given to other Yorkshire sites that use more than one educational approach, and as an educator, I can attest that using a variety of approaches can lead to a greater understanding of the presented materials. EH’s Conisbrough Castle certainly appeals to a diverse audience but assuring the absorption of the presented information is more likely through variety.

Conisbrough Castle is just one of EH’s many heritage sites. As keepers of history, we are charged with providing a reason for the public to visit historic sites not only for a better understanding of the past, but also as a form of entertainment. I commend EH for their continued work on pedagogical engagements in fun and interactive ways. I hope that as they continue to evaluate their sites, Conisbrough is recognized for all its potential in recalling many residents’ former lives that were once witnessed within the walls of this former home.

Notes

- This study complements the ongoing research (at the time of writing) by EH regarding castles as domestics sites, women and their roles in these spaces, and how to create new or improved visitor engagement. The proposed ideas are therefore not associated with budgetary concerns, but with related ideas about visitor education and entertainment. [^]

- English Heritage 2012 If These Walls Could Talk [video], available at: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Byr1bOiq3Mo. [Last Accessed 30 May 2022]. I have found no visitor commentary on the use of the PSP, and at present, Wroxeter is closed again to update their programming. I am unsure how long the PSP play system was in use and if the goal is to bring it back into the on-site program after EH completes their current round of updates. [^]

- The Bodiam Debate considers whether the castle is best described as a defense, a home, or both. [^]

- Henry II used similar polygonal shapes at Odiham in Hampshire, Chilham in Kent, Tickhill in South Yorkshire, and Orford in Suffolk. [^]

- Isabel and Hamelin resided primarily at Lewes, but the reconstruction of Conisbrough stretched over ten years, and Hamelin was thought to be active in the design process which would have required him being on site. It is also documented that King John visited in 1201. Although not their main home, Conisbrough Castle was lived in by the couple and even used to host major political figures. [^]

- Davis notes in his critical review of Conisbrough that even at the installation of these images in 2013, this style of art was “dated” and would have a potentially short life at the site as the younger visitors they were intended to appeal to were likely more in-tune with new cartoon and animation styles. Commentary on Google by visitors note, ‘Very good, love the graphic novel style information panels. The whole story is there for nerds like me to read but the “comic strip” versions telling the story in the words of the castle inhabitants is very well done. A good couple of hours to see it all. Nice picnic area too.’ [^]

- I am supportive of technology-based informatics, but it should be noted that if you are a non-UK visitor to Conisbrough, then Wi-Fi will be necessary for users to access the information, which based on my experience, it is not currently offered to guests. Because of this, I hesitate to commit to a solely cellular-based source of information. Also, because not everyone is able to use mobile devices with ease, especially many of the older visitors to Conisbrough, this is potentially an inaccessible option for relaying information. If the aim is to educate a diverse audience, then it should be guaranteed that everyone has the option to view the content. [^]

- With the help of Whitney McMakin, a design consultant and founder of ISCO LLC, the concept of the swing-out elements for the tabletop installation is visually rendered and imagined. McMakin did visit Conisbrough with me in 2022, allowing her to best gage the effects of moveable pieces for the existing furniture and for the space (using nothing that would swing out beyond the scope of the table and prevent visitor movement). [^]

Competing Interests

The author has no competing interests to declare.

References

Ashworth, GJ, Graham B and Tunbridge JE 2007 Pluralising Pasts: Heritage, Identity and Place in Multicultural Societies. London: Pluto Press.

Boniface, P 1995 Managing Quality Cultural Tourism. London: Routledge.

Brindle, S and Roznowska-Sadraei, A 2015 Conisbrough Castle. London: English Heritage.

Davis, P 2014 Shining Light onto Conisbrough Castle. Castle Studies Group Bulletin 18 (September 2014): 11–12.

English Heritage 2004 Vision and Values. Swindon & London: English Heritage. https://www.english-heritage.org.uk/about-us/our-values/ [Last Accessed 27 March 2023].

English Heritage 2012 If These Walls Could Talk [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=Byr1bOiq3Mo. [Last Accessed 30 May 2022].

English Heritage 2013 Signage located in the Gallery at Conisbrough Castle [Accessed by Author in 2022].

English Heritage 2018a A Mini Guide to Medieval Castles [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=RXXDThkJ3Ew. [Last Accessed 30 May 2022].

English Heritage 2018b How To Take A Medieval Castle [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=xNeNPk4D_Ng. [Last Accessed 30 May 2022].

English Heritage 2018c What Was Life Like? Episode 6: Castles—Meet a Medieval Noblewoman [video]. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=1k-LhWB4QaA [Last Accessed 27 March 2023].

Goodall, J 2011. The English Castle. London: Paul Mellon Centre.

Google Reviews of Barley Hall 2022–2023. https://www.google.com/search?q=reviews+on+barley+hall+york&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS777US777&oq=reviews+on+Barley+Hall&aqs=chrome.3.69i57j33i160i395l2j33i22i29i30.6811j1j4&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8#ip=1 [Last Accessed 27 March 2023].

Google Reviews of Conisbrough Castle 2022–2023. https://www.google.com.my/travel/entity/key/ChYIgsmbgMudqc2AARoJL20vMDE0MmNzEAQ/reviews?ts=CAESABoECgIaACoECgAaAA&ved=0CAAQ5JsGahcKEwi4uvPeooX-AhUAAAAAHQAAAAAQAw [Last Accessed 27 March 2023].

Google Reviews of The Yorkshire Museum 2022–2023. https://www.google.com/search?q=reviews+on+the+yorkshire+museum&rlz=1C1CHBF_enUS777US777&oq=reviews+on+the+yorkshire+museum&aqs=chrome..69i57j33i160.7113j1j7&sourceid=chrome&ie=UTF-8 [Last Accessed 27 March 2023].

Johnson, S 1984 Conisbrough Castle, South Yorkshire. London: English Heritage.

Platt, C 2007. Revisionism in Castle Studies: A Caution. Medieval Archaeology, 51 (1), 83–102. DOI: http://doi.org/10.1179/174581707x224679

Pugh, TB 1998 Henry V and the Southampton Plot of 1415. Southampton: Southampton University Press.

Savage, J and Wyeth W 2020 Exploring Unique Challenges of Presenting English Heritage’s Castles to a Contemporary Audience. Defensive Architecture of the Mediterranean, 11: 993–998. DOI: http://doi.org/10.4995/FORTMED2020.2020.11421

Sheldon, D 2011 If These Walls Could Talk: A Case Study of Playing Your Way Through a Project. In: Beale, K (ed.) Museums at Play. Edinburgh: Museums Etc. Ltd. pp. 326–337.

Surtees Society 1855 Testamenta Eboracensia: A Selection of the Wills from the Registry at York, Parts 1–3 of Volume 30. Durham: George Andrews.

Trip Advisor Reviews of Conisbrough Castle 2022–2023. https://www.tripadvisor.com/Attraction_Review-g1799856-d8457955-Reviews-Conisbrough_Castle-Conisbrough_Doncaster_South_Yorkshire_England.html [Last Accessed: 27 March 2023].

Tuckley, C and Di Mascio, D 2021 Barley Hall: New Narratives for an Old Building. In: Di Mascio (ed.) Envisioning Architectural Narratives. Huddersfield: University of Huddersfield. pp. 556–566.

Warren, WL 2000 Henry II. New Haven: Yale University Press.